[Editor’s note: The population of aboriginal people in Canada is growing fast, and is on average 13 years younger than the rest of Canadians. Yet both on and off reserve, aboriginal students remain significantly outpaced by their non-aboriginal peers in both high school graduation and post-secondary participation rates. The best people to recognize how to reverse these trends are aboriginal people themselves. In "Call of the Spirit," a Tyee Solutions Society series that kicks off today, reporter Katie Hyslop profiles six aboriginal post-secondary graduates about their experiences, asking them, "How would you change post-secondary education to make it a more welcoming and viable option for aboriginal people?" Up first: Shawn A-in-chut Atleo, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations. Look for more in coming days.]

Like most youth fresh out of high school today, Shawn A-in-chut Atleo didn't have a plan or even much care about his post-secondary education when he attended Trinity Western University in the late 1980s. The current national chief of the Assembly of First Nations did not major in political science, First Nations studies, or even education. He excelled in soccer.

"I was really good in soccer, got great marks," Atleo told The Tyee Solutions Society with a smile, at our Vancouver office for an interview this past May.

Accepted into Simon Fraser University, University of British Columbia (UBC), and the private Christian Trinity Western University (TWU), Atleo chose TWU because it was far away from mom and dad. Just 17 years old, he was ready to get out from underneath the watchful eye of his parents, both educators and academics in their own right. Two years later, Atleo was married to his high school sweetheart and left school to focus on starting his family and career. After a failed attempt at running a café, he eventually joined the staff of a family addictions treatment centre on Meares Island, near Tofino.

A 26th generation hawilth, or "hereditary chief," Atleo says it wasn't until he formally began his involvement in band affairs in 1999 that he finally realized his true calling was something he had been involved in all along: politics.

"When you are born First Nations within the last number of generations, you're born into politics because it swirls around your life everyday," he said, his expression now turned serious.

"And if you care, as I do and so many of our people do, you want to do something about it."

'I struggled in school': Atleo

As a second-term leader of Canada's largest First Nations organization, Atleo has memorized his biography from doing interviews just like this. But although he has the speech down pat, his smiles, gestures and small laughs reveal the happiness and pride his family and nation give him.

When he was growing up, Atleo's family split their time between the reserve village of Ahousaht, located just north of Tofino on the west coast of Vancouver Island, and the city of Vancouver, on Coast Salish territory. His father, Richard Atleo, moved the family back and forth between Vancouver and Ahousaht in the 1960s and '70s so he could work on his bachelor's and master's degrees at UBC. Both of Atleo's parents would go on to earn PhDs at UBC later in life -- his father's in education and his mother's in philosophy. Atleo senior was the first aboriginal person to receive a PhD from the university.

Atleo junior was in elementary school the first time he moved with his family to Vancouver, living initially on the Musqueam territory now known as the UBC endowment lands. Later they lived in East Vancouver where he attended Tyee Elementary, which he fondly referred to as being "pretty hardcore" when he attended in the 1970s. His schooling had started in Ahousaht, however, and right away he didn't like it.

"I moved over 20 times (during childhood), and my first principal and my first teacher was my dad. The substitute teacher was my mom. So I was in school during the day (with them), and then I saw the principal and my teachers at dinner every night," Atleo, now 46, recalled.

"There were aspects of school that I enjoyed growing up, but like a lot of First Nations young people, I struggled in school and it was a big struggle."

Despite hindering his enjoyment of school, his parents would prove to be his biggest academic role models. His father, the eldest of 17 brothers and sisters, spent 12 years in residential school before pursuing university. Atleo's paternal grandmother also encouraged her children and grandchildren to pursue education, telling them "We've been fighting all our lives. We should no longer fight our fights with our fists. We should fight our fight with education."

But the legacy of residential school experiences that went back generations -- students stripped of their languages, cultures and childhoods, only later to often be forced to send their children away to the same fate -- hung heavily over Atleo's reserve. As a child, Atleo remembers witnessing his community suffering from widespread alcoholism, unemployment, abuse and a grim future.

"It was the best of family, culture and place, in our territories off the west coast of the island," he said, "and then it was also some of the most traumatic, difficult, violent and dysfunctional (times). And that's a statement of reality in many First Nation communities and upbringings."

The transformative years

Atleo was seated as a hawilth in 1999, after his father gave up the position, and was given the name "A-in-chut", which means, "Everyone depends on you." One of his first acts as a hawilth -- the Ahousaht nation have three hawilth sitting at all times -- was forging a protocol that linked the hereditary chiefs with the elected chief and council introduced under the federal government's Indian Act.

Unlike the elected chief, the hereditary chiefship is passed down by blood, and Canadian law does not recognize its leadership. It is not uncommon to find both kinds of leadership in First Nation communities in B.C.

By the time Atleo took on his hereditary duties, he had long abandoned his dreams of soccer playing stardom but had worked his way up to become the executive director of the Meares Island addictions treatment centre. Once just an observer of the trauma inflicted on his people by colonial oppression, Atleo was now wrestling with the repercussions first hand through his addicted clients.

Long interested in going back to school, Atleo's work experience allowed him in 2001 to enrol without a bachelor's degree in the online master's program in adult learning and global change offered by the University of Technology Sydney in Australia. The program was part of an international partnership between the University of Technology, the University of British Columbia, Linköping University in Sweden, and the University of the Western Cape in South Africa.

"I was able to do my learning and stay situated (on Meares Island) at the same time," he said.

"I found it really a transformative two years for me. I had no idea how the Canucks were doing in the league, no idea what was happening in the outside world whatsoever -- completely focused on learning and my work and spending time with my family, my wife and two kids."

He graduated in 2003, the same year he began serving the first of his two terms as British Columbia's regional chief in the AFN. He held that role until 2009 when he ran for national chief. He won, becoming at age 42 the youngest chief since 37-year-old George Erasmus was elected in 1985, and the first chief from B.C. in 33 years. For a small community eight nautical miles north of Tofino, Atleo's election was a huge event.

Lewis Maquinna George, another Ahousaht hawilth, says Atleo's win cemented his stature as a community role model in Ahousaht. "It's a real blessing for us to have somebody like that," George told The Tyee Solutions Society from his home in Tofino. "One, it's a role model for the children of our tribe -- not only our tribe, all of the Nuu-chah-nulth people -- to say that if you're wanting to do something... the sky's the limit."

"A few years ago in our 14 (Nuu-chah-nulth) tribes here," he said, "there was no doctors, there was no lawyers, there was no dentists, all of these things that seemed to have been out of our grasp. And now we are telling the kids, 'No, if you're wanting to be a doctor, it's there for you.' So it's being a role model not only for Ahousaht but for the rest of the tribes, it's phenomenal."

Indeed, the successes of not only A-in-chut Atleo, but of his whole family starting with his parents, have reverberated across the Nuu-chah-nulth nations.

"In his family, the administrator for the school in Ahousaht, she went to get her master's degree and she runs our entire education program in Ahousaht," said George. "And then another member of his family went to UBC to become a lawyer."

"In other families we've had people go in to get their teaching degrees: we have a school up there in Ahousaht that goes from K-12 and there's a few of our own teachers that have gone out to get their teaching degrees. So it does make a difference when you have role models out there to look at."

Education candidate

Atleo's credentials, along with his focus on the importance of learning earned him the label of "education candidate" during the 2009 AFN national chief elections. It's a label he regards as imposed by mainstream politics, but one that still fits him.

"My interest for sure has to do with learning, more broadly, and education is one aspect of learning," he said. But not the only one, he added. First Nations "ways of knowing in the world," he said, are much different from western methods.

"First Nations are about supporting and holding the notion that many different ways of viewing the world, a diversity of ideas, can be equally respected, equally held in mutual recognition, at least, of one another," Atleo explained. "So it's a very different way of viewing the world, and it is about learning."

Intentionally or not, education has become a big theme in First Nations politics in Canada since Atleo was elected chief in 2009 -- for good reason.

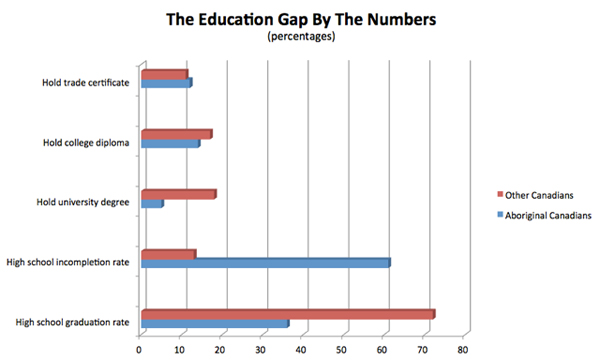

The aboriginal population in Canada is booming and overwhelmingly young. In 2006 the median aboriginal age was 27, compared to 40 for the rest of the country. Nearly half of aboriginal Canadians -- 47.8 per cent -- are 24 and under: the age group most likely to attend school and post-secondary.

Yet annual funding growth for First Nations education through on-reserve schools or the federal Post-Secondary Student Support Program (PSSSP) aimed at students pursuing advanced education, has been capped since 1996 at two per cent a year -- barely keeping up with inflation, and only about half the growth rate among school-age aboriginals.

In addition to the need to raise Inuit, Metis and First Nations high school graduation rates that are far lower than the Canadian average, those groups' participation in post-secondary education also needs to increase.

In pure economic terms, post-secondary graduates earn more: workers with trades or a college certificate earned $7,200 more than a high school graduate, while university degrees bring in an average annual income $23,000 higher than a high school graduate's.

'Blow up every department of philosophy'

But time is running out, Atleo said, and Canada needs to invest in indigenous youth now in order to avoid "losing" another aboriginal generation.

"We just simply can't afford that: not in human potential terms, not in relationship terms," he said. "The economics also offer an important imperative for the future of the country, for us to invest in indigenous young people and to do it now. We cannot waste any time moving on with this."

The first step, he said, will be big structural changes to post-secondary education, like putting more aboriginal people in positions of power at post-secondary institutions -- Atleo is the first chancellor of Vancouver Island University, appointed in 2008 -- as well as making aboriginal history and culture part of mandatory curriculum, particularly in faculties like law and philosophy.

"John Ralston Saul, one of the leading thinkers and authors in this country said, 'If we wanted to change the reality of First Nations in this country, we should' -- and these are his words -- 'blow up every department of philosophy in every major institution in this country,' " said Atleo.

Canadian institutions, he added, need "indigenous ways of knowing" to be introduced and supported in a structural manner in the schools of philosophy. "What [Saul] said is the big missing conversation is between First Nations and the immigrant population of this country, and I support that kind of a sentiment, (as well as) ensuring that our people not only have access to other forms of post-secondary learning, but other forms of post-K-12 learning and skills training."

Atleo is pushing leaders of the post-secondary institutions he meets to make these changes. He cites VIU's choice of an aboriginal chancellor and UBC's First Nations House of Learning as examples of success.

VIU President Ralph Nilson says it was Atleo's pushing for aboriginal representation at the school that inspired him to recommend the then-provincial chief for the job.

"He asked me some very important questions in terms of the role of First Nations and aboriginal people in governance at the University," Nilson recalled.

"So the challenge for Shawn was that I came back to him, probably within half a year from that conversation, and said, 'Well here's an opportunity for you. What do you think? Are you going to step up to the plate?' "

Not only has Atleo stepped up to the plate, Nilson says he believes the experience has made it easier for the national chief to speak to other university administrators about increasing aboriginal presence.

More educated women

But change isn't happening fast enough for Atleo, and he isn't impressed with the federal government's record of improvements. The past two years have been tense for relations between First Nations and government, particularly regarding education.

In 2011 the AFN and the federal government launched the Canada-First Nation Joint Action Plan, promising steps to improve the lives of First Nations people on and off reserves in areas including housing, effective governance, self-sufficiency and education.

But two years later, First Nations have grown restless waiting for change. Out of that restlessness a grassroots protest movement, Idle No More, was born. High-profile marches, hunger strikes and road blockades started spreading across the country in November 2012, leading to a controversial meeting in January between Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Atleo, along with several other chiefs. The opportunity to quell the anger and spark change, however, failed to do either.

A draft federal Aboriginal Education Act the government hopes to introduce in 2014 has been widely panned by First Nations groups for being written without their input.

CBC reported on Friday, June 21, that a follow-up meeting between Atleo and the prime minister finally took place in Ottawa the day before. Although they discussed several issues, including treaties, and recent federal legislation concerning safe water and property rights for First Nations women and children on reserves, there was no indication that progress on education reform took place.

Going their own way

Some First Nations are academically thriving in spite of the stalled status quo. A Mi'kmaq community in Nova Scotia has achieved an almost 90 per cent high school graduation rate. But that isn't the norm, and Atleo isn't content to sit and wait for government to fix their problems.

"We're reaching out to Canadians more mainstream. We're reaching out to the philanthropic community," he told The Tyee Solutions Society. "The international NGO community groups that build schools and deploy clean drinking water to schools in Africa and South America are now turning their attention to Canada," he said, adding UNICEF, Habitat for Humanity and Amnesty International to the list of groups working with First Nations in Canada.

"(Here is) a question that we should ask not only each other but Canadians more broadly: are we okay with waiting for some future leader to come along and decide that things are going to be different? Or is Canada going to be gripped by this and say that we share in this responsibility?"

His drive seems to be working. VIU President Nilson says that since Atleo became national chief in 2009, aboriginal education has become one of the top three items post-secondary lobbyists like the Association of Universities and Colleges Canada and the Association of Community Colleges of Canada raise with the federal government.

"That was not as clearly articulated prior to Shawn's leadership. That to me is a clear demonstration of the kind of impact that he's had by the time that's he's spent with universities, with colleges, to help them to understand the importance of education in bringing equity, equality and respect within the country," said Nilson.

Atleo says he isn't giving up on government to make changes for aboriginal people, because that means giving up on Canadians. Instead he says it's time for all sides to accept their share of responsibility for the current state of aboriginal communities and start trying to make it better for the current and future generations.

"I'll continue to reach out to Canadians more broadly, to philanthropic, non-profit organizations, student unions, colleges, secondary schools, post-secondary institutions, and we'll bring the story right to the United Nations, the Organization of American States, and we'll make sure that everyone who we can share this with knows," he said.

"Perhaps governments will find it in their hearts and minds to make the kind of policy shifts that are needed desperately right now. I will continue to hold out hope that that's possible."

Until that day comes, Atleo won't stop educating Canadians on aboriginal people's right to learn. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: