Oh the roller coaster of addiction! Lindsay Lohan, after several stints in rehab and jail, has just failed one of her daily drug tests, and could now face legal punishment. She says addiction is a serious disease, but she's taking responsibility and will face whatever consequences.

What's that, you say? You don't care? You don't even know her?

Well, that's partly true. You might have celebrity fatigue or annoyance. You might reject the systems that create it: capitalism, big media, consumerism, Americanism. You might be secretly resentful and jealous. But it's pretty unlikely you don't know who "Lindsay" or "LiLo" is, and don't actually care at all. In fact, it might actually be culturally, psychologically and anthropologically next to impossible to not care. Even men, more than ever, are tuning in to celebrity gossip (the Tiger Woods saga migrated male sports audiences to the tabloids, the new, so-called poparazzi). The questions are: why do we care, and what are we are gonna do about it?

So says a new documentary by... a celebrity.

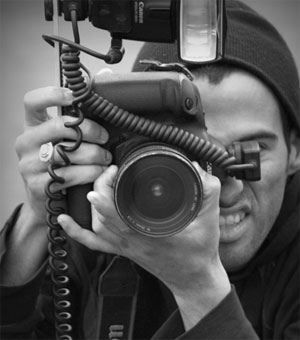

In Teenage Paparazzo, Adrian Grenier (star of HBO's Entourage) gets blinded by the flash of a 14 year-old photographer, and decides to turn the camera on him. What on earth is going on that a pre-pubescent kid is out in the middle of the night stalking then blinding celebrities in order to sell photos to a hungry audience? Grenier wonders.

Grenier follows Austin Visschedyk for two years, during which time, Grenier's lens inadvertently makes Visschedyk into a minor celebrity and a major brat, both of which the two of them deal with by the end.

Jet-fueled gossip

Just as interesting as the actual story are the people Grenier interviews to explain the phenomenon, beginning with James Hosney, a film historian at the American Film Institute. Hosney says that this type of celebrity and the paparazzi that follows and fuels it is very recent. Under the studio system, the studio manufactured stars and had a heavy hand in any information released about their personal lives. "You didn't know anything about them other than what the studio wanted you to know," he tells Grenier.

But now, with the Internet, someone simply says something, and it's true, or at least known by millions. And audiences, of course, tend to gravitate to stories about celebrities' personal lives, rosy or not, and spontaneous, real life shots, not stand-and-smile shots from premiers and movie promo packs.

Perez Hilton, one of the biggest exploiters of celebrity Internet gossip, says in the film, he doesn't "make things up knowingly, but having strong opinions is perfectly acceptable." (And if you've been to his site, the word "opinion" is easily interchangeable with supposed "fact.") But Hilton kind of shrugs and smiles, and says that while not everyone agrees with what he does, he gets up to 10 million unique visitors a day.

The other reason for increased fame of a few, and the increased sizes of the audiences that follow them, is bigger big media. Alec Baldwin wryly explains what he infamously experienced first hand a couple of years ago when he was doing publicity for a movie, and landed in the tabloids. "So you go to work at a studio, which... has a TV arm and a movie arm... While you're making a movie... they want you to go do an interview with them, so they're going to double dip you. We're going to make money off you twice: we're gonna sell tickets to the movie you're in, then we're gonna put you on a TV show to talk about the movie, then we're gonna sell commercials of you talking about the movie, also to make money. And down the hall, there's a [gossip publication] arm that's trying to bury you. So when I did The Departed for Warner Brothers, [the gossip publication] was shoving it up my ass one brick at a time."

But it's more than big media's machinations and money grubbing that make celebrities big. People have to want to see and read about TMZ shoving a brick up Alec Baldwin's you-know-what. Baldwin's tirade at his daughter must have resonated with people for psychological and anthropological reasons.

Why you can't look away

Even if we don't think we care and don't want to care, "some part of us... and that's not the conscious part of us, it's the deep-rooted part of us" pays attention, says Jake Halpern, author of Fame Junkies, who's also featured in the documentary. "I think it's because human beings since time immemorial have benefited from watching powerful people, and that's now hard-wired into our brains."

He cites a recent study out of Duke University with monkeys. "What they found is that these monkeys will actually pass up the opportunity for food, they will go hungry, in order to stare at pictures of the dominant monkeys in their troupe. The only other pictures they gave up food to look at were close up shots of the hind quarters of females."

He adds, "The thinking is that nowadays... that instinct has just kind of gone awry."

But Grenier thinks it's too easy to reduce this to monkey business. Halpern continues by explaining what psychologists call parasocial relationships, which are the "weird, one-way relationships where we don't actually know the people on TV but we think we do." Our brains have the same response to them as to people we actually know.

He says research that shows people have fewer family dinners together, join fewer clubs and have fewer picnics. And more people than ever live alone. "We're lonely... but what we do have is these fake relationships with people we think we know from TV and the movies. And magazines like Us Weekly play right into that. It's all first name: it's all Brad and Angelina and Tom. And these people, they're just like us... it makes us feel that we're part of something. But of course, we're not. We're not part of it."

The editors at one gossip magazine talk to Grenier about how they consciously pick photos where the celebrity is looking right into the camera (at "us") in a casual way as if they know us. So that we feel like we're friends.

But in fact these parasocial relationships make us even lonelier. While we put out, while we feel like we know them, we don't get anything back.

"There's a piece of this that's serious celebrity envy," says Thomas de Zengotita, a professor of media studies at NYU and author of Mediated.

"In this society, if you're not famous, there's a certain sense, a certain very real sense in which you don't exist."

He then compares the kind of attention we give celebrities to a kind of emotional market transaction. "Even mammals, puppies, like attention. But only humans need acknowledgement. They need to be recognized. And this is fundamental to human nature, to the human condition."

A star in your own tribe

He says when we lived in tribes, in small groups, everyone knew everyone. And that meant everyone got acknowledgement and was famous.

"You have to think of the evolution and development of media of all kinds in all societies as taking the fame and the acknowledgement that used to be everybody's, and somehow reassigning it to only a few people. And there's a fundamental sort of robbery that goes on."

So celebrities are taking the attention that we and our friends and families need, and leaving us starving and lonely.

But there is still a social role that celebrity plays, according to Henry Jenkins, a professor of media studies at MIT, as the fodder for gossip. "As we move from a society of small towns where people gossiped about the town drunk, to the era of the Internet, we can't choose to talk about our aunt or uncle or the guy down the street because we don't share that in common. We only share [celebrities] in common."

A celebrity's job is to be the subject of gossip. "When we gossip about someone, the person we're talking about is actually much less important than the exchange that happens between us. We're using that other person -- the celebrity, the town whore, whatever -- as a vehicle to share values with each other and sort through the issues that matter."

The celebrity stories that become the most popular, that stick, are the ones that give us the material to talk about something that matters to us at that particular time, "that speaks to the core conflicts the culture is going through," he says.

So back to Lindsay, and the fact that her story is at or near the top of most tabs this week. When I mentioned the newest installment in the saga to people, some started talking about how difficult addiction is. A few speculated that it's brought on by loneliness and stress. A few told their own stories of addiction and how they did or didn't manage to kick it. But more have talked about the consequences of over-ambitious, over-involved parenting, of trying to make your kid live out your dreams, of taking from them instead of giving. A few have told stories about a kid they know with a stage (or hockey) parent where things are ugly.

There's value in that discussion. We're talking about aspects of Lindsay's story that matter to us, that resonate with our experiences, or that help us think through current issues in our lives, that might even lead us to take action, that make meaning, that create community.

So in the end, we're using celebrity-based gossip to create small connections between real people. And those conversations, ironically, are a small antidote to the very lonely and disconnected world that celebrity culture has a big hand in creating.

However, to really solve the problem, to make things real, Grenier, who's still at work shooting Entourage, thinks we have to turn off the camera. ![]()

Read more: Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: