[Editor's note: U.S. President George W. Bush said on Monday night that he will order as many as 6,000 National Guard troops to help secure the U.S. border with Mexico. The last time the U.S. stationed troops along the Rio Grande, a Marine shot and killed a Texas teenager within sight of his home. When Esequiel Hernandez Jr. died in 1997, he became the first American killed at home by U.S. troops since the massacre at Kent State University in 1970. This is his story.]

On the day he died, Esequiel Hernandez Jr. took his goats to the river. He led them from their makeshift pens, past the ruins of a Spanish mission, through an abandoned U.S. Army post and down a stony bluff to the Rio Grande.

When he reached the crest of the bluff, Hernandez stopped. Behind him lay the mud-red adobe homes and melon-green alfalfa fields of Redford. Before him stretched the Chihuahuan desert, Texas' vast gravel backyard, speckled with squat greasewood bushes and whip-like ocotillo plants. Except for Hernandez, whose goats brought him here each afternoon, the residents of his little oasis rarely ventured into this no-man's land.

On this day, Hernandez spotted something shaggy moving in the desert. He'd lost a goat not long before. He suspected wild dogs had taken it. He couldn't afford to lose another goat. He raised his ancient .22-caliber rifle and aimed at the creature.

Twenty minutes later, Hernandez's 18-year-old body lay grotesquely twisted across a stone cistern. He died trying to protect his goats. He was killed by a 22-year-old Marine trying to protect America's youth from drugs.

On May 20, 1997, Esequiel Hernandez Jr. became the first civilian killed by U.S. troops since the student massacre at Kent State University in 1970. His death led to a temporary suspension of military patrols near the U.S.-Mexican border. And in August, the government paid his family $1.9 million to settle a wrongful death claim.

Cpl. Clemente Manuel Banuelos became the first U.S. Marine to kill a fellow citizen on U.S. soil. Four investigations and three grand juries probed the May 1997 shooting. Each concluded that because Banuelos followed orders, he was innocent of criminal wrongdoing. Those who issued the orders were never tried.

Both young men became casualties of the Pentagon's quixotic $1 billion-a-year war on drugs.

Unready Marines

The mission of Cpl. Banuelos' to Redford began with a request from the U.S. Border Patrol. In late 1996, the Border Patrol approached a little-known military unit called Joint Task Force Six (JTF-6) about conducting an "observation post" mission along the Rio Grande. The routine request was quickly approved. JTF-6 put out a call for military volunteers, and the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force signed on.

Marine Corps Capt. Lance McDaniel arrived at JTF-6's El Paso headquarters in February of 1997 to begin planning mission No. JT414-97A. Four observation posts -- or "holes," as the Marines called them -- were to be established overlooking the Rio Grande at places where illegal crossings were common. Four-man teams would take turns manning the holes. During the nights, they were to radio reports of any illegal activity to the Border Patrol. During the days, they were to conceal themselves in a "hide site" just down river.

McDaniel picked Banuelos to lead one of the teams. The assignment was a coup for Banuelos, who had been not much older than Hernandez when he joined the Corps. Banuelos matured noticeably during his three years in service, earning an achievement medal rarely awarded junior enlisted men. And in the spring of 1997, while still a corporal, he had been selected to lead an observation team at Redford. All the other team leaders were sergeants. If the mission went smoothly, Banuelos would soon be a sergeant, too.

But mission No. JT414-97A was not going smoothly. McDaniel's efforts to prepare his men were hamstrung by bureaucracy and 1st Division command's view of the mission as little more than a subsidized training exercise. That's the conclusion of an exhaustive Marine Corps report by retired Maj. Gen. John T. Coyne, from which many of the details of this story were drawn. In one striking example, McDaniel's men were pulled away from a training exercise in order to participate in a dress uniform review.

Friendly fire

As a result of this type of bureaucratic interference, Capt. McDaniel conducted only three days of training before his teams departed Camp Pendleton for Texas.

Banuelos' men -- known as "Team 7" -- were among the least prepared: Cpl. Roy Torrez Jr., Banuelos' second in command, hadn't received any field instruction since basic training; his main job in the Marine Corps was driving a tow truck. Lance Cpl. Ronald Wieler also had received no field training since basic; most of his preparation consisted of cutting rags and sewing his own camouflage "ghillie suit." And Lance Cpl. James Blood, the team's junior man, didn't even meet his teammates until they arrived in Texas.

Late one February afternoon while McDaniel and JTF-6 were planning the Redford mission, Border Patrol agents Johnny Urias and James DeMatteo were patrolling the Redford riverfront. Eight hours west of San Antonio and five hours east of El Paso, Redford is one of the most remote towns in the United States. The adobe-and-cinder-block village stands in the desert above the muddy red soil along the river, every inch of which is planted in alfalfa, melons, pumpkins and other crops. Culturally, the village of 100 souls is more Mexican than American. Spanish is the language of choice. The nearest shopping center is across the river in Ojinaga, Mexico.

While walking among the cottonwood trees by the river, agents Urias and DeMatteo heard gunshots. They climbed back into their truck and drove up the dusty lane to the two-lane blacktop that winds through Redford.

Before they reached the village, a beat-up truck approached them from behind. It flashed its headlights. The agents stopped. So did the white pickup. A boy hopped out and ran up to the Border Patrol vehicle.

"I'm sorry that I was shooting," the agents recalled the boy telling them. "I thought someone was doing something to my goats. I didn't know you were back there."

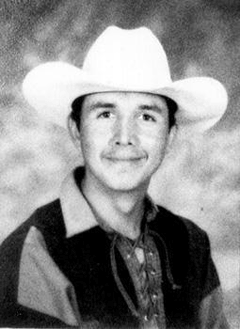

The tall, lanky teenager was Esequiel Hernandez Jr. Known as "Skeetch" or "Zeke" to his friends -- and simply as "Junior" to the adults in the village -- he was a popular kid who loved riding horses and dancing. A high school sophomore at age 18, the only visible indication of personal ambition was a large Marine Corps recruiting poster on the wall above his bed.

When he wasn't on horseback, Zeke helped tend the family's 43 goats. It was his chore to walk them to the river each afternoon. He usually took with him a World War I-era .22-caliber rifle his grandfather had given him. The old gun was mechanically unreliable, but straight shooting. This, too, he hung on the wall above his bed.

As the February sun crept behind the high, hard mountains, border agents Urias and DeMatteo studied the boy. No harm intended, they figured. No harm done.

Urias left the boy with a friendly warning. "Use more discretion when shooting your weapon," he later recalled telling Esequiel. "Especially at night."

Three days in the desert

Banuelos and his team were dropped off east of town late Saturday night, May 17. The Marines wore camouflage face paint and shaggy burlap "ghillie suits." They carried two five-gallon water cans, two radios and assorted gear. Each carried his own M-16A2 rifle.

Team 7 walked half a mile to the observation post. The team they were replacing was dehydrated and nauseous after its three-day tour. Banuelos, Torrez, Wieler and Blood settled into the stony bluff above the river. They saw two vehicles cross the river that night, and radioed the Border Patrol both times. As dawn came Sunday, Banuelos moved his men to the daytime hide site. The day passed slowly, punctuated by fitful naps.

The Marines had been warned to expect hostile drug smugglers. They were told that "the enemy" would employ armed lookouts. They were told that previous teams had taken fire. But no one told them about the goats -- or the boy who herded them.

The goats arrived in the afternoon. Dozens of them, scrabbling through the hide site, foraging among the greasewood bushes, hungrily eyeing the leaf-like ghillie suits.

Team 7 moved up to the observation post before sunset the next evening. The Marines reported several vehicles driving across the shallow river that night. But the Border Patrol only stopped one or two.

On Monday the desert became very hot. At mid-day, the surface temperature can reach 180 degrees Fahrenheit. Snakes stay in their burrows to avoid being cooked. The Marines had no burrows. They lay on hot stones, wrapped in their burlap suits. Each man had only three quarts of water per day. All they had to eat were fibrous goo bars called Meals Ready to Eat -- like Slim-Fast shakes without the liquid.

The goats returned in the afternoon. They stuffed their mouths with desert weeds. They gurgled as they drank deeply from the river.

By the second night, Team 7 had begun to realize that Redford was a heavily trafficked crossing, and that most of what was smuggled across wasn't drugs. Vehicles of every description arrived laden with tires, cement, furniture, produce and other contraband. Torrez and Blood griped about how rarely the Border Patrol responded to their calls.

"If they don't care," Blood recalled asking, "why do we need to be out here?"

Wrong place, wrong time

They didn't need to be there -- at least not in May.

A previous decade's worth of federal statistics proved it: More than 85 percent of all illegal drugs entering the United States arrived via official Ports of Entry monitored by the Customs Service. Most came concealed within legitimate cargo. Nearly all of the heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine shipped to the United States the year before Hernandez was killed flowed through official ports, according to federal estimates.

Marijuana was the exception. Half the weed consumed in the United States is grown domestically. Half of the rest comes across the Rio Grande at places like Redford. The Border Patrol was catching large loads crossing the river every fall. Marijuana is a seasonal crop; most of it gets harvested and shipped in the fall and winter -- not in May.

JTF-6 would have stopped more drugs from entering the country if its troops had been put to work searching the 3.5 million trucks rolling through the 39 customs checkpoints annually along the U.S.-Mexico border. But truckers were already complaining about the wait at customs. The corporations that hired them complained to Congress that more searches would undermine the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

Washington wants to stop the flow of drugs and immigrants, while increasing the flow of goods and services. The two objectives conflict. Putting troops in places such as Redford was a compromise. It allowed Congress to appear tough on drugs, while not hindering trade.

'Fire back'

Banuelos led his men out of the hide site early on the afternoon of May 20th, a departure from the mission plan. The Marines were hot, tired, hungry, dehydrated and still dressed like shrubs.

As they crept toward the evening post, Banuelos spotted a man on a horse on the Mexican side. The corporal put his team in a halt. Just then, Esequiel and his goats crested a small bluff. As usual, he was carrying the old rifle.

Banuelos whispered into his radio: "We have an armed individual, about 200 meters from us." A time-stamped recording of the radio traffic showed it was 6:05 p.m. "He's headed toward us. He's armed with a rifle. He appears to be in, uh, herding goats or something."

Hernandez saw something move in the brush at the bottom of the far ravine. He had bragged to friends and family members of what he would do if he ever spotted the wild dog he believed had taken his goat.

The goatherd may have fired once, as Banuelos and Blood claimed. (One spent shell was later found in the rifle.) Or he may have fired twice, as Torrez and Wieler recalled. Or he may not have fired at all, as the lack of gunpowder residue on his hands later suggested.

What is certain is that the four Marines believed they had been fired at by a drug smuggler.

Banuelos ordered his men face down on the hot gravel, then told them to "lock and load."

Hernandez stood on his toes. He peered across the desert. Torrez recalled the goatherd was "bobbing and weaving ... like when you look at something in the distance, you stand on your tippy-toes and try to move your head around to see."

At the operations center located 90 miles away in Marfa, Capt. McDaniel and his fellow officers immediately began debating what actions were authorized under the JTF-6 rules of engagement. But Banuelos knew nothing of this debate. At 6:11 p.m., he radioed: "As soon as he readies that rifle back down range, we are taking him."

Lance Cpl. James Steen, was manning the radio in Marfa. He replied: "Roger, fire back."

The command center exploded. McDaniel and the other officers believed Steen's authorization to "fire back" was wrong, according to written statements. Steen was pulled off the radio. A senior sergeant took the chair. But "fire back" was neither corrected nor withdrawn.

By this time, Banuelos and his team were atop a plateau about two football fields away from Hernandez. The Border Patrol had been dispatched, and Banuelos knew it. But for some reason, Banuelos kept moving his team closer.

The men slipped on the steep, loose gravel. Wieler didn't understand what Banuelos was doing. He said later that he "would have stayed and let the Border Patrol handle the situation." But he followed orders. The camouflaged Marines scurried forward one by one, crouching among the waist-high bushes.

At 6:27 p.m., Banuelos believed he saw the boy raise his old .22 and aim toward Blood. The corporal, an expert marksman, did not hesitate. He squeezed the trigger of his M-16A2. His bullet entered Esequiel Hernandez Jr. beneath his right arm. It fragmented and cut two trails through his chest, destroying every organ in its path.

Following orders

The Border Patrol arrived minutes later. Team 7 was driven back to Marfa, put in a motel room, given a six-pack of beer, and told to write statements. The story that emerged was that Banuelos was not "pursuing" Hernandez -- as specifically prohibited by the rules of engagement -- but was "paralleling" the goatherd out of fear that the boy was running a "flanking maneuver."

The Texas Rangers investigated the shooting. The Justice Department investigated the shooting. JTF-6 investigated the shooting. And the Marines investigated the shooting. All concluded that Banuelos followed orders.

A county grand jury refused to indict Banuelos on criminal charges. A federal grand jury refused to indict. And a second county grand jury, given substantially more evidence than the first, also refused to indict. All concluded the corporal had committed no crime.

Banuelos was under investigation for more than a year. But the orders that sent him to Redford in May, the orders that put him in the field with an under-prepared team, and the authorization to "fire back" -- these were never put on trial. By agreeing to pay the Hernandez family $1.9 million, the Navy and the Justice Department effectively closed the most viable legal route through which those decisions could have been questioned.

Human rights activists fear the settlement will clear a political path for JTF-6 to resume armed border patrols, which could lead to more deaths. In a response to the scathing Marine Corps report, Gen. C.W. Fulford Jr. lamented Team 7's lack of training, but noted that even the best trained Marines would have shot back.

"Indeed," Fulford wrote, "it is probable that a superbly trained team of infantrymen would have immediately returned fire."

Clemente Manuel Banuelos is no longer a member of the Marine Corps. His promising military career died the same day Hernandez did. The 23-year-old now struggles to support his young wife, Luz Contreras, in their modest Southern California home. He is looking for work.

Rounding up the goats

On the day Esequiel Hernandez Jr. died, his father brought the goats back from the river.

Hernandez Sr. was chopping wood when he saw the crowd of Border Patrol agents, sheriff deputies and other authorities gather on the hill across from his adobe home. He drove the old pickup over to see what was happening.

Not knowing who he was, a deputy sheriff asked whether Hernandez Sr. might be able to identify the victim. The old man stared curiously at the Marines, still dressed in their ghillie suits. The leather-faced father was then shown the lifeless body of his son. He wept, and wailed, in Spanish.

The sixth of eight children of Maria de la Luz and Esequiel Hernandez Sr. had been 18 years old for six days.

The Hernandez family was kept away from the scene that night. Pushed back by sheriff's deputies, sobbing family members shared their grief and anger within the privacy of the Hernandez rancheria.

Later, the old man went down to the river to round up the goats. Ten-year-old Noel went with him. After the goats were put away, Noel marched into Esequiel's bedroom and tore the recruiting poster from his dead brother's wall.

Monte Paulsen is a contributing editor to The Tyee.

This report was originally published in San Antonio Current in 1998 and was drawn from two months of interviews in Texas and Washington, D.C. Those interviewed included the Hernandez family and their Redford neighbors, as well as officials of Joint Task Force Six, the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Border Patrol, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency, congressional aides, drug policy experts, military policy experts, lawyers and reporters. Clemente Manuel Banuelos declined to be interviewed.

Many of the details described in this account come from official documents. These include statements and testimony collected by the Texas Rangers, the Justice Department and the Marine Corps. The facts presented in this story were either agreed upon by first-hand observers or were independently verified. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: