- The Fog of War: Censorship of Canada's Media in World War Two

- Douglas & McIntyre (2011)

Think about Canada in the Second World War, and you likely think about overseas battles and campaigns: Hong Kong, Dieppe and the liberation of the Netherlands. Think about Canada at home during that war, and you likely won't think about much: Conscription, the deportation of Japanese Canadians from B.C., convoys from Halifax.

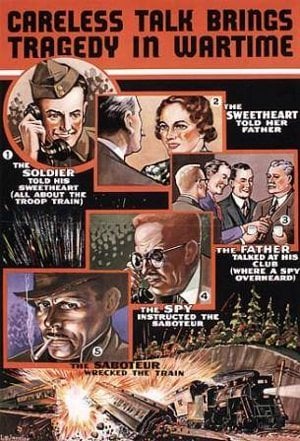

That's because the propagandists in both wars emphasized heroic combat (with the messy bits airbrushed out), and the censors made sure that Canadians at home heard as little as possible that might be of value to the enemy. But they also made sure we wouldn't hear anything that would discourage young men and women from enlisting.

As a result, news of many important events was suppressed. After the war, those events seemed too stale to make public, or to remember. So one of the surprises of this excellent book is that, between 1939 and 1945, Canada was fighting a deadly and complex struggle here at home.

Another surprise is that censorship in the Second World War was also a complex struggle: The censors (themselves professional journalists) had to deal with a military that wanted to censor everything, politicians trying to stay in office and news media that wanted to cooperate but often considered censorship absurd and pointless.

In the First World War, Canadian censorship had gone overboard, even banning recordings of Deutschland Über Alles. Mark Bourrie argues that when war broke out again in September 1939, prime minister Mackenzie King had two key goals for news censorship: To keep military and economic intelligence out of the hands of the Axis and to keep civilian morale from breaking down.

These goals were hard to achieve. The Americans, neutral for two years, freely reported information that Canada wanted suppressed. After the fall of France, the puppet Vichy regime sent diplomats to Ottawa who kept the Nazis informed. Much of the Quebec media strongly supported Vichy, while opposing Canada's role in the war.

Bourrie reminds us that we were losing for the first three years. The Nazis and then the Japanese triumphed again and again. So the censors had to ensure that the war news scared Canadians into accepting rationing and other measures, without scaring them into despair.

He makes it clear that the censors' worst enemies were not the journalists but the military -- especially the Navy, which didn't want to release any news at all. Most of the Canadian media, however, tried hard to cooperate. But what was the point of silencing a CBC or Montreal Gazette report if the locals could tune in to an American station carrying the same story?

Life for the censors was complicated still further by some of Quebec's francophone media. Important papers like Le Devoir were openly hostile to the war and friendly to fascism and anti-Semitism. While Mackenzie King had promptly shut down communist papers across the country, he let Quebec fascists print almost anything they pleased. (Montreal Mayor Camillien Houde was thrown in jail for his political statements; that ensured him re-election after the war.)

How could a national government, fighting for its democratic life, allow these wannabe quislings to support the enemy and subvert the war effort? Mackenzie King understood Canada's politics better than anyone, and he knew that a crackdown on Quebec's fascist intellectuals would only make matters worse.

Bourrie's book is valuable for such insights, and his description of wartime Quebec helps to explain postwar separatism. Ironically, the right-wing nationalism of the 1940s turned into the left-wing social democracy that first inspired the Parti Québécois and then handed Quebec to the New Democrats.

The censored war at home

Bourrie also describes some astonishing events in wartime Canada that I had known little or nothing about. For example, Nazi U-boats attacked ships anchored off Newfoundland's Bell Island and its iron mines -- just a few minutes' drive from St. John's. The Battle of the St. Lawrence was a grim and bloody struggle between the Canadian and German navies. People living on the shore could watch freighters being sunk and U-boats pursued -- but they wouldn't read anything about it in their papers.

Nor did they read much about German espionage. One spy, dropped off by a U-boat, was almost immediately identified by a 14-year-old hotel clerk: The spy was using obsolete Canadian cash and smoking German cigarettes. The RCMP tried to use him as a double agent, but so many American news sources spilled the beans that the Germans must have known; the spy was kept in jail and sent home after the war. He even got back the $9,000 he'd arrived with.

Another spy, better funded with American $50 bills, headed straight for Ottawa, where he lived in a hotel for two years doing absolutely no spying. When he turned himself in, the censors kept the story out of the press, though it would not have compromised military security.

Obeying a whim of Winston Churchill's, Canada shackled some German prisoners of war; this led to a battle between hundreds of PoWs and Canadian militia in a camp at Bowmanville, Ontario. It was an extraordinary and embarrassing incident, and the censors clamped down hard on it.

In Western Canada, censorship silenced most reports of Japan's "balloon bombs." Japanese scientists had discovered the jet stream before the war. The military exploited it by building thousands of balloons, armed with incendiaries and bombs, and launching them against the West Coast.

The intent was to set fire to Canadian and American forests, but the censors were not about to let the Japanese know how well they were doing. (Not well at all, though a balloon bomb killed a pregnant Oregon woman and five children on a Sunday school picnic.)

B.C.'s zombie war

With the collapse of Germany, Canada's attention swung to the Pacific and the impending invasion of Japan. But this phase of the war would involve the "zombies" -- Canadian draftees who had been conscripted on the promise they would serve only in Canada.

Despised by volunteers and civilians alike, the zombies were shocked to learn they would be shipped to the Pacific. For a few anxious weeks in 1945, military camps in Abbotsford, Vernon and Terrace teetered on the edge of something like a civil war between zombies and volunteers, with both sides armed and trained for battle. In the end, it was a mere mutiny, and the Canadian public learned almost nothing about it until well after the war.

Bourrie's best chapter deals with Tommy Shoyama. A bright young man with a new BA in economics from UBC, Shoyama in 1938 found himself editing the New Canadian, an English-language paper for the Japanese community in B.C. After Pearl Harbor, the RCMP shut down three Japanese-language papers, leaving Shoyama as de facto spokesperson for thousands of Japanese Canadians who were being uprooted and scattered across Canada.

Shoyama himself ended up in Kaslo, still publishing his paper. The censors actually supported him, though they sometimes fought with him over particular stories (and about Japanese-language ads and articles they couldn't read). When Japanese Canadians were finally allowed to enlist, Shoyama was one of the first to join, serving in intelligence as a translator.

After the war, Shoyama went to work for Tommy Douglas in Saskatchewan, and eventually became deputy minister of finance in Ottawa under John Turner, Donald Macdonald and Jean Chrétien.

Has anything changed?

Bourrie's book of course raises questions about the present relations between government, military and media. The military are still reluctant to release any information at all; the government wants politically useful reports; the media struggle between getting stories out and supporting the troops.

Issues weren't clear-cut in the Second World War, and they still aren't. Lacking a censorship system to keep diplomat Richard Colvin out of the media, the Harper government had to resort to Peter MacKay's abuse and insults to try to discredit him. But the principle was the same as in the Bowmanville PoW battle and the zombie mutinies: protect the government and the military.

If the media in the Second World War were trying to do their bit, today's media don't want to seem disloyal either. But it's complicated -- Quebecers aren't the only ones objecting to our involvement in Afghanistan, and the present war is no existential threat to Canada.

If today's military reporting isn't transparent, it's at least porous. Imagine today's online technology in the 1940s, with the zombies in Terrace tweeting to the world about their grievances and Tommy Shoyama blogging about the injustice suffered by the Japanese Canadians. Imagine Ottawa trying to suppress news of the Battle of the St. Lawrence while people onshore were taking photos on their smartphones and uploading them to Facebook.

We see the equivalent in today's conflicts: digital snapshots of Abu Ghraib, diplomatic secrets released by Wikileaks, video clips from Tahrir Square and Occupy Wall Street. It's still possible to shut down an unwelcome story, but it's a lot harder than it used to be.

Mark Bourrie has given us a useful perspective on persisting issues of media freedom, as well as on how Canada fought on the home front -- with consequences that shaped the last 70 years.

[Check out more Tyee Rights and Justice reporting, here.] ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: