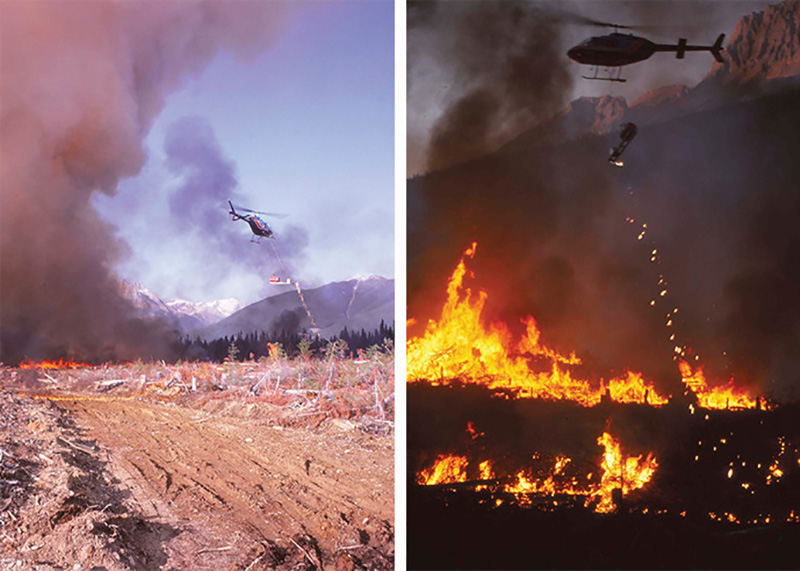

[Editor’s note: Slashburning is the practice of setting controlled fires to clear away leftover timber material to reduce fire risk to forests and communities. We are excited to publish an excerpt from Nick Raeside’s 'Slashburner: Hot Times in the British Columbia Woods' — a first person account of the people who make their living doing this dangerous job — which is out next month.]

In North America, fire was used by early settlers as a cheap and effective way of clearing land. Sometimes it would prove to be a little too effective, as was the case in Vancouver in 1886, when a fire set for this purpose got away and burned down much of the town. The BC Forest Service, created in 1912, was responsible for ensuring that such unfortunate events weren’t repeated. But fires were still used for clearing purposes. It had become obvious that accumulations of woody debris left behind after logging operations posed a significant fire risk. The first recorded deliberate burning of such material in order to reduce the hazard took place in 1913.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the steam donkey engine made industrial logging on a large scale possible. There were some unfortunate side effects, though: sparks produced by these engines would cause accidental fires in the woods during the summer months. This happened in 1938 on Vancouver Island, resulting in the Bloedel Fire, which blackened nearly 75,000 acres. A major factor contributing to this fire’s size and severity was the thousands of acres of slash that had accumulated after years of logging. As a direct consequence of the fire, Section 113a of the BC Forest Act came into effect the same year. This legislation made it obligatory for logging operators to dispose of the logging slash they created by burning it in the fall, to prevent accumulations from becoming a summer fire hazard. This law was directed at operations taking place on the B.C. coast and Vancouver Island, and it wasn’t until 1967 that Section 116 of the above act extended this requirement to the rest of the province.

Logging practices were changing by the mid-20th century, and better utilization of the forest crop left less flammable waste. It was also becoming evident that burning this waste could sometimes be detrimental to the forest’s ability to regenerate if the fire was so hot that the soil underneath was cooked. Fire started to be used rather more scientifically as a silvicultural tool; however, the burning of logging slash still involved an element of risk, as the unfortunate residents of a small community near Salmon Arm discovered in 1973 when an escaped forestry burn ran through their properties.

Wildfires that take place during the summer get a lot of media coverage, particularly when property is lost, which has unfortunately been the case a number of times in the last two decades. The majority of the public may be unaware, however, that, at least in prior years, once the upheaval of the summer wildfire season had ended, a program of deliberate fire lighting for forest management purposes would begin. Even as smoke from wildfires still lingered in mountain valleys in various parts of the province, some fire bosses became burn bosses and prepared to generate a lot more smoke. And while many firefighters greeted the arrival of cooler weather with relief as they looked forward to well-earned days off, there were others who couldn’t wait for the fall slashburning program to begin. Possibly it was the prospect of a few more weeks of employment that appealed to many, but there were a few who rather enjoyed the irony of being paid to set fires in the woods.

There have been some exceptionally good fire bosses in the BC forest fire control business, and I’ve been privileged to have met one or two of them. There have also been some who were not so good, and possibly there are certain individuals who would place me in the latter category. I’d put myself somewhere in between, all things considered. I probably would have taken the prize for the worst-dressed fire boss if there’d been such an award, however, and I’m fairly certain that I’m the only one to have shown up on the fireline barefoot.

At least I can say that nobody was killed or seriously injured on any of the fires and slashburns I was responsible for. In hindsight I have to admit that was possibly due to good luck as much as good management, as things did get a bit weird occasionally. Safety on the fireline was at the front of my mind most of the time, but it did get pushed aside now and then by an irresistible urge to liven things up a bit. I’ve always believed there’s room in every workplace for a few practical jokes, even though some of my former employers haven’t always agreed.

The events in this book took place exactly as described. It’s been a long time since I last saw the areas we burned, but I understand that the forest is growing back quite nicely.

This excerpt was taken from 'Slashburner: Hot Times in the British Columbia Woods' by Nick Raeside, with permission from Harbour Publishing. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: