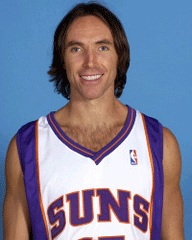

Throughout his unlikely rise to NBA stardom, Steve Nash has always downplayed his achievements. Even after being named the NBA's Most Valuable Player in back-to-back seasons -- a feat accomplished by only eight other players in league history -- the Victoria native seemed pleased yet overwhelmed. "I have to admit it's a little bit uncomfortable to be singled out amongst all these great players two years in a row," said Nash at a news conference after winning the award. "I have to pinch myself, I can't believe that I'm standing here today. I couldn't believe it last year."

He then added jokingly, "But I'm not gonna give it back."

No matter what Nash himself might say, he is entirely deserving of all the accolades. And while many people say it's amazing that the NBA's best player is a white guy from Canada, consider one more highly unlikely twist: he grew up affluent.

'Skinny white guy'

Throughout Nash's career, there have been many subtle and not-so-subtle remarks made about his skin colour. Sports talk show hosts and TV comedians have made the inevitable remarks about how amazing it is for a skinny white guy to be named the MVP in a league dominated by African-Americans. Even Nash himself hasn't shied away from it, often saying that he laughs whenever someone tells him that he is "pretty good for a white guy."

The media tends to use the same trope for Nash that it uses for other white athletes -- they have to work harder and play smarter in order to compete against more athletically gifted black athletes.

That conceit is insulting to the league's African-American players, implying they get by on natural skills rather than intelligence and determination. It also insults Nash's remarkable athletic ability. NBA analyst Bill Walton once noted during a telecast that Nash is the "least athletic point guard in the NBA." In fact, Nash has demonstrated amazing hand-eye co-ordination, agility and balance that allow him to make shots from nearly impossible angles. As a youngster, Nash was a talented soccer and hockey player and both his father and brother played professional soccer. To suggest that Nash is anything but a gifted athlete is absurd.

Wealthy disadvantage?

But you might say Nash's real disadvantage against his NBA peers wasn't his skin colour; it was his wealth. People rarely mention that Nash comes from an upper middle class background; his father, John, worked as a marketing manager at a financial institution and, as a teenager, Nash attended St. Michael's, a Victoria private school.

While Nash's family would hardly be considered among the truly wealthy, he certainly had a comfortable childhood -- something that cannot be said about most professional athletes, particularly in the NBA. Many African-Americans, deprived of traditional routes to success, focused on sports as one of the few avenues available to them. The ethos still exists today, much to the dismay of many in the African-American community, including NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who has often said that African-Americans should focus on scholastic rather than athletic achievement.

Hoop dreams are hardly unique to African-Americans and the NBA. In Canada, kids in rural areas dream of playing hockey as a way to escape small-town life; in Brazil, soccer can be a way to overcome the grinding poverty of favelas; and in the Dominican Republic, where batters have a reputation for being aggressive, baseball players tell each other that they "can't walk off the island" -- they have to hit their way off.

It takes an extraordinary amount of time and effort to make it as a professional athlete. For every player who makes a pro roster, there are literally thousands willing to take his place. To thrive in the world of pro sports, one needs to be supremely motivated, and for many athletes, a life of poverty fuels the fire in the belly that drives them to success.

Mystery magic

Yet Nash has been similarly successful without that desire to make a better life for his family. His fierce determination seems to come from an entirely different place. Of course, exactly what motivates him remains a mystery, even to his family. "How do you explain where drive comes from?" Nash's brother Martin told Sports Illustrated. "You can't."

One of the few people who can relate to Nash's inner drive is fellow NBA All-Star Pau Gasol. Like Nash, the Spanish-born Gasol grew up in an affluent family, and he seems to have a hard time describing what spurred him on to a career in the NBA. "I don't know," says the Memphis Grizzlies forward, who was in Vancouver recently to do some filming at EA Sports for their latest version of the NBA Live video game. "I never had to deal with anything drastic or dramatic in my environment. A lot of the guys in the league, they had to deal with a lot of stuff: death, jail, murders, poverty. In a way, that makes you tough and gives you that hunger. My motivation came from being ambitious and being a competitor. I always wanted to prove everybody wrong. I wanted to shut everybody up, prove to myself how good I am. Basketball was my passion. It's what makes me feel alive."

Gasol, like an athlete from any economic background, was able to succeed by focusing all his energy into his sport. For more affluent athletes, however, having that kind of tunnel vision can be more difficult because of the countless options they have in their lives. While poor athletes often see sports as their only path to success, the lives of more affluent athletes are filled with possibilities, which means that they might not be as willing to put up with the cut-throat world of sports. Why suffer through all that grief when there are so many other paths to success?

Privileged distraction

If anything, the opportunities that come with privilege could be a distraction that prevents athletes from making it to the Big Leagues. Gasol grew up in Barcelona, admiring Los Angeles Lakers star Magic Johnson. But Johnson's dazzling play didn't inspire Gasol to be an NBA player; it made him want to be a doctor, so he could work to help find a cure for HIV, which Johnson contracted in the early '90s.

Gasol, who grew up with parents in the medical profession, saw a career in medicine as a perfectly realistic goal, one that was far more reasonable than playing in the NBA. Unfortunately, for too many impoverished kids, the idea of becoming a research scientist seems about as likely as becoming the next Magic Johnson.

Of course, while Nash and Gasol should be commended for maintaining such focus in the face of the numerous opportunities on their horizon, it would be unfair to say that their privilege was a disadvantage. To say that poverty can drive people towards success could be used as an excuse to allow such conditions to exist.

Besides, such success can come at a high cost. The struggles that many athletes go through in their early lives can be harrowing and scarring. Consider the NBA's previous Great White Hope, Larry Bird. Bird grew up in rural Indiana with an alcoholic father and a mother who struggled to find enough money to clothe and feed her children. Things got so bad that Bird was often sent to live with his grandmother. One day, Bird's father called his mother and killed himself with a gun while she listened on the other end. Bird has often said that his poverty fuelled him to succeed in sports and continues to fuel him to this day. "The poorer person, the person who don't have much will spend more time playing sports to get rid of the energy he has," Bird told Esquire. "Why go home when you got nothing to go home to?"

For all the things that Nash has to be grateful for -- fame, success, money -- the thing he should be most thankful for is that his motivation, whatever it is, does not come from such a dark place.

Jon Azpiri is a freelance writer and the editor of Shared Vision.

Related stories in The Tyee: Jon Azpiri revealed the science of hockey pools, Charles Campbell argued sometimes sports isn't about politics, and Ian Gregson wrote about how runners with prosthetics may soon beat 'able bodied' sprinters. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: