When one tires of hearing about humans and the problems that we’ve created for ourselves, it’s refreshing to think about something else. Another consciousness that doesn’t share our obsession with Twitter, real estate or American politics.

For that, there’s nothing quite like a good animal story. In recent months there’s been a bushel of them, a menagerie of feathered, scaled and horned narratives that offer not only relief from humanity’s self-obsession but also beauty, pleasure and something of the awestruck.

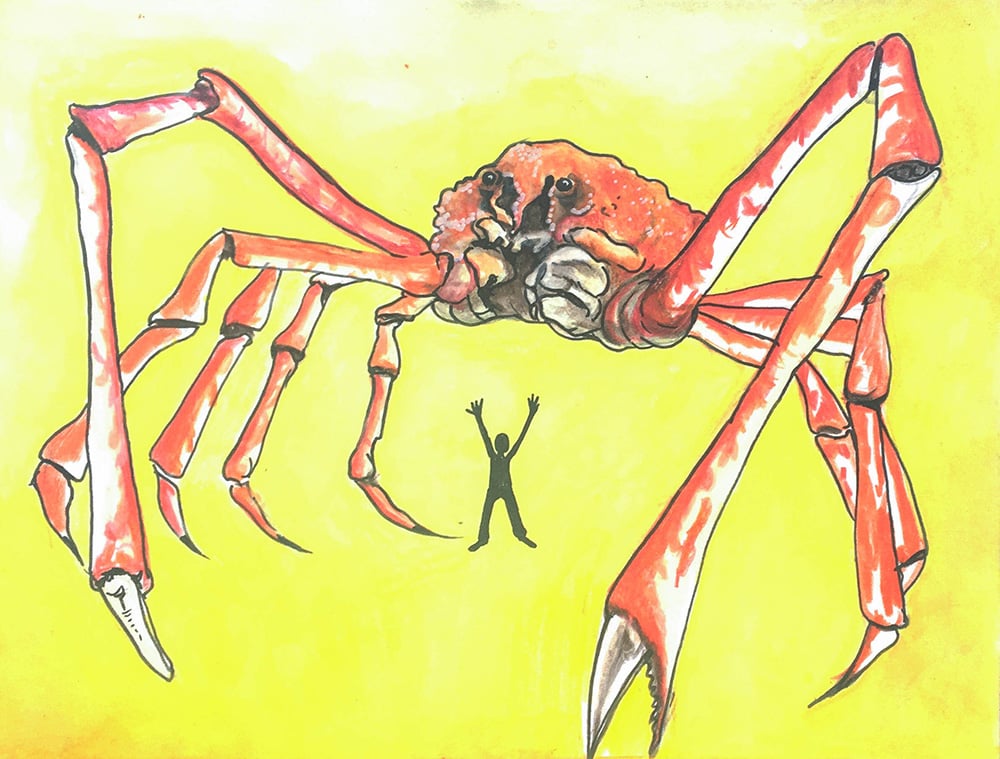

Who needs science fiction when there are things like a glow-in-the-dark platypus or a Japanese spider crab? When I stumbled across an image of a man holding up a spider crab to provide a sense of scale, I got so excited I wanted to rush out the door and find someone to tell.

A particular kind of giddy joy attends discoveries like a new species of whale or that octopuses communicate with colour.

The most recent thing to blow my mind was the fact that when hermit crabs go looking for a new shell and find one that’s too large, they’ll line up beside the shell and wait. As subsequent crabs come along and try it on, they all line up in descending order of size until finally, when a crab that finally fits the shell arrives, they all swap shells down the line, so that everyone gets a new home.

Learning this, I actually yelled out loud “WHAT?!” If hermit crabs can practise socialism, why can’t humans?

My habit of looking to animals for escape, curiosity and a strange collectivist instinct sprang from an early immersion in the books and stories of Gerald Durrell. The British naturalist cut his teeth on the island of Corfu, documenting his collecting trips as well as the beastly behaviour of his close relatives in My Family and Other Animals.

Detailed in language rich and heady, Durrell recounted his early experiences stalking tidal pools, streams and meadows for especially alluring specimens of flora and fauna. The book is lush, teeming with precise details of colour, shape, size and habitat, all of it captured with the fevered glow of youthful passion, bordering on obsession.

Any mention of an interesting animal story and this species of passion comes flooding back, pushing aside any mundane stuff and striding onto the scene all aglow with tails, tentacles, fur and scales. I’m sure I’m not alone in saying, “I do not wish to hear anything more about American politics, but do tell me about the Fraser River white sturgeon.”

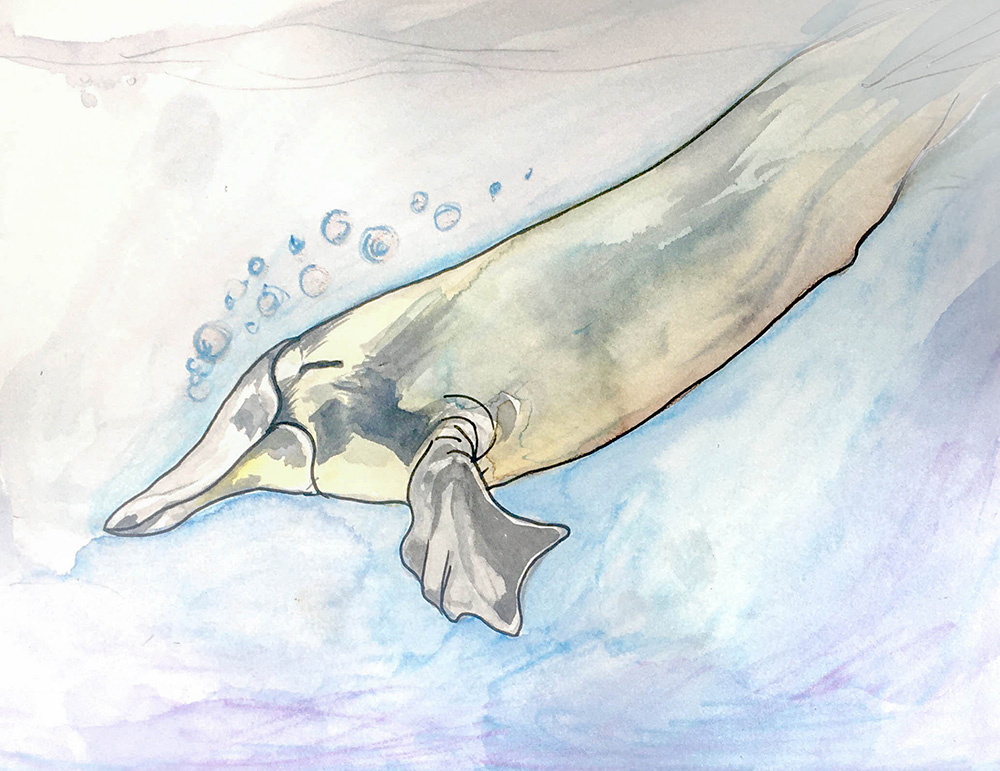

Did you know that sturgeon date back to the Triassic period, 200 million years ago, carrying the weight of history in the plated shields that line their backs? These dinosaur fish have been mucking about on river bottoms for millennia, reaching lengths of up to three metres and spawning legends along the way (oh hello, Ogopogo).

But they’re still little understood. Even the name is something of a misnomer. White sturgeon aren’t one colour but varying shades of cream, mauve, pale yellow and burnished grey. The elaborate designs of their armoured plating are so lovely they could make Charles Rennie Mackintosh jealous.

Attempts to rebuild the population have stumbled over the fact their reproductive habits are somewhat mysterious. The number of breeding adults in the Fraser River is still perilously low, despite concentrated efforts to bring them back. Sturgeon reach sexual maturity at a relatively late age for fish. Adult males spawn every one to two years, and females seem even less interested. How can we make these fish hornier, cry the scientists! More sexy research is needed.

The next time you’re tempted to order calamari, think about the fact that squid and octopuses are some of the wildest animals on the planet. The more one learns about them, the more fascinating they become. While the recent Netflix smash My Octopus Teacher may have garnered greater attention, our tentacled friends have been doing miraculous stuff for a long time.

Assessing the true level of cephalopod intelligence, however, has been difficult, because they refuse to co-operate with human experiments. “Unruly” is the word used by Peter Godfrey-Smith in his book Other Minds to describe the octopus approach to research projects.

They are supreme escape artists. With half a billion neurons, about the same as dogs or a three-year-old child, stories about their tricksy ways are legendary. They can recognize individual humans and often spit water at those that they don’t like.

Smith’s work predates My Octopus Teacher by a number of years, but both offer a vision of a creature so unique and strange that humans are hard-pressed to comprehend them. Most of their brain power is situated in their arms. It’s akin to humans having 2,000 fingers, as the film states. But in spite of our differences, we share one remarkable thing.

In a Guardian interview about his book, Smith explained: “A camera eye, with a lens that focuses an image on a retina — we’ve got it, they’ve got it, and that’s it.” Cephalopods and humans are the only two creatures on the planet that share this feature. When you stare into the eyes of an octopus, it stares back.

What does it mean? I don’t know! But it’s wonderful.

A return to the deep wonder of other lifeforms can be strangely liberating when human drama gets too much. Even the most common and humble creatures can deliver profound surprises.

With this I give you Gunda, the lowly sow who’s the star of director Victor Kossakovsky’s extraordinary documentary. The film is a document of life, the nitty, gritty and shitty of it, on an anonymous farm in Poland. A pig’s life isn’t the only one on display; there are also cows, chickens and the ordinary hum of insect and plant life. All have their own issues to contend with.

The most remarkable thing about Gunda is that it gives farm animals a measure of selfhood and individuality. This is a long and venerated tradition of animal stories. Anyone who grew up reading Charlotte’s Web, Old Yeller, The Yearling or Black Beauty will remember the great yodelling, anguished sobs that attended these books. In essence, life is tragic kids, so get used to it.

I avoided watching Gunda for a long time because I was scared to feel those feelings again. It’s interesting that some people will happily watch films where their fellow sapiens are hacked to pieces, but they’ll turn tail and run from any film that depicts animal suffering. Empathy is a strange beast. But to deny animals the truth of their own emotions, pleasure, pain, even dreams, is to cut ourselves off from our own fully-embodied place in the world.

In Gunda, humans are not in the picture. Animals exist in all of their ordinary, otherworldly beauty quite apart from us. Luminous is a word seldom used to describe pigs, but that is exactly what they are — glowing, gorgeous and lit like Ava Gardner. With her distended teats and huge lamp-like ears, Gunda might not seem like a movie star but she is, and like any star she makes us see her and feel her, her care and love for her children, her frustration, impatience and, yes, her terrible awful grief.

Often in films that purport to celebrate other forms of life humans insert themselves into the story, hogging all the attention. Documentary and narrative films are equally guilty of this. To have humans simply absent in Gunda comes as an incredible relief. And really, maybe that’s what we’re looking for when we look to animals — some means of escaping our obliterating, overwhelming narcissism.

Human hubris makes us think that there’s only one species on the entire planet. The truth is that we share it with billions of other creatures. Unless they have a vested interest in us, like mosquitoes or tapeworms, they mostly leave us alone. The same can’t be said for humans: whether assaulting poor innocent manatees or shooting giraffes, we’ve tangled with almost every other planetary inhabitant.

Notably, sometimes when humans depart an area, the animals move back in. As a recent article shows, in Europe species that have not been seen for 150 years have remerged and are sauntering down the empty streets of abandoned towns and villages.

This kind of resurgence, almost more than anything, gives me hope. Now, please tell me more about the Humboldt squid. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: