You’ve heard of big 420 gatherings and Friday night cocktails. So what’s next — cocaine happy hour, the BC Heroin Store, meth raves and “tripping balls” at Playland?

Sounds like a hedonist’s utopia and a puritan’s hell. It may also be what comes to mind when you see the words “drug legalization.”

Take a moment to reconsider.

For several decades, “prohibition” has been North America’s prevailing drug policy approach. In this so-called “war on drugs,” law enforcement efforts are aimed at stopping the manufacturing and trading of illicit drugs. Or, to put it another way, the manufacturing and trading of dangerous substances that we currently leave in the hands of organized crime.

Over the past several decades, however, rates of drug use have continued to increase. Fentanyl hit the scene and a tragic overdose crisis has proliferated, claiming about 14,000 lives to date. There’s evidence of a concurrent methamphetamine crisis in Canada. Before that, crack cocaine use was epidemic in the U.S.

These outcomes are no coincidence. In fact, they’re a well-known phenomenon. The “iron law of prohibition” (a term coined by drug policy advocate Richard Cowan) maintains that as law enforcement efforts increase, so too does the potency of the drugs. Less bulky substances are easier to hide and transport. That’s what led to the preference for rum over beer and wine during alcohol prohibition, and the shift to crack from cocaine, and fentanyl from heroin. It’s an artificial demand for potency that’s created by the drug policy, not the people who use drugs.

The other unfortunate reality of restricting the supply of drugs is it becomes more attractive to sell them. The diminishing supply that results from enforcement measures and continued demand results in higher prices. Law enforcement efforts simply cannot overcome this economic reality.

Convincing you that prohibition isn’t working should be easy. What’s harder is to convince you that there is a viable alternative. After all, legalization can have downsides too.

Take alcohol. The brands are seemingly infinite, there are vendors on almost every block and the restaurant industry survives on its sales. Ads, celebrity endorsements and sports sponsorships provide a near constant barrage of messages suggesting that alcohol is life’s solution to our miseries and triumphs alike. This drug is virtually inescapable in our society.

Alcohol prohibition was a failure for the same reasons that prohibition of other drugs continues to fail. But this new corporate model for alcohol is also far from ideal. That’s because legalization is not a solution in and of itself.

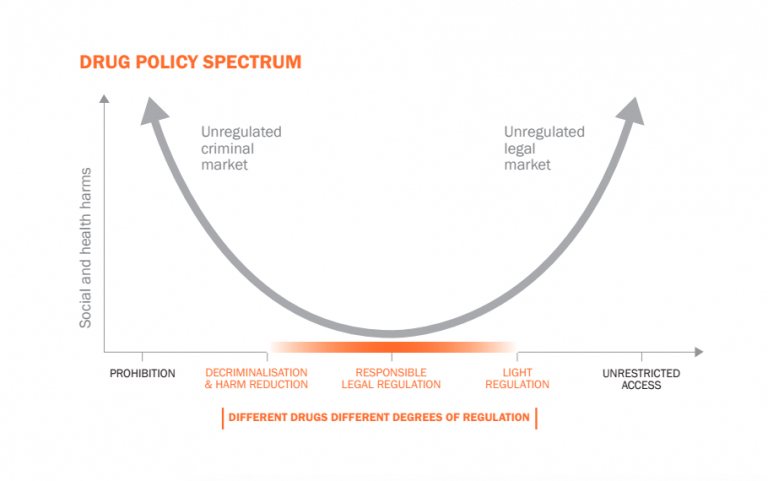

In public health, we use a U-shaped graph to explain drug-related harms. On one side there are immense societal harms from the prohibition of drugs. At the other extreme, unrestricted legalization can create just as many harms. The sweet spot is in the middle: legal, but with well-designed and strict regulation.

Responsible legalization includes essential policy strategies to keep consumers safe. It allows for evidence-based controls on the supply, quality, potency and labeling of drugs. While alcohol is only lightly regulated in terms of advertising and accessibility, when we take alcohol we know what we’re taking, we know how much we’re taking, and we can trust the labels that tell us that information. This lowers our chances of accidentally overdosing on the drug. It’s the same logic behind the cry for a “safe supply” of drugs to stop the ongoing overdose crisis.

I will not pretend that there is no logic at all behind prohibition. Though the average user was worse off during alcohol prohibition, with less advertising, lower availability, barriers to access and higher prices, overall alcohol consumption did decrease during that time. Prohibition makes intuitive sense. It just doesn’t hold up from economic or humanitarian perspectives because it results in far greater harm compared to any benefits.

Besides, we can capture those same benefits of prohibition (less advertising, lower availability, barriers to access and higher prices) under a well-designed legal approach. Under responsible legalization, we assume responsibility for the harms of the drugs rather than leaving them in the hands of those driven by profits — whether that is producers and dealers of illicit drugs or corporations selling legal ones like alcohol.

Effective legalization means combining evidence-based, drug-specific strategies with an education system grounded in harm reduction principles. One that doesn’t encourage drug use but isn’t childish enough to think teens can be scared out of experimentation. It means designing diversified approaches with regulatory controls that are catered to the unique qualities of each drug, approaches like the many that are already recommended by experts.

A new approach could take many forms:

- low-barrier prescription heroin or heroin buyers’ clubs for opioid-dependent individuals;

- an education-based process to become a licensed user of hallucinogens like magic mushrooms and LSD;

- a pharmacy model with education requirements and gatekeepers that ration access to cocaine to prevent compulsive use;

- energy drinks made of the relatively safe coca leaf plant;

- restricted-access venues that offer poppy tea or opium as a lower-risk alternative to heroin.

But amid an overdose crisis that has caused Canadian life expectancy to stagnate for the first time in over 40 years, there is an urgent need for access to safer legal opioids for those who need them. Initiatives have already begun to fill this need, from opioid vending machines to in-person safe supply programs. But under prohibition, they are limited to small pilot projects, barely making a dent in the overall death toll.

There is no shortage of expert guidance on the effective legalization of opioids and other drugs through a public health approach.

But alcohol is not the model we are striving for — let’s not limit our imagination to it. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: