Vancouver's top drug policy official and B.C. public health physicians believe addicts might be treated by giving them psychedelic drugs, and they hope the city will lead in exploring the controversial approach.

Powerful hallucinogens such as ayahuasca and peyote could offer addicts and other sick people "profound benefits," Donald MacPherson, Drug Policy Co-ordinator for the city of Vancouver, told The Tyee.

MacPherson is co-author of a report published by the city in November that puts ayahuasca and peyote in the category of "benefit," based on their traditional use by indigenous cultures and on documented studies by researchers.

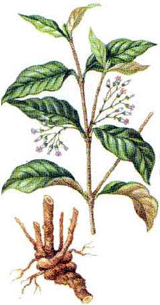

Ayahuasca, an Amazonian, vine-based tea brew, is cited as "non-addictive" and as a "powerful therapeutic tool" used for centuries in Peruvian and Brazilian ceremonial settings. Peyote, the report notes, is "legally administered as a ritualistic sacrament by the members of the Native American Church as an antidote to alcoholism."

The report, titled Preventing Harm from Psychoactive Substance Use, recommends that the city forge ties across all levels of health care and communities and facilitate "exploration, study and application of traditional medicines and rituals and of evidence-based alternative approaches towards the prevention, healing and recovery from problematic substance use."

"Our report is certainly pushing the envelope, but these drugs could have profound therapeutic and spiritual benefits," MacPherson told The Tyee. "We think that demonizing these psychedelic drugs is totally bizarre, and their benefits should be explored."

The Vancouver city report followed a report published by The Health Officers Council of B.C. which recommends that restrictions be loosened on the use of psychedelics as therapeutics in controlled medical settings.

Return to Hollywood Hospital?

If Vancouver's officialdom were to follow such recommendations, it wouldn't be the first time the city found itself at the centre of a worldwide interest in the potential healing properties of hallucinogens.

In the late 1950s, New Westminster-based Hollywood Hospital was a leader in therapeutic psychedelics, almost a decade before Timothy Leary encouraged the masses to "turn on, tune in and drop out" on acid. Founded by eccentric American entrepreneur Al Hubbard, Hollywood Hospital catered to a mixed clientele of American celebrities and Canadian politicians given LSD to treat alcoholism, drug addiction and psychological burn-out. For almost a decade after LSD was criminalized in North America in the late 1960s, Hollywood Hospital served up therapeutic LSD before the provincial government pulled funding in 1975 and the hospital closed.

Pharmaceutical drugs soon became the government-sponsored substances of choice. But a number of academics refused to give up the fight for therapeutic psychedelics and today, LSD, MDMA ("ecstasy") psilocybin ("magic mushrooms") and ibogaine are being used to treat everything from cancer pain to addictions to anxiety disorders at prestigious universities and private research centres.

Ibogaine in Vancouver

In Vancouver, Prince of Pot Marc Emery opened up a therapy centre to treat dozens of downtown eastside drug addicts with ibogaine in 2003 before he ran out of funds. Now a group called The Iboga Therapy House has re-started the program and is looking for Health Canada funding.

Meantime, ayahuasca, another psychedelic plant brew said to treat addiction, can be purchased at The Urban Shaman on Hastings Street, and a Vancouver group called Traditional Amazonian Medicines Society (TAMS) organizes trips to Peru for locals looking to sample ayahuasca in the remote jungles with an Amazonian healer.

Unlike LSD and ecstasy, ibogaine and ayahuasca aren't criminalized in Canada, though they are in the States, so Vancouver is in a unique position to host start-up therapy programs.

Vancouver Drug Policy Co-ordinator MacPherson has no illusions that three levels of government will quickly and easily heed the calls to embrace the therapeutic potential of some hallucinogens. He told The Tyee that numerous clinical trials need to be carried out by researchers before the pros and cons can be weighed out and that will necessitate provincial and Health Canada approval and funding.

"Given the political climate around the NAOMI [heroin addiction treatment with heroin] trials, we're on rear-guard action in terms of gains we've already made, and don't want to jeopardize that work," said MacPherson.

"But I think you'll see more interest in therapeutic psychedelics in the coming year," MacPherson said, adding that "these types of programs are usually pushed by academics. The Ministry and groups like the Coastal Health Authority aren't research labs. They'll say, 'Show me the evidence that these drugs work' and the problem is that while there's a lot of anecdotal evidence, there's not much recent peer-reviewed research around psychedelics because of a completely wrong-headed approach to addiction and of course, the war on drugs."

BC health officers: loosen laws

Opponents of using therapeutic psychedelics are difficult to find among medical researchers. While there are a number of published medical papers around recreational users who took street ecstasy (which is often adulterated with other drugs or toxic chemicals), even toxicology experts are hesitant about writing off many of these drugs.

One Canadian Medical Association Journal paper written by University of Toronto professor Harold Kalant in 2001 discussed the varied potentially fatal risks of taking street ecstasy but he added that there was "no evidence" that taking the drug would lead to addiction and even said that the drug "may be of potential value as an aid in psychotherapy" though "similar claims were made earlier for MDA, LSD and other hallucinogens but...no lasting benefit was found in a 10-year follow-up study of patients treated with LSD" and "no comparable study has been conducted on patients treated with MDMA."

Kalant adds that a primary issue in doing clinical studies might be "difficulty obtaining the drug since its change in legal status."

The Health Officers Council of B.C. gives the nod to medical uses for a broadened range of psychedelic drugs in their report "A Public Health Approach to Drug Control in Canada" released last October.

The report lays down strategies for approving and regulating various criminalized psychedelic drugs for use in clinical settings. It points out that "drugs such as LSD and MDMA which have been shown to have potential psychotherapeutic benefits when used in controlled therapeutic environments, could be used with registered and trained psychiatrists and psychologists."

The report concludes, "there is a growing consensus in Canada that there should be an exploration of other drug control mechanisms, with possible adoption of strict regulatory approaches to what are currently illegal drugs."

The group calls for "a new balance point in the drug control policy spectrum, occupying the middle ground" that minimizes "the multi-faceted negative effects of harmful substance use, while also minimizing the harms caused by drug laws themselves."

'So much potential'

Advocates realize that research groups interested in pursuing psychedelic treatment programs, particularly the criminalized substances, could have trouble convincing Health Canada to get on-side with endorsement and funding. "But, there's so much potential with these substances that as a society we're missing the boat by not incorporating them into addiction treatment and psychiatric programs," said Ken Tupper, a 36-year-old UBC PhD student who consulted on both reports. Tupper has been studying the cultural benefits of various psychedelic "plant teachers" for over a decade and co-founded TAMS in 2004.

Like many academics in this field, Tupper's interest in psychedelics started as a teen. "Curiosity led me to experiment and I found value through taking LSD and psilocybin," he said over mint tea at Blenz. "I started to see the cultural hypocrisy of our drug laws while caffeine, alcohol and tobacco were legal." Tupper went on to SFU to do a philosophy BA, then a master's degree in education where he researched "the value of psychedelic drugs. I thought I'd be laughed out of the room but they gave me a $5,000 fellowship to travel to Brazil and study ayahuasca."

Tupper took ayahuasca in ceremonial settings and said the experience changed his life. "Taking this difficult and unforgiving plant teacher has made me a more complete person," he said. "I compare it to rebooting your brain, and think our culture seriously needs that right now. We're at a crisis point and these substances could be used as cultural tools to shift consciousness and to bring people a greater connection to the earth, to animals, plants, the land. The war on drugs has intimidated academics for a couple of decades but we're seeing a re-emerged interest everywhere."

Interest in U.S.

The recommendations in the reports by the city of Vancouver and the Health Officers Council of B.C. have also turned on American researchers. "Those reports touch on the vanguard of treatment efforts with substance abuse and are a common-sense approach to drug abuse treatment and harm reduction," said Dennis McKenna, an ethnopharmacologist and psychedelic drug researcher based in Minnesota who plans to return to Vancouver to research Amazonian plants this September at BCIT. McKenna, a "child of the 60s," started sampling psychedelics in the Haight-Ashbury, area of San Francisco, then split for the Amazon to sample psilocybin with his brother Terrence, who detailed their trips in the book True Hallucinations.

McKenna moved on to the academic side of research at UBC in the early 1980s doing his doctorate in Botanical Sciences under Neil Towers. They were studying the genetics of psilocybin biosynthesis when Towers asked him if he'd be interested in going to the Amazon to study medicinal plants, particularly ayahuasca. McKenna responded, "My bags are packed. When do I go?" When he returned, McKenna landed a four-year fellowship researching ayahuasca pharmacology, then went to Brazil with UCLA-based Charles Grob to do a biomedical study of the safety of ayahuasca for the Brazilian government.

"Most of the people we studied were very dysfunctional before joining the UDV church: drug abuse, domestic violence, crime. But when they started drinking the tea in the ceremonial setting, it was like holding up a mirror to their lives. They literally changed their lives."

The researchers also found an intriguing bio-chemical marker in long-term ayahuasca drinkers. "It suggested ayahuasca may have reversed a neurochemical condition involving lower abundance of serotonin transporters that had been linked to alcoholism by other researchers," said McKenna, who acknowledges that further research would be necessary to confirm this, and notes that the UDV's "supportive social environment" was a factor in improved health. But the Brazilian government was impressed enough to approve ayahuasca for ceremonial uses.

The American government has been harder to persuade, but recently McKenna and his colleagues at The Heffter Research Institute have started various projects with psychedelics. Harvard researchers, meanwhile, are hoping to use MDMA to treat anxiety and pain in cancer patients. It's the first time academics there have tested the bureaucrats around psychedelics since Timothy Leary's infamous LSD experiments were halted by the institution in the early 60s.

A similar program is already underway at UCLA Medical Center, with psilocybin. And Johns Hopkins University just released a randomized controlled trial of the spiritual mind-expanding impact of psilocybin; one third of volunteers rated it the "single most spiritually significant" event of their lives. In South Carolina, psychiatrist Dr. Michael Mithoefer is using MDMA to treat post-traumatic stress disorder and depression.

'No money to be made'

Florida-based Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is helping various projects get off the ground. MAPS founder, Rick Doblin, said open-minded government bureaucrats are also helping to shift the tide. "Some good people got into positions of authority at the FDA and NIDA [National Institute of Drug Awareness] and have made a decision to back science instead of the war on drugs," said Doblin, acknowledging that another primary issue stalling research in the field is lack of industry funding.

"There's no money to be made from psychedelic drugs, so the pharmaceutical companies aren't interested. They like drugs that you have to take for your whole life and with psychedelic drugs you only need a few sessions," said Doblin, who completed a PhD at Harvard focused on the medical uses of psychedelics and marijuana.

Doblin's not shy about saying he takes psychedelics periodically at critical life junctures, like his 50th birthday. "Sometimes these experiences are really hard and force you to look at things you don't want to analyse about yourself," said Doblin. "They can also give you a sense of unity with the world that our alienating western culture doesn't provide. You realize you're not just isolated atoms floating alone so it gives very basic life-force connections. And the medical studies of benefits stand on their own merit."

MAPS is assisting the Vancouver Iboga Therapy House group to re-start its program to treat drug and alcohol addiction with the African shrub bark psychedelic. Though many of Marc Emery's initial ibogaine patients were unable to kick their habits long-term, Doblin is hoping to get funds for a long-term study of 20 ibogaine-using patients.

He said ibogaine was one of the most profound trips of his life. "I threw up for 12 hours straight and then I saw all of my worst flaws and hated myself, then became exhausted and had a beautiful night of bliss and self-acceptance," said Doblin of the experience. Other anecdotal reports of physical purging and psychological self-recrimination make it the kind of substance few people would dabble with recreationally.

Ayahuasca, known as the "vine of the gods" is a difficult plant teacher as well. Vancouver-born ethnobotanist Wade Davis described his ayahuasca experiences this way in his book Shadows of the Sun: "It is not necessarily, and in fact is rarely, a pleasant or an easy journey. It is wondrous and it may be terrifying. But above all, it is culturally purposeful." Ayahuasca's spiritual and cultural benefits, particularly for addicts, has been well documented and Vancouver-based non-profit group TAMS is advocating educational exchanges between local aboriginals and Peruvian indigenous cultures and hoping to open a centre on B.C.'s west coast. Ken Tupper is also just back from the second TAMS-organized workshop in Peru along with eight local "travellers" who attended ceremonies with master healer Guillermo Arevalo in the remote jungles. Their next 13-day excursion is planned for this fall.

Saskatchewan roots

The term "psychedelic" was actually coined in Saskatchewan by Humphrey Osmond, one of the first doctors to use LSD in the early 1950s at Weyburn Psychiatric Hospital. Osmond and his colleague Abram Hoffer (who still works out of Victoria and has just published his biography) treated alcoholics with LSD and their trials showed that a majority of patients kicked the habits after LSD treatment. Studying the effects of the drug also allowed Osmond and Hoffer to make a critical connection between mental disorders and neurochemistry; Osmond also sampled LSD and mescaline himself and arranged Aldous Huxley's first psychedelic trip.

Artists, academics, doctors, students, accountants and housewives around the globe were soon sampling psychedelics and by 1962 more than 1,000 articles had been published in medical journals about LSD alone.

But New Westminster-based Hollywood Hospital was the first clinical setting to use a laid-back beanbag chair-style setting for addiction treatment and the place became popular with celebs like Cary Grant, Andy Williams and Ethel Kennedy. It was even endorsed by the local Catholic church until LSD was criminalized, thanks largely to public hysteria around a handful of negative media reports as well as inhumane psychedelics experiments done by the CIA-backed programs like MK-ULTRA which was linked with researchers in the U.S. and Canada, including psychiatrist Ewen Cameron's infamous LSD experiments at Allen Memorial Institute in Montreal.

Today's researchers and advocates are necessarily cautious about the various ways these powerful substances could be used and potentially abused by big business, government, the tourist industry and psychiatrists. While neither the old-school flower-power advocates or the younger generation raised in the coke-fueled 1980s are booting around in painted buses, there is concern about the psychedelic experience becoming too clinical or consumerized.

"I'd hate to see it pharmaceuticalized: take two tabs and call me in the morning," said McKenna. "It can't be used as a shortcut to enlightenment. You also need to have a supportive community."

Danielle Egan is a regular contributor to The Tyee and writes for a variety of publications.

Related Tyee stories: Jeffrey Helm is writing an occasional series on brain chemistry and addiction; David Berner interviewed Vancouver Mayor Sam Sullivan and question his resolve on funding addiction treatment; and Angus Reid surveyed global opinion on drug policy. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: