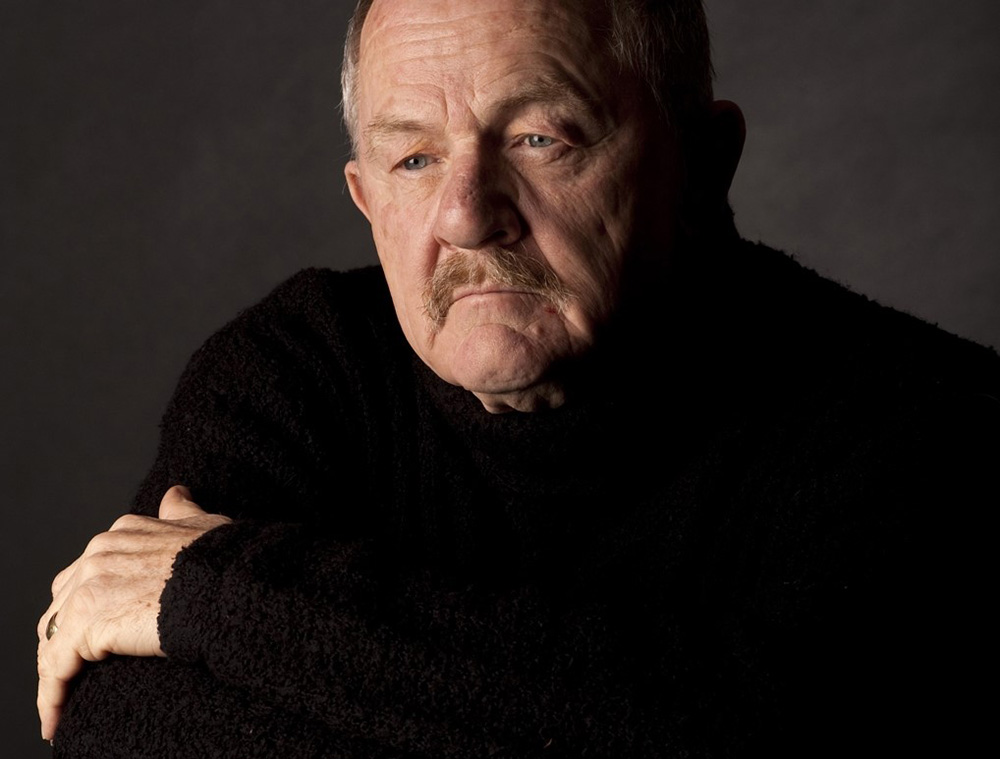

[Editor’s note: Patrick Lane, the award-winning Canadian poet, memoirist and novelist, died Thursday, March 7 after a long illness. In 2008 he published a novel that offered a window into the rough world of B.C.’s interior towns that shaped his coming of age. His interview with The Tyee from that year we republish here.]

For more than 40 years, Patrick Lane has been one of Canada’s premier poets. With severe honesty, the Saanichton resident’s award-winning work has chronicled the struggles of British Columbia and its people, gradually assaulting romanticized portrayals of the province. But with the publication of his immensely disturbing first novel, Red Dog, Red Dog, Lane has dropped an atomic bomb on the British Columbian consciousness. His fiction is an eruption of the brutal, repressed history of the Okanagan Valley in the 1950s.

“It was a very violent world back then,” Lane recalls. “Yet as a society we’ve chosen to forget.”

Red Dog, Red Dog centres around the Starks, who Lane establishes among literature’s most dysfunctional families. Large sections of the novel are narrated from beyond the grave by Alice, one of three daughters who have died as an infant from Mother Stark’s neglect. The father is an abusive, amoral drunk who roams the house at night with a loaded shotgun. Lane surrounds the family with an Okanagan town populated by sadistic police, savage drug dealers and apathetic killers. Although at times the extreme natures of the cast seem unconvincing, their deformities are endlessly intriguing.

The title’s red dogs are the two red-headed Stark brothers, Tom and Eddy, the novel’s main characters. Both brothers live under the weight of profound trauma: Eddy suffering the memories of Boyco, a juvenile prison, and Tom suffering the secret of an ugly deed he performed too young. “The trauma of the brothers is like the trauma of the town,” says Lane. “They can try to repress it, but the more they repress, the worse it comes out.” While Eddy spirals into a life of drug abuse and random violence, Tom finds himself increasingly demented, seeking salvation in a place where, as Lane says, “tragedy cannot be prevented.”

Although Eddy’s hideous behaviour — burning buildings, poisoning dogs, robbing houses — frequently steals the spotlight, Tom Stark is the fuller character, caught up in a paradoxical love and revulsion for his family. “Tom doesn’t comprehend Eddy’s behaviour any more than the reader,” says Lane, “but he cannot help but love him. All of the people he lives with are monsters, but he loves the monsters deeply.”

Lane has similarly conflicted feelings toward the Okanagan Valley, where he grew up. He describes his childhood as “surrounded by violence,” yet his novel’s lush imagery exhibits feelings of great tenderness for the landscape (a valley is described as “a dress thrown off, unfolded at her feet.”)

Lane believes we can come to terms with the violent origins of society and ourselves. “If you can find yourself inside this novel,” Lane says, “even if the characters are monsters, then I’ve succeeded.” In a conversation at the Wedgewood Hotel in Vancouver, here is some more of what Patrick Lane shared...

On the removed bubble that was the Okanagan:

“The setting of the novel, the place I knew, was 1958. At that time, the Okanagan Valley was only 75 or 80 years old. The valley I go to now, I don’t recognize. The new valley has 600,000 people in it. When I lived there, they were small towns, very isolated. We had practically no access to the outside world. When the rest of the world was going nuts over the Cuban Missile Crisis, I missed it completely. When JFK was assassinated, I didn’t hear about it for three days. The Vancouver Sun came in a train overnight, so you always read about news that happened at least two days before. In a sense, you lived outside of history in the interior of B.C.”

On burying inconvenient truths:

“There was a vast part of the population that lived in a lawless world. When I lived in North Thompson, I worked First Aid in a small mill town. One day an old remittance man died of alcoholism. I remember going down to the mill, and told them he had died, and that it should be reported. And someone replied, ‘Why? I don’t want police in my town.’ So we buried him. That’s what we did. We picked up the body, went over to the town dump, dug a pit and buried him. End of story. No one reported it. No one wanted police in the town.”

On growing up with violence:

“Because the valley was still in the mentality of the village, rather than the global village, people treated each other at times with great affection, and at times with immense violence and hatred. There’s a boy in the novel who is made to kneel on dried peas and read the Bible every Sunday. I remember a boy like that growing up. His father would make him kneel on dried peas. It’s terrifyingly painful. I remember trying it, because I was a bit of a funny kid and wanted to know what he was experiencing. I tried it for about five minutes, until the pain was so terrible I couldn’t bear it.

“When I was six, my six-year-old friend was murdered by his father. He was beaten to death. His father had a ritual: he would beat him every Sunday on the grounds that the boy might do something bad that week. I would wait for him outside the shed while his father beat him half to death, and then we would go play.

Finally the boy died. He was buried with a funeral, but no one investigated it, there were no charges laid.

“Violence was so common you didn’t think about it. Violence happened all around you. It fascinated me, and I was intrigued by it. In my world, it was normal, but I knew at the time that it was not normal, and it deeply disturbed me. That knowledge came from reading. I grew up reading, so I had a grasp on a fictional world that told me there were intolerable behaviours. But if I had grown up reading the Bible, I would have read of societies in which such behaviour was tolerated.”

On being unprotected, but unafraid:

“We live in a kind of paradise out here on the West Coast, protected from violence. But I’ve never in my life known a society so full of fear.

“Believe it or not, we weren’t afraid back then, even though there were no laws, and if there were, people didn’t pay attention to them. I didn’t grow up protected, but I didn’t grow up afraid. When I was seven, my mother would give me a peanut butter and jam sandwich at seven in the morning and tell me not to come home before dinner. Then I would take off.

“I knew who the pedophiles were in town. There was Sam the Candyman, he always had candy. You could always get candy from Sam, you just wouldn’t go home with him. Sam would say, ‘Why don’t you come back home with me?’ and I’d say, ‘I don’t think so, Sam. Give me some candy.’ The more protected children are, the less knowledge they have about the world, and the more vulnerable they are. The violence of the world I grew up in was a great teacher.”

On how stories shape society:

“One of the theses of the novel is how memory affects us, how storytelling shapes us. When we go into the past, we find who we are as people, villages and countries. Stories are our foundations. And when you investigate our stories, you find that it’s a history of violence — hundreds of years of monstrous inequity — and yet as a society we’ve chosen to forget our stories, even though we’ve built society upon them. This leads to a terrible denial. When we lack understanding of our stories, nothing ever changes.”

On the sober task of publishing his first novel at the age of 69:

“In 2001, I came out of a treatment centre for drug and alcohol addiction. I wanted to start writing again, but I was afraid of writing poetry, and I was afraid of writing short fiction. I’d done them both before, and I was worried, now that I was sober, that I wouldn’t be able to write anymore, that somehow my writing and my addictions were tied up together. So I thought I would find a safe place to write, and that was non-fiction, which I’d never really written. I began by writing about my garden, from month to month for a whole year. But that began to transform itself, areas of my own past began to creep in. This became the memoir I published (There Is a Season).

“The memoir was two years’ work, and when I finished that I was on a roll. Writing long, expansive prose pieces becomes an addiction, the very act of writing, so I kept going.... I began looking at old, old stories I’d written 10 or 15 years ago, and found an unfinished piece I hadn’t been able to resolve in the form of a short story. It was about a three-day party I went to as a teenager, with all the typical drugs, booze, rape and pillaging. When I read it, I realized it could become a novel. I built from there, and it turned into Red Dog, Red Dog.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: