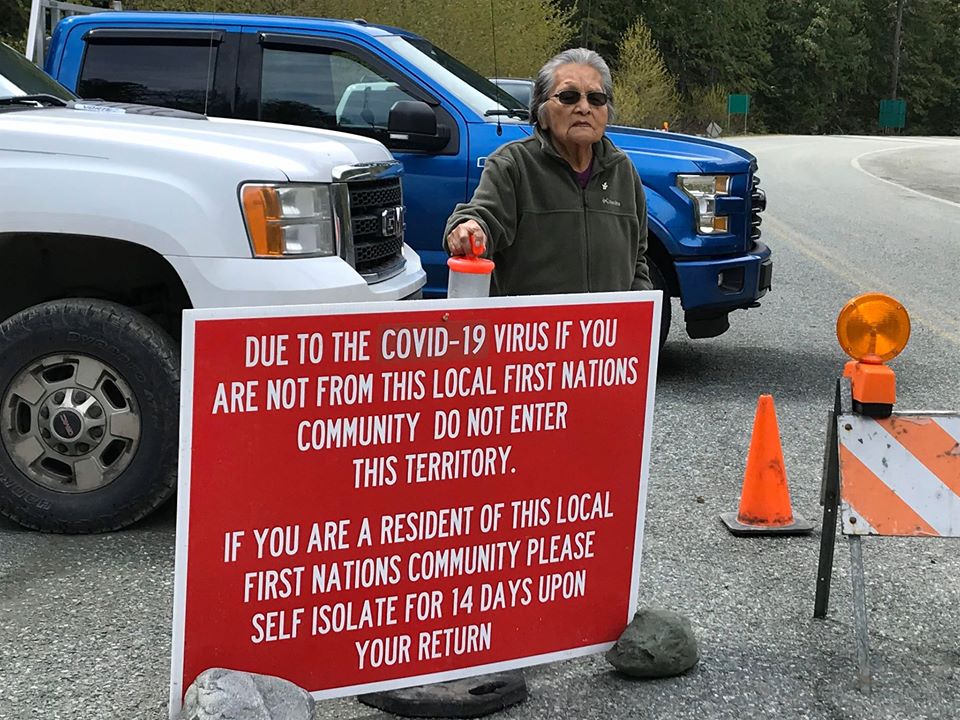

Two weeks after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the Tahltan Nation had formed an emergency management team. It asked community members to stay home, congregate only in small groups and maintain social distancing. Tahltan outside their territory in northwestern B.C. were asked to stay away, and barricades were built at community entry points.

The swift and sweeping actions paid off for the Tahltan and other First Nations, preventing a feared spread of the virus that could be disastrous for vulnerable communities.

But as the province holds in Phase 3 of its pandemic response and cases continue to rise, First Nations are again fearful of the risks.

The Nuu-chah-nulth people on Vancouver Island, after keeping the pandemic at bay for almost six months, have reported their first on-reserve case of COVID-19. Family members and close contacts of the individual are already in self-isolation.

Tribal Council president Judith Sayers said that once the province decided to enter its third phase of reopening, the spread into communities was inevitable.

She and other leaders are calling for health and safety supports that they say the province should have provided months ago.

Sayers said the government’s decision to move into a new phase of eased restrictions without consulting First Nations violated its commitment to accept the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“When we were in isolation, things were strange, but we felt in control,” said Sayers. But when the province moved into phase three, “we felt like we had lost control.”

“We had hoped with the B.C. UNDRIP implementation, we thought we would have the ability to consent to opening up the province. But there was no warning whatsoever.”

On Friday, B.C.’s First Nations Health Authority was reporting 74 on-reserve COVID-19 cases and 193 in total, representing about 0.14 per cent of status First Nations people in the province. While the cases are in line with provincial averages, they are about half what is being seen nationally.

But daily new infections have been on the rise, and Feddie Louie, director of the Tahltan’s Emergency Operations Centre, said that now is not the time for Indigenous communities to let down their guard.

“Our history tells us that pandemics tend to wipe us out. Spanish flu, smallpox, measles. All of those in our history have really devastated our population, so we are working really hard to ensure that our people are safe,” said Louie, who lives in Iskut, where social distancing, regular handwashing and wearing masks in public spaces are all enforced. Although residents still maintain smaller social bubbles, the lack of visitors has allowed some freedom within the remote community.

Chief Coun. Marilyn Slett of the Heiltsuk Tribal Council said that First Nations are at significant risk from COVID-19, with small, close-knit populations, high rates of inadequate and crowded housing, a large population of Elders and limited medical resources.

And she too said the provincial government has not done enough to help fight the spread.

“Heiltsuk, like other rural First Nation communities, have worked very hard keeping COVID out. We have issued lockdowns, foregone harvesting and trading opportunities, and refused entry to vacationers,” she says. “This has all been done at great economic and personal cost and largely without support and sometimes, in direct dispute with the B.C. government.”

Slett called on the province to release more geographically specific infection rates, so that remote communities would know about nearby cases.

“Knowing that a nearby community or community on our ferry route has a case is information we need to know in order to protect the members of our communities,” she said. “The Ministry of Health continues to refuse to share location information and has not justified the lack of transparency.”

Louie said that while Tahltan territory is normally overrun with hunters this time of year, she appreciates that most have respected the nation’s request to stay away. Land guardians and local residents have been patrolling the territory asking those who do come to leave, she said.

The province has confirmed that First Nations have the authority to restrict travel on their territory and that while hunting locally for food is an essential service, travelling to hunt is not. The Taku River Tlingit First Nation, north of Tahltan territory, also announced in August that hunting would be restricted to nation members and local residents.

Tahltan community members are asked to restrict comings and goings to essential travel only and those returning must self-isolate for 14 days.

“It only takes one person coming back to the community,” Louie said. “We are such a small community that we will have a huge spread before we even catch the infection.”

That has been the case in two recent outbreaks in First Nations communities, which have contributed to a rise in COVID-19 numbers in recent weeks.

Two weeks ago, the Nisga’a Lisims government announced there had been a COVID-19 exposure event at funeral services for respected Elder Joseph Gosnell. The infected person was from outside the community. Last week the nation announced three new cases within the Nass Valley. It did not identify which communities had been affected.

“It’s a difficult situation to navigate,” said Brandi Trudell-Davis, chief executive officer with the Nisga’a Valley Health Authority. “We want to ensure members are able to practise the culture while ensuring we follow strict policies. It’s a meshing of two worlds, each trying carefully to respect the other.”

Earlier this summer, the Haida Nation protested the reopening of fishing lodges that brought guests onto Haida Gwaii. On July 30, the province announced it was restricting non-essential travel to the archipelago, a move applauded by the nation.

The Haida Nation had a summer outbreak that began July 24, when the virus was introduced by a community member returning from a funeral off-island. On Aug. 28, the Haida Nation declared its outbreak over. In total, 26 people were infected.

Shannon McDonald, acting chief medical officer with the First Nations Health Authority, credits community members with swiftly self-isolating and preventing community spread. “When Haida Gwaii had their cluster, they worked really hard to maintain that bubble,” she said.

But Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council vice-president Mariah Charleson said safety depends on provincial government support, and that’s been inadequate.

In June, the Nuu-chah-nulth and other nations released a letter with four calls to action for the government, including helping the nations limit travel into their territories to residents, increasing testing, contact tracing and screening measures and better communication.

“These are the bare minimum for us,” said Sayers.

Charleson said the response has been inadequate and the government is missing a chance to demonstrate its commitment to the principles of UNDRIP.

“What an opportunity we have to work together in the real spirit of reconciliation,” she said. “It does bring worry to leadership, but we’re going to continue to push.”

Since the First Nations raised concerns in June, one rapid testing machine has been delivered in Tofino to serve the vast Nuu-chah-nulth territory across the northern part of what is known as Vancouver Island and some surrounding coastal islands.

In an emailed statement, the Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation said the province and health authorities continue to work with First Nations, including the Nuu-chah-nulth. “We know that for all of us our top priority is the safety of all community members, and in particular, Elders and knowledge-keepers,” wrote a spokesperson.

Sayers said remote communities also need greater access to medical and testing equipment.

And Sayers and Charleson also want more information on cases in the region, as many community members visit towns like Tofino and Ucluelet for their medical and grocery needs.

Sayers said while community vigilance and response from local leadership have been strong, only co-operation from the government can help them save lives.

“We need to be a part of whatever decisions are being made because it’s critical for our communities, and we’re being left out of those decisions,” she said.

The First Nations Health Authority’s McDonald said that while the initial COVID-19 response in Indigenous communities prevented its spread, pandemic fatigue may be contributing to recent clusters.

“Cultural ceremonies and funerals have been horrific for people. They’ve had a loved one who passed and, culturally, people gather in droves to come and support the family,” she says. “But when you get into those circumstances and people you love are in pain and there’s people you haven’t seen for a long time, the inclination is to hug, to take care of each other.”

Funerals have been hard, Charleson agrees, particularly with the passings of two Nuu-chah-nulth Elders in the last months.

But the recent passing of one of Charleson’s own relatives brought family and friends out to line the highway as family drove through, in a show of support for their loss.

“It provided closure of some sort, even though it’s so different from the way we would typically gather,” said Charleson. “In our culture, we like to celebrate and get together.”

McDonald adds that as days get colder and nights longer, particularly in the north, socializing will become more challenging and maintaining small, secure bubbles will become especially important.

“We’re in this for the long haul. People keep saying, ‘When’s it going to end?’ We don’t know the answer to that. And it may never be the same as it was before this,” she says. “We’re looking forward to an effective, safe vaccine, but that’s going to take a while. So, we just have to get used to how we work in a safe way and how we have relationships through all of that.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Health, Coronavirus

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: