[Editor's note: On Monday, a contingent of federal Conservative cabinet members will meet with First Nations leaders in British Columbia to promote the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline. The push comes following a special report to Prime Minister Stephen Harper indicating that negotiations between Enbridge -- the pipeline's proponent -- and B.C. First Nations are a mess. It also comes just ahead of the final ruling from the National Energy Board (NEB) that will either approve or reject the pipeline; a decision that is expected to come by the end of this year.

At the request of NEB regulators, Enbridge hired consultants to forecast and map exactly where bitumen would go if spilled from any rupture along the pipeline route, and how much of it might be expected to enter the environment before a leak was isolated. Journalist Chris Wood, in collaboration with Alternatives Journal, unearthed the consultants' graphic evidence.]

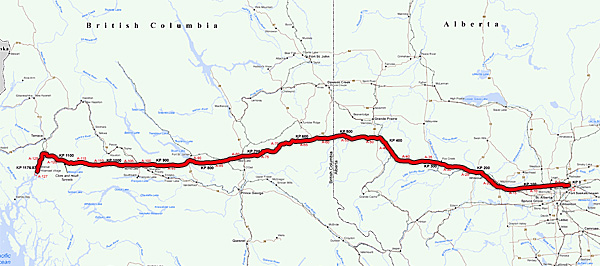

The proposed pipeline will, in fact, be two pipelines. One of them, 36 inches in diameter, will push tar sands bitumen diluted with solvent from Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta, to Kitimat, B.C. -- delivering more than half a million barrels of petroleum slurry a day to the West Coast port. A second pipe, 20 inches across, will pump 193,000 barrels a day of solvents, separated from the bitumen in Kitimat, back to Alberta for reuse.

The twin pipelines' 1,177-kilometre route will cross 669 fish-bearing streams, scores of wetlands, the headwaters of the two most important western Canadian rivers -- the Peace-Athabasca and the Fraser -- and two mountain ranges. Much of the route is remote from access roads.

In January 2011, the NEB asked the pipeline company to say more about how it would reduce the "potential for far-reaching environmental and human consequences in the event of a hydrocarbon release."

In its reply, the company said that its design decisions, will "contribute to minimizing" the risk from a spill. It illustrated the importance of route selection with maps (prepared by B.C.-based consultants AMEC Earth and Environmental Inc.) superimposed on aerial photographs to show where several lengths of proposed pipeline had been rerouted to reduce risk.

As well, the company submitted, "Northern Gateway's entire pipeline and terminal operations will be constantly monitored, including pipeline operating pressure, pipeline flows, pumps and pump station operation and leak detection. Should operating abnormalities or a pipeline leak occur, alarms will notify qualified operators and the pipeline system will be shut down."

In other statements, the company has further promised to pre-position equipment, including booms and oil-skimmers, at various locations along the route, and says it will develop detailed spill containment and clean-up plans based on "existing protocols" used on its other pipelines, "augmented by project-specific emergency response plans."

Nonetheless, the pipeline company hired Australian engineering company WorleyParsons Inc. to calculate what would happen at each kilometre of the proposed route if, despite its precautions, one of its twin pipelines did in fact rupture.

The task required examining landscapes such as foothills, plateaus and mountains, considering the inclination of the pipelines at the point of spills, and the location of emergency shutoff valves. In late 2012, WorleyParsons reported its findings in sets of images and graphic data.

Using that information, we've identified particularly vulnerable areas -- and exactly how much they would be exposed to should a spill occur.

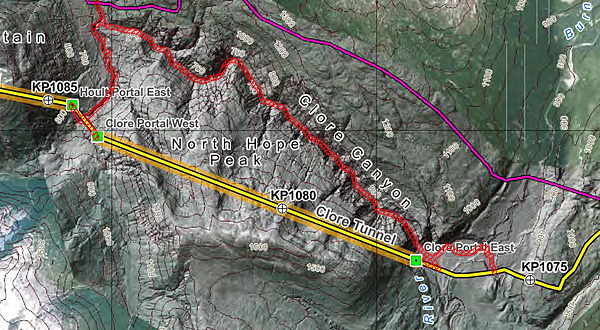

Remote mountain tunnels

The proposed pipelines cross the southern tip of B.C.'s Burnie-Shea Provincial Park and Protected Area 101 km east of Kitimat. The only access to this nearly 35,000-hectare backcountry is by helicopter, float plane or foot. There, the pipelines enter the first of two tunnels that will carry them under the Coast Mountain range. Emergency crews trying to clean up a rupture at the "Clore Tunnel East Portal" would have to travel seasonal forest service roads across more than 60 km -- as the crow flies, so further and less directly on the ground -- of Canada's most vertical terrain, indicated here (as in the original WorleyParsons documents) by dense elevation contours. Spilled oil or solvent would flow down the Clore River toward the Skeena.

The two tunnels are among changes proposed in the pipeline's route, replacing a long oxbow (purple in consultant AMEC Earth and Environmental's illustration) through a remote mountain canyon plagued with rockslides and avalanches. In the company's estimation, the tunnels will reduce the anticipated spill risk -- a factor of a spill's likelihood of occurring, and its potential consequences. Whereas the previous route would have incurred the most extreme spill risk factor of 25, AMEC evaluated the tunnel plan as posing a minimal rating of one. Enbridge also plans to install check-valves where the pipelines enter or emerge from their tunnels.

Even so, according to this graph, ruptures at or between the two tunnel portals -- where the pipelines are briefly exposed between the Clore and Hoult tunnels, would still release nearly 6,000 barrels of bitumen. That's more than the total amount that another company, ExxonMobil, acknowledged was leaked after a March 2013 pipeline breach in Arkansas sent crude running like a river down a suburban street.

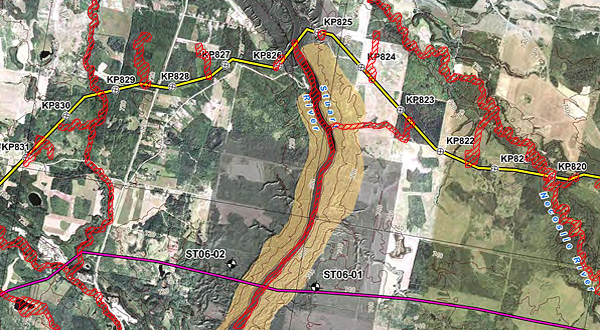

Crossing a salmon highway

Just south of Fort St. James, B.C., the pipelines would cross the Stuart River. The Stuart is a vital travel corridor for chinook and sockeye salmon. As many as a million fish travel past the pipelines' planned crossing point to spawn further upstream every year. According to BC Parks, the river is also a critical habitat for endangered white sturgeon. Elk, moose, bears, swans and eagles also use it as a travel corridor. WorleyParson's map shows how oil or solvents leaking from the two pipelines at any point for kilometres on either side of the crossing would flow down smaller tributaries to reach the Stuart River.

Here, too, the company realigned its proposed route, taking the pipeline across the Stuart River further north than originally planned to avoid "very extensive deep-seated slides... on east and west approaches."

The unstable terrain would have raised the likelihood of a pipeline rupture to the highest possible rating of five. Multiplied by the equally extreme potential consequences of a spill in such a critical environment, the original course was assessed as posing the maximum risk level on the 25-point scale. The company ranks the risk of the realigned route, plus other measures including a tunneled "crossing" of the Stuart itself, at a minimal one to two points.

Notwithstanding the reduced risk assessment, the associated spill volume graph predicts that a failure at any point in the first few kilometres west of the Stuart River would release some 30,000 barrels (1.26 million U.S. gallons) of bitumen.

That estimate foresees a larger spill than the worst disaster in Enbridge Inc.'s history to date, which saw a million gallons of diluted bitumen flow into Michigan's Kalamazoo River in 2010. A subsequent U.S. investigation blamed the company's "culture of deviance" from safety norms for its slow response to the leak; operators had repeatedly dismissed automated warnings that the pipeline was losing pressure. Clean up has so far cost more than $1 billion.

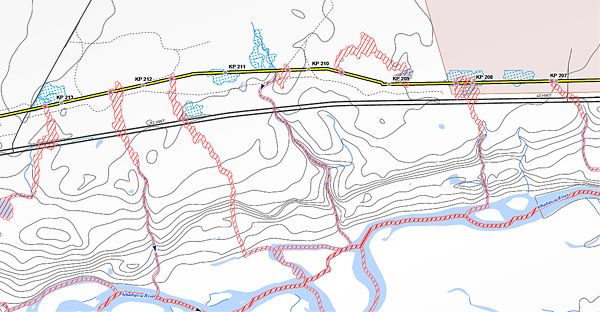

Exposed Athabasca wetlands

Enbridge proposes to build a head-end collection point and terminal for its pipelines at Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta, near the North Saskatchewan River. That river flows eventually into Lake Winnipeg. The pipelines' route west would leave the Saskatchewan basin and spend the next 500 km crossing the headwaters of the Athabasca, which later joins the Peace and Slave rivers to contribute its flow to the Mackenzie and the Arctic Ocean.

The Athabasca's headwaters already receive effluent from pulp and paper mills, but until now have been relatively free of the hydrocarbons entering it downstream from tar sands extraction operations.

The pipelines' planned route hugs the Athabasca River particularly closely around the town of Whitecourt, Alberta. The associated spill volume graph for this portion of the route indicates that bitumen or solvent from any rupture would impact high-value, hard-to-clean riparian wetlands. Those ruptures could release 15,000 barrels of bitumen before being controlled -- about three times the amount that leaked from ExxonMobil's Pegasus line earlier in 2013. ![]()

Read more: Federal Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: