My interview for an editing job at Beijing Review was short and simple. The HR manager wanted to make sure I understood the job would be very boring and that I would be ok with that. Boring meant a 40-hour work week with about eight hours of actual work. I'd be expected to "polish" about three stories each week. Polishing is distinct from editing because it's strictly cosmetic, with no fact checking or anything else that might cause my co-workers to do more work.

I inherited the job from a former CBC reporter who, like me, had bounced around state media jobs in Beijing for a couple of years. State-controlled Chinese media have been making a major international push in recent years, hiring at a time when most Western media outlets were contracting in the wake of the financial crisis. Most of the jobs pay around 12,000 renminbi per month -- a little less than $2,000. Not a lot given Beijing's rapidly rising living costs, but still about three times what our Chinese colleagues make -- though they also get generous pensions and other benefits, including, bizarrely, regular gifts of soap and toilet paper.

The foreign journalists hired to work in government media are almost exclusively copy editors, simply there to clean up the English (or French or any of dozens of other languages). They are occasionally allowed to do some actual reporting and foreigners host many of the programs at broadcast outlets like China Central Television and China Radio International, though usually with a Chinese co-host who doubles as a babysitter. Beijing Review is one of the smaller publications and we usually had three or four foreign copy editors on staff.

Beijing Review is a weekly news magazine published by the Chinese government and it is not available in newsstands. Its main circulation is through government institutions such as universities and foreign embassies and consulates. Shortly after I started, the editor-in-chief told me they all knew no one read the magazine and that they were just there to collect a paycheque. The editor-in-chief is not a journalist. He is a bureaucrat. He isn't producing a magazine. He is filing paperwork. He isn't judged by readers because there aren't any. He is judged by his superiors at the State Administration of Radio Film and Television, the government body responsible for running China's media apparatus. Because the government sees foreign language publications as a projection of China's "soft power," the Ministry of Foreign Affairs also watches over the editor-in-chief of Beijing Review. The priority of these bureaucrats is not to produce a functional, credible news magazine. It is to produce something that approximates a news magazine. The imperative is to make it look like Time or Newsweek and give China the appearance of a modern developed nation with a media presence commensurate with its growing status.

The biggest challenge in polishing the stories at Beijing Review was deciding what to do about all the plagiarism. Chinese practice allows the use of whole paragraphs without attribution as long as one doesn't plagiarize the entire article. So the writers at Beijing Review usually just found a few articles from foreign publications, selected their favorite paragraphs and then cut, pasted and arranged them into a "new" article. It was always easy to tell when this happened because the articles contained paragraphs in a variety of different font sizes and styles and often still had the hyperlinks from the original articles embedded in the text. The writers also broke up paragraphs of immaculate English with transitional paragraphs of heavy Chinglish, making it even more obvious that the "writer" hadn't written much at all.

The stories were boring because for the most part the writers were bored with writing them. Like the editor-in-chief, they were just filing paperwork. Most journalists are news junkies. The staffers at Beijing Review were distinctly uninterested in the news. They did the minimum research necessary to get through their stories. They were allowed to get by without doing any original reporting -- and unlikely to be rewarded if they did, so most didn't. It was easy to tell when someone was doing actual reporting because they would come to us with lists of questions they planned to ask and wanted to check for grammar first. On average this happened maybe once a month. Phones in the Beijing Review news offices remained almost completely silent.

When writers had met their weekly requirements they usually watched videos on Youku, China's Youtube knockoff. In the afternoons most of them slept. One afternoon I was the only person awake in a room of about a dozen people and the editor-in-chief walked in. He sounded surprised and almost concerned, as if something were wrong, when he asked, "Why aren't you sleeping?"

Bias and bear bile

The magazine did run some stories that weren't overt propaganda. But it also ran articles openly discussing problems in Chinese society, such as one on a failed government housing project in Beijing and another on a pharmaceutical company that had an IPO backfire when potential investors learned the company's primary product was a traditional medicine made from bear bile. Much of what appeared to me as propaganda was simply the result of the cultural biases of the writers, rather than something directed from above. I found many of the articles to be biased for the same reason my co-workers found anti-Chinese bias in American media or American readers find bias in Al Jazeera. In one article about disputed islands in the South China Sea, the writer claimed other countries recognized China's claims. I could find no evidence to support this and reported the issue to the editor of the world desk. When the writer found out I suggested removing the sentence, the whole newsroom went into an uproar. My co-workers felt I was rejecting China's entire claim to the islands by doubting whether other countries recognized China's claim. Though I was never able to make the distinction clear to most of my coworkers, I did make my point to the world editor, who removed the sentence in question from the article.

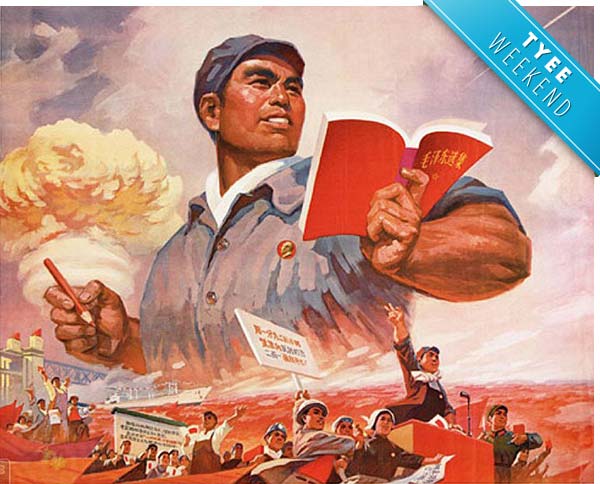

The boredom and mindless insistence on mediocrity were broken up by sublimely surreal moments that could only happen in China. In March the magazine ran a barely disguised infomercial for the state-run China National Convention Center as a news item in the business section. The cover story for that issue was about Lei Feng, a Cultural Revolution icon held up as a paragon of Communist virtue. The strangeness extended to the physical environment. The cleaning staff were forbidden to enter the offices because at some point something went missing and the cleaners got blamed. The offices were a disaster, but the hallways and bathrooms sparkled. Someone somewhere decided they didn't like the concrete overhang on a building that was being renovated. So for a few days workers stood on top of the overhang they had just built and happily jack-hammered it off.

The great news bureaucracy

The people who work for government media in China are not journalists, and the vast majority aren't dedicated propagandists. They're actually a lot like the people you might find working for the government in other parts of the world. They have all the drive and passion for their work as that shown by the clerk I encountered when I last visited the DMV. They want a steady paycheque and decent benefits without fear of a layoff -- China's "Iron Rice Bowl." They want pensions, not Pulitzers.

The question is where is Chinese media headed? People here talk about "crossing the river by feeling the stones," meaning to take things slowly, one step at a time. The economic reforms that began in the late '70s took a couple of decades to pick up steam. Those reforms took off when private enterprise became a stronger engine for economic growth. In stark contrast to the manufacturing sector, Chinese media continues to languish in government shackles and it won't be crossing the river to full Western-style press freedom and market competition anytime soon. But its future success will depend on how many steps in that direction it is allowed to take. ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: