Last month British Columbians learned the public-private partnership to finance and build the Port Mann Bridge had fallen through. The provincial government now intends to go it alone, spending $3.1 billion to erect a new 10-lane bridge and widen the road on either end. The government is betting it eventually will recoup the costs by charging tolls starting at $3 per trip and likely to rise.

When the news broke, most of the debate was about whether the deal had been mismanaged. But a team of sustainable community design experts at the University of British Columbia got out their calculators and pursued a different question. They started with the assumption that public money isn't unlimited. They wondered how many citizens would get a real benefit from the finished bridge. And they folded in a goal that B.C. Premier Gordon Campbell espouses: reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

What other transportation infrastructure, they asked, could we instead have for $3.1 billion?

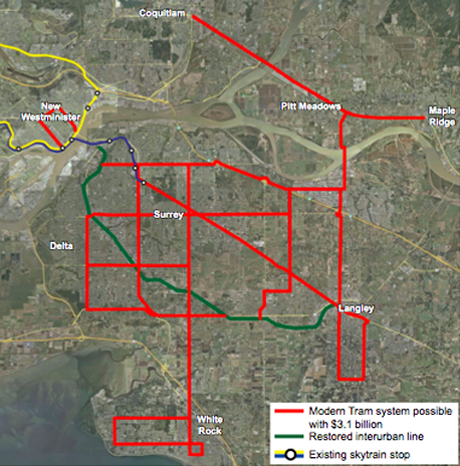

By the time Prof. Patrick Condon and researcher Kari Dow at the UBC Design Centre for Sustainability finished punching in the numbers and mapped their results, they produced a startling alternative vision. For the same money, concluded the team, the government could finance a 200-kilometre light rail network that would place a modern, European-style tram within a 10-minute walk for 80 per cent of all residents in Surrey, White Rock, Langley and the Scott Road district of Delta, while providing a rail connection from Surrey to the new Evergreen line and connecting Pitt Meadows and Maple Ridge into the regional rail system.

Big savings on greenhouse emissions

"We were not trying to show a detailed system plan, we just were trying to demonstrate that it seems to be a very lot of money for one bridge when compared to an alternative way of spending the same amount," said Dow.

If half of the roughly 40 million annual trips anticipated for the new bridge were shifted to such a tram system, it would amount to a reduction of the roughly 10,000 metric tons of GHG per year, a reduction equivalent to taking more than 21,000 cars off Lower Mainland roads completely. This amount does not include the likely far greater reductions of car use throughout the south of Fraser region that would result from the light rail network, said Dow.

Compared to the 200 km grid of light rail, the Port Mann Bridge, including approach spans, is a mere 2,093 metres long, though the entire project actually extends 37 km and includes widening Highway 1, adding two lanes each way on the east side of the bridge and an extra lane in both directions on the west side.

Dow and Condon factored in the cost of tearing down the original Port Mann Bridge and erecting a brand new one, as current plans dictate. They based their comparative figures on proven costs per kilometre for building a type of high-speed light rail tram widely used in places like Alicante, Spain; Budapest, Hungary; and Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Changing the commute culture

They point out that while building a bigger Port Mann Bridge reinforced commuting patterns in the region, building a robust light rail network likely would change how development occurs in the region, eventually shortening commutes as businesses elect to locate at various new public transit nodes.

"The Port Mann project is propelled forward by assumptions that are 20 years out of date. Commuting patterns are changing rapidly. The commute from Surrey to downtown Vancouver is relatively rare and getting even rarer each day. Jobs continue to move closer to housing all across the eastern part of the metropolis. What is needed is a system that gets us out of the car and serves our emerging complete communities, not guts them," said Condon.

Original vision changed

The Port Mann bridge deal started with a privately financed plan to twin the existing span to allow traffic to move faster through what's become a commuting choke point. The plan changed, and became more expensive, when the government announced it had decided, with its private partners, to tear down the old bridge and build a much bigger new one. Then on Feb. 26, the project's main private partner, Australian infrastructure firm Macquarie Group, dropped out as its stock price plummeted and credit tightened amidst the global financial downturn.

"We have determined that a traditionally financed arrangement is the better way to proceed at the current time," Falcon said when the deal fell through. "With P3s, every deal has got to stand on its own merits. If we can't make a deal that makes sense for us and for taxpayers, we don't do it."

The province will hire two of the remaining partners -- Peter Kiewit Sons Co. and Flatiron Constructors Canada -- to design and build the bridge at a previously agreed cost of $2.46 billion. Those private contractors will be obligated to absorb any cost overruns. The rest of the $3.1 billion price tag is for financing and maintenance costs.

Billions earmarked for mega-projects

The B.C. government is intending to build a number of other large transportation infrastructure projects, including a $1 billion Perimeter Road truck freeway between Deltaport and Highway 1, the $1.4 billion Evergreen Line extending SkyTrain to Coquitlam, and a $2.8 billion, 15 km SkyTrain spur along Broadway in Vancouver out to the UBC campus.

The expenditures are so huge, notes Condon, that "whatever the merits or demerits of the Port Mann proposal, we feel that the taxpayer only has so much in their pockets and these expenditures are gigantic. A real comparison between reasonable alternatives would enhance our ability to choose wisely. How we deploy the available billions on transportation infrastructure over the next 10 to 15 years will determine how sustainable this region will or won't be 100 years from now. We simply have to get it right."

When the UBC SkyTrain line was announced last spring, Condon and Dow produced a study showing that the same money could build a 175 km lattice of light rail lines restoring Vancouver's former trolley system and extending into bordering locales.

Related Tyee stories:

- A Prius for Every Student

That's what you could do at UBC, for the price of its new Skytrain line. - 2010 Games Traffic Plan a Permanent Roadmap?

Officials hope citizens will embrace public transit beefed up for Olympics. - No Fares! (series)

Time for a free ride on public transit.

Read more: Transportation, Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: