Just before 7:30 on the morning of Sunday, March 31, I opened my laptop, checked my mail, and found a note from Google Alerts saying two people in Shanghai had died of bird flu.

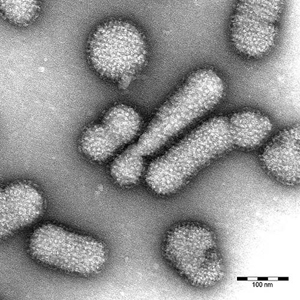

But this was not the H5N1 bird flu I've been blogging about for eight years; this was something called H7N9. Influenza has many different strains -- so-called "swine flu" is H1N1 -- but this was the first time anyone had ever been infected with this strain, much less died of it.

This kind of story doesn't happen often in the strange online world of Flublogia, where people share news of diseases outbreaks, public-health problems, and the medical consequences of political decisions. The last time was almost exactly four years ago, when H1N1 came out of nowhere as an aggressive and fast-spreading disease that turned into a pandemic.

That one email about H7N9 effectively hijacked my blog. Hours earlier, I'd been covering dengue, the novel coronavirus out of Saudi Arabia, malaria, and the mysterious appearance of thousands of pig carcasses in Shanghai's Huangpu River -- disastrous for the people involved, but nothing out of the ordinary.

This was different, even if only three people had contracted this kind of flu and two of them had died. That was how H5N1 had started in Hong Kong back in 1997, with a disease we'd never seen suddenly sickening and killing people. Once again a virus had figured out how to infect a "naive" population. Like Aztecs facing smallpox, we have no immunity to H7N9.

Early warning under pressure

The outbreak also reminded everyone of SARS, which in 2003 had come out of China and swept from a Hong Kong hotel corridor right into Toronto. That wasn't a flu; it was a coronavirus, and since last summer a novel coronavirus has been popping up in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states, and as far north as Germany and Britain.

So the appearance of this new virus was of instant interest to the global health community, and it was also a major test of the worldwide early-warning system that has emerged since H5N1 and especially since SARS.

In 1997, the web was a primitive medium; no one knew where anything was, and browsers offered a random website if you didn't know where you wanted to go. By 2003, blogs were providing a lot of guidance. I discovered that some were dealing entirely with SARS -- and doing so far faster and more thoroughly than the newspapers and TV could.

By the time I started my blog H5N1 in 2005, as an attempt to educate myself, the blogosphere was enormous and still growing. I found myself part of a community of interest -- experts, journalists, and laypersons like myself -- willing to share information. That community has grown ever since, greatly enhanced by Twitter.

Everyone understood back then that networks like Flublogia could play a part in gathering and disseminating information about disease outbreaks. But would they do so reliably?

Some of the early flu forums fell apart in personal feuds. Some bloggers were manifest cranks, looking forward to the next pandemic as if awaiting the Rapture. Others assumed that any government would suppress the truth, and sometimes they were right. China had famously done so for weeks about SARS, and the UN still tries to evade responsibility for bringing cholera to Haiti in 2010.

A snap quiz in communication

So here was a snap quiz on what governments and the blogosphere could do, whether in cooperation or in conflict, to determine the nature of a new disease and to inform the world about it. So far, we all seem to be passing the quiz.

The Chinese authorities have come in for criticism over their slowness to report H7N9; the first cases in Shanghai started in mid-February when an very old man and his two old sons came down with what seemed like pneumonia. The old man and one son died, but only the father was eventually confirmed to have H7N9. The surviving son has reportedly refused to be tested again.

By the time other cases began to turn up, in March, they were scattered across a wide stretch of eastern China -- not just Shanghai, but a city in nearby Anhui province and several other cities in Zhejiang and Jiangsu provinces. It understandable, then, that the Chinese health experts took a while to recognize what was happening, and then reported it some six weeks after the first case in mid-February.

Since then, however, the reports seem to have been coming reasonably promptly. Dr. Jody Lanard, a U.S. expert in crisis communication, has criticized the Shanghai authorities for "mega-confident over-promising" about fighting H7N9. But she praises the Chinese Centres for Disease Control "for early reporting and non-over-reassurance." She also notes an "astonishing" Xinhua editorial with a "bold critique … I assume this is being done with the blessing of the government."

Others have not been so complimentary; the South China Morning Post has published a compendium of media reports from across China that generally criticize the official response.

Hazards of the echo effect

Apart from offering insights into modern China's public health system and press freedom, the online response to H7N9 also shows itself to be far from perfect. Someone tweeted on April 6 that a person from China had arrived infected in Hoboken, NJ, of all places. Cooler heads on the #H7N9 hashtag quickly stomped it out, but it showed how easily nonsense can compete with fact.

More serious, from my point of view, was the "echo effect": Stories go out all over the world and are published everywhere from Hong Kong to Buenos Aires. But by the time aggregators like NewsNow and Google News display them, many are already out of date.

Flublogia obsesses over the very latest reports and the most recent case and death counts. So which story is correct -- the one with five deaths or the one with six? I finally put together a timeline of cases, just to keep the story straight in my own mind. But it means daily or twice-daily updates, plus endless vigilance about the dateline of every story.

Working with the grownups

More encouragingly, the online media have been increasingly accepted by those I call the "grownups" -- the virologists, epidemiologists, and experts in agencies like WHO and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. This is true even of the Chinese CDC; though its English-language page is often out of date, its Chinese H7N9 coverage is pretty current and open to Google Translate's rough efforts. WHO is tweeting its H7N9 announcements even before posting them on its website, and WHO media head Gregory Härtl is a frequent tweeter as well.

This is a remarkable change from the days of SARS and even of H1N1, when such agencies showed a bureaucratic fear of the web in general and social media in particular. Like their political masters, the bureaucracies fear embarrassment more than any pandemic, but they are now willing to get out there and make their case in 140 characters or less.

I suspect they are beginning to realize that in the social media their expert status is enhanced, not threatened; a solid, factual tweet will be re-tweeted around the world before the rumour can get its boots on.

Similarly, mutual support is developing between bloggers and mainstream journalists; our posts and tweets often tip them off to new stories and information sources, and their stories give us much-needed context and background -- and sometimes correction.

We do not have a technofix for the threat of future pandemics, but we do have a better structure for alerting the world's public health systems -- and the publics they serve. It's rewarding to be part of it, and very much worth the occasional shock on an early Sunday morning. ![]()

Read more: Health, Media, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: