Apparently, the Ian Wallace panorama in front of me at the Vancouver Art Gallery is huge. Word is that it depicts the long golden grasses, cliffs and ancient oaks of Hornby Island's Helliwell Park. I am told Wallace hand-painted black and white photos and then super-imposed his friends in an old school kind of way onto that landscape. It sounds cool. But I can't see it.

I can't see it because my eyes are clamped shut as part of a non-visual tour of art that I can't touch or hear either. But maybe I will feel it.

Meanwhile, on this day in February across town, PuSh Festival performers are taking blindfolded audience members on 2.5 hour tours of hidden Vancouver. Diners are sitting down in the pitch black of Dark Table to taste a meal they can't see.

And in the Okanagan, vision-impaired and blind artists from New York, Europe and B.C. are showing their visual art at the Kelowna Art Gallery. They can't see the art they made for others to see.

What am I not seeing? Is there a growing movement among artists to downgrade vision, to knock it off its pedestal at the top of the hierarchy of senses? Not to mention the hierarchy of art?

Are they suggesting that we see better when we can't see?

The excitement of closing one's eyes

A lot of people are thinking about these things now, says Carmen Papalia, the Vancouver-based contemporary artist who developed the non-visual art tour /pilot project I am on at the VAG as a way for sighted people to stop relying on their eyes to see.

"Non-visual experience can be revelatory, it can be exciting, it can be interesting and I feel we have so few opportunities for non-visual interpretation," he says.

Papalia lost his sight 10 years ago at 21, but gained a new appreciation for other ways of seeing the world.

"I had to immediately switch from visual learner to non-visual learner," he says. "And I felt that both experiences were equal and relevant and valuable. If I could be a non-visual learner it would be valuable for others to be non-visual learners as well."

An art lover, Papalia had to rely on the descriptions of his friends to experience art as his vision failed.

"They would tell me details about things that were around and they would frame my experience. Eventually their descriptions became the art itself," he says. "This is a different way of experiencing art. It's a really engaging way of experiencing art."

Realizing this spurred a desire in him to engage the public in an exploration of how we access the world. What are the various ways we can exist in a place? Sighted, blind, young, old, art-educated and not.

As essentially egocentric beings, people tend to see the world only through their own filters, he concluded. If they could see through his filters, it might change the way they think about access.

"They might realize that they have the agency to change access, or take advantage of access not taken advantage of often," he says adding that participants of the non-visual tours, titled See For Yourself, he has offered at galleries such as the Portland Art Museum, the Columbus Art Museum in Ohio and the Vancouver Art Gallery say it transformed the way they saw the spaces.

"I feel that having people experience a non- visual approach for a prolonged amount of time has been working to change people's perceptions," he says.

'Vision is personal'

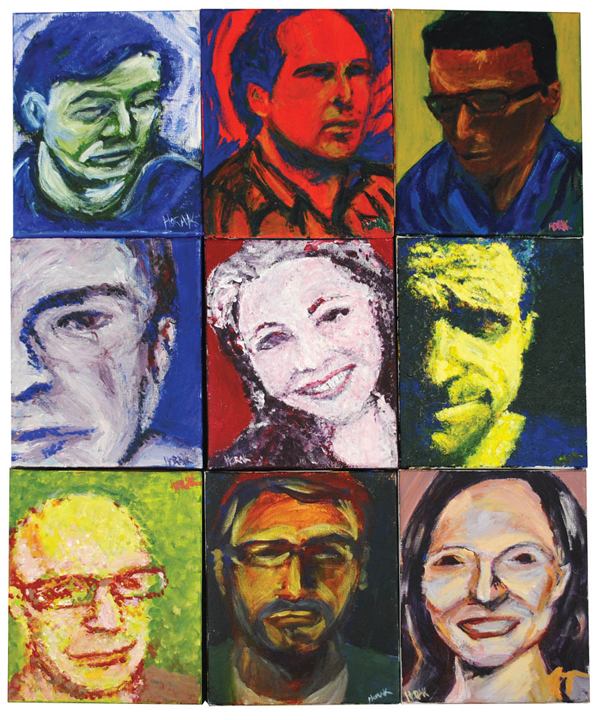

Actor, director and producer of live theatre Bruce Horak has lived well with nine per cent full vision his entire life. He recently picked up a paint brush to create portraits of people as he sees them. He is one of the artists showing at Kelowna Art Gallery.

"Vision is very personal," he says. "The eyes are just a conduit. How you interpret what you are seeing is all happening in the brain."

Artists have always strived to show us that we all see the differently. Horak is no different from the cubists, surrealists or abstract painters in that effort. He hopes his art will shift the viewer's perspective of the world and for a moment take them out of themselves. "To see that there is a new way to look."

Horak sees as though through a straw. At the end of that tunnel vision is a fuzzy, coloured light that forms an aura around objects and people.

When he paints a portrait, the aura and the conversations he has with his subject influence the image. But there is more to it than that. After the painting is done, Horak has the subject don his +12.5 prescription glasses, close their right eye and hold the painting very close so that they can see it the way Horak does. He hopes it creates a sort of metaphorical 3D effect.

"Here is my image and here is the way you see it and maybe by putting those two things on top of each other, you get that sense of dimension. That depth."

"The Kelowna gallery [exhibit] is pretty cool," he says, "but it is actually missing one element which is to sit, have your portrait done, have the conversation and actually experience the art through my glasses."

France-based choreographers Martin Chaput and Martial Chazallon explored the idea of seeing without seeing with their PuSh Festival dance performance called Do You See What I Mean.

As dancers and choreographers, they wanted their PuSh audience to explore how they alter the environment and how the environment alters them. They theorized that being blind-folded would bring that notion into focus more profoundly than with sight.

"It's a way of having them relate to their environment differently," he says. "Instead of sitting watching a performance we have them in motion and blind folded."

"We are not trying to put people in an uncomfortable place for the sake of it, but for them to achieve a more of an intimate space. It is about the way they experience the environment. We are interested in their perceptions. It's about seeing without seeing."

Chazallon says that as participants get used to sightlessness they enter a new relationship with their environment.

"It is a very interesting, very profound, very rich relationship to your surroundings and to others," he says.

Is it more rich?

"No I don't think so. It is just different. But it is very unusual for a sighted person so it becomes very rich."

Having performed this dance in cities around the world, Chazallon and Chaput have seen that once people open their eyes, the blind experience sticks with them. It opens them to a fuller, deeper experience with their worlds, one that uses all the senses.

Blindfolded

Back at the VAG I feel in good hands with my guide Susan Rome, the gallery's program coordinator of schools and docent training. As part of the gallery's pilot project, Papalia trained her to give non-visual tours. With her hand on my elbow, she guides me through the spaces I have been scores of times, but have never experienced like this.

At the Helliwell panorama, she walks me the length it so I get a sense of its size. She tells me what I would not have readily seen even with my eyes open.

For one thing colour photos this large were impossible to print in the 1970s. Wallace had to print 15 black and white panels himself, then hand-paint them and put them together to create one panorama. For another, the people in the image are Wallace's friends and they had never been to Helliwell Park. They posed in Wallace's studio.

I know Helliwell Park and imagine the scene. I put my own colours to it, my own people. When Rome explains the people in the image were initially glued on, I imagine a thin outline around them to separate them from the landscape. It creates a 3D effect in my mind's eye. "Cool," I think.

Later, I look at the image on the gallery wall and don't see the 3D effect. But it doesn't matter that what I imagined is different from what Wallace produced.

It isn't what Papalia sees either. By using our imaginations, we have become participants in the art rather than simply viewers and the art gains a dimension.

"It is not the art on the wall anymore, it's the art they have imagined," says Papalia.

Similarly, Chazallon says the PuSh tour integrates the audience perspective into the art so that it becomes a negotiation between the guide, the artist and the audience.

"Being blindfolded you still picture things," says Chazallon. "And that vision, those images, that imagination exists for everyone. That is a very interesting area for us. Taking away the sight gives us a new pathway to see something. It doesn't deny a pathway."

Rome, meanwhile, is also seeing the exhibit with fresh eyes. Although she is very familiar with Wallace, as guide she notices new details each time. She too is participating in the art and gaining new perspectives.

Vision does need to be knocked down a peg or two, says Papalia. Our reliance on it limits our ability to see as clearly as is possible, to feel the experience in a more full-bodied way. But nobody is suggesting we should all poke firebrands in our eyes.

Papalia hopes that closing our eyes will open them to the value of our other senses and to the disability society foists on the vision-impaired when it relies on visual presentations. He wants galleries to include more senses in their presentations of art because he believes this would enrich the experience for the vision-impaired and more importantly for the sighted.

Horak, meanwhile, would love see like others. Blind his whole life, he would love to have full vision. But only temporarily, so that he can see through others' eyes the same way they can use his art to see through his.

"I would love to have full sight, but I wouldn't want it forever," he says. "Just to see what that would be like. Then go back to what I have. I wouldn't trade it. It is what makes me who I am."

The Just Imagine exhibit at the Kelowna Art Gallery is on until March 17, 2013. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: