- Canada in the Great Power Game 1914-2014

- Random House Canada (2014)

With the guns of August 2014 rumbling in Ukraine, Gwynne Dyer's latest book is a timely review of Canada's role in the past century of war and peace since the outbreak of the First World War. It throws a disturbing light on what we did and why we did it.

Dyer actually begins his narrative 15 years before the start of the First World War, with Canada's involvement in the Boer War (1899-1901). The country was barely three decades from Confederation, small but growing rapidly through immigration, and still very much a British colony. English Canada was just that, a population with a high proportion of recent immigrants from Britain.

Quebec was still a church-dominated, ill-educated island of francophones. (Dyer wryly observes that Quebec's Roman Catholic hierarchy dealt with English Canada on the principle of "You look after your empire and we'll look after ours.") But Quebec did not identify with the British Empire or British political concerns -- nor with France. If anything, they identified with the Boers, European-descended farmers who were being taken over by the Brits.

So the South African contingent had few French Canadians. English Canada's soldiers acquitted themselves reasonably well, but failed to understand why Britain had recruited them in the first place. Dyer argues that Britain already foresaw a major European conflict. After a century in which no great power had gone to war against another great power, some kind of clash was inevitable and so was British involvement.

A Polish banker, Jan Bloch, had recently published a major study of modern warfare. With eerie prescience, he warned that no great power could survive an industrial war against its equals without economic ruin and revolution. Britain military thinkers didn't quarrel with that, but decided that the reservoir of wealth and manpower in the Empire would help Britain survive a Blochian war of attrition.

A precedent for future wars

Britain needed the precedent of colonial involvement in imperial wars -- not to deal with the Boers today but to deal with the Germans tomorrow.

In this the Brits succeeded brilliantly. If Canadians identified with the Empire, they would not pause to ask whether a European war was in their own best interests. After all, Canada was safely remote from any military threat except that of the Americans. Whether Britain, France, Germany or Switzerland dominated European affairs would mean nothing to us.

But we bought the imperial con game, and thereby set our course for the following century -- including relations with Quebec and with the United States.

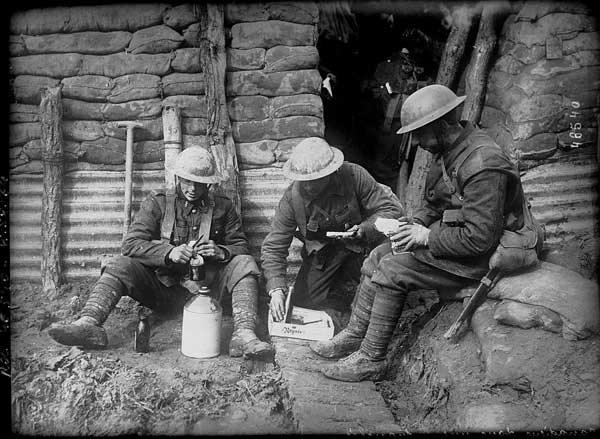

Dyer argues persuasively that Quebec felt little need to go to war in 1914. The vast majority of volunteers were recent British immigrants. By the time they had been fed into the meat grinder of the trenches, few remaining young men were willing to follow them.

This resulted in a shock that launched Quebec separatism and actually determined Canadian foreign and military policy all the way to Afghanistan. Conscripting Canadians into a war would be politically disastrous if those Canadians saw the war as no threat to their own nation and refused to be drafted. That was very much the case in Quebec, but English Canada had already put too much skin in the game. Anglophones began to see francophones as disloyal slackers.

Something more subtle was at work here beyond "with us or against us." As the carnage continued, it could no longer be justified as just politics by other means. Once upon a time, wars were strictly a matter of the national interest, but it was in no nation's interest to sacrifice its youth in meaningless slaughter.

A battle of good against evil

War became a battle of good against evil, and of course we were the good guys. The deaths had no other justification. This theological element has persisted through countless wars in the past century, right up to war against the evil-doers in Afghanistan and now the U.S. air attacks on the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.

This is why every Canadian town has a cenotaph to its war dead. It's also why the first Canadian anti-war novel wasn't written until 1930. Its author was an American, Charles Yale Harrison, who'd fought in the Canadian Army. Canadian reviewers viciously attacked Generals Die in Bed, precisely because it questioned the sanctity of the war.

Sanctity was all very well for Remembrance Day ceremonies, but Canadian politicians like Mackenzie King were both scarred and scared by the political consequences of the First World War. Like King Pyrrhus after beating the Romans, they knew that "Another such victory and I am undone." You could rally good against evil, but if good suffered too many casualties, you'd be out of office in the next election. And your country might then shatter like the Austro-Hungarian, Russian and Ottoman empires.

Fighting a low-cost war

As a result, when the Second World War arrived, King was quick to find Canada a role that would not cost too many lives. Commonwealth pilots got their training in Manitoban skies, and then flew in vast bomber raids against Germany. The bombing cost many airmen's lives, but infantry pay the real price, and they were safely stashed in Britain until D-Day.

So Quebec tolerated a death toll that could have been far worse, and when King eventually brought in conscription, he drafted "zombies" -- soldiers who would not be forced to serve outside Canada. Then Canadians got involved in the conquest of Italy and the carnage increased, in part because we'd put so many Canadians into the air force and had no trained infantry left. Throwing the zombies into the meat grinder wasn't even militarily useful; commanders in the field would still rely on their experienced soldiers, not on terrified kids.

While holding seances to consult with the spirits of his dead mother and Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Mackenzie King somehow got us through the war as a political unit. Whether in the air, on land, or at sea, we were a force to be reckoned with. But somehow we had shifted from following British military strategy to following the Americans, without ever pausing to reflect on what our own national interests might be.

Better said, we knew those interests required a very small military, all of it stationed at home. But even after demobilization we had a military and government that had spent six years in the "Big League," as one general called it. It was exciting to be on the inside of a new military-industrial complex, playing with the newest weapons and theoretically influencing the world's new superpower.

Falling out of step

So for no valid reason, we fought in Korea and stationed troops in Germany as insurance that when the Soviets came, we'd be committed to fighting them. Not until Vietnam did Canada fall seriously out of step with the U.S., and Jean Chretien kept us out of Iraq (despite opposition leader Stephen Harper's protests) because the Americans' lies couldn't persuade the UN Security Council to authorize George W. Bush's war of choice against Saddam Hussein. But the price was sending Canadians to their deaths in the UN-approved war in Afghanistan.

We signed on to the Cold War and its improvised aftermath the Great War on Terror, and we still pay the price. The North American Air Defence Command, designed to stop Russian bombers, was obsolete as soon as the Soviets had nuclear missiles in the late 1960s. But it still operates. NATO has also outlived its anti-Soviet usefulness, but finds new jobs for itself (and us) far from the North Atlantic. Putin in eastern Ukraine is just the latest evil-doer to warrant spending blood and treasure in the cause of good.

Gwynne Dyer makes his case calmly, factually, and with his trademark dry humour. Having served in the Canadian, British, and U.S. navies, he knows whereof he speaks -- unlike the war pimps who infest Canada's op-ed pages.

Much of his book, he tells us, is based on material for a 1980s TV series that CBC cancelled after his series "The Defence of Canada" raised just these issues. That's not surprising. Just as the Soviet Union was imploding, we and the U.S. were both spending more than ever on our armed forces. The Berlin Wall fell, the USSR vanished, and the spending went on.

It had to; evil is always out there somewhere, and big militaries need big budgets for the next big threat. ![]()

Read more: Federal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: