The sight of entire families wandering around downtown Vancouver decked out in every possible permutation of Olympic-style clothing, grandparents to babies emblemized from stem to stern, everyone glassily smiling like they have drunk deeply of the Kool-Aid. Brrrrr.

Forgive me, but I find this type of rabid boosterism unbecoming to Canadians.

In the lead up to the Games, it was fine to bitch and complain, but now if you say anything bad about the Olympics in mixed company, people look at you like you might bite them. But even if it can seem as if the entire city has pretty much rolled over and let the Olympics have its way, there are still pockets of good old-fashioned Canadian contrariness. This resistant spirit is exemplified by two documentaries (Reel Injun and Salute) opening this week and next. Hail Mary, and pass the popcorn, you can hold the ammunition for now.

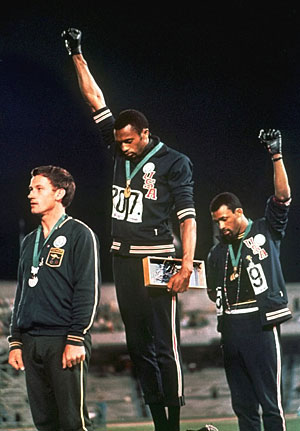

DOXA Documentary Film Festival's Moving Pictures sports series wraps up with a bang next Thursday Febr. 25 with a screening of Salute. The film centres on the iconic image from the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City when three men took to the podium to receive their medals for the 200m. Two of the athletes, Tommie Smith and John Carlos, raised their fists into the air, while the third wore a button for Project For Human Rights supporting their cause. Two of the men were black Americans and one was a white Australian by the name of Peter Norman.

When you witness an act of courage, it is a rare and singular thing. It's little wonder that the image of black fists raised in silent protest still reverberates some 42 years later.

Paying the price for protest

Salute, directed and produced by Peter Norman's nephew Matt Norman, lays out the context for the event in detail, systematically explaining that protests in 1968 were happening all around the globe: from Australia, where the burgeoning Aboriginal Rights movement was echoing the Civil Rights movement in the U.S., to France, where student protests prompted a nation-wide strike. Into this highly fraught moment dropped the Olympic Summer Games. Perhaps it was destiny that these three very different men were fated to be standing on the podium at that particular time and place. Or as Peter Norman says, "Maybe we were all put on this Earth to do just that."

The one thing that the film makes explicitly clear is that there was a very large price to be paid for speaking out. In the case of Norman, whose time in the 200m still stands as an Australian record, the cost was exclusion from all Olympic activities until the day he died. Despite being one of the fastest men in Australia, Norman was not allowed to compete in the 1972 Summer Games. Even in the 2000 Summer Olympics held in Sydney, Norman was shunned by organizers. Both Tommie Smith and John Carlos suffered even greater levels of retribution, one man even losing his wife to suicide. But the fact remains that despite death threats and worse, this trio of men had the courage of their convictions and the strength of character to speak out.

Before his death in 2006 from a heart attack, Peter Norman gave an interview to The Daily Telegraph about the need to speak up and out: "Today there is a whole new generation, but someone still has to stand up and make a statement on behalf of the down-trodden... Once you've earned the right to stand on that podium, you've got that square metre of the world that belongs to you. What you do with it is up to you -- within limits."

Seizing the spotlight

In this most current incarnation of the Olympics, it's hard to imagine any contemporary athlete getting up on the podium and taking such a principled stand. Although gag orders were supposedly issued to different Olympic teams during the Beijing Games, even wearing the colour orange (as a symbolic gesture of solidarity with Tibetan monks) proved difficult. Athletes these days all seem content to toe the party line, smile sweetly and wait for the endorsement deals to roll in.

Getting up and telling the world that there's something you don't like, or something you want to change, doesn't come around too often, but it usually seems to starts with an O. The Olympics or the Oscars, for example.

The Oscars also have had their fair share of disruption, but none so remarkable as Marlon Brando and Sasheen Littlefeather's speech at the 1973 Academy Awards Ceremony. The Native Rights movement, like the Civil Rights Movement before it, was at a watershed moment, with the standoff at Wounded Knee. Not permitted to give the whole of Brando's prepared statement, Sasheen Littlefeather was booed by audience members and had to be protected from the fury of a very drunk John Wayne. The entirety of Brando’s speech can be read here.

Seeing is believing

In his film Reel Injun, about the depiction of native people on film, Cree director Neil Diamond details the Oscar event, as well more than 100 years of cinematic racism, beginning with Thomas Edison and ending with Kevin Costner. One of the film's saddest stories concerns native actor Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance, who committed suicide rather than have his black ancestry exposed. In the 1930s, being native still had some romance and exoticism attached to it, whereas being black could get you killed.

One of the central ideas in Diamond's film is that people often believe what they see in the movies. Reality is not a patch on the big screen. Reel Injun demonstrates just how ubiquitous and common the misrepresentations of First Nations dress and clothing were in Hollywood films. The adoption of the "Indian" headbands, for example, came directly out the need for stuntmen to keep their wigs on while shooting Westerns. But in amongst this collection of white actors in red face, and Sicilians pretending to be native elders, something rather remarkable emerges, the means of resistance and telling your own stories endures. The representation of First Nations people didn't really change until First Nations filmmakers made their own films, from their own perspective. In this, the power of image is more than a means to rectify history, it is about creating genuine identity.

Wearing your politics

In the context of the Olympics, the role that images and symbols play has also become extremely explicit, whether that means decking yourself and your entire family up in clothing from the HBC, or pulling on a balaclava. Given that this is supposedly the most First Nations-friendly Olympics, from the opening ceremonies to the medals to the road signs on the highway up to Whistler, all state that this event has been granted the support of the First Nations people. If the black power salute at the 1968 Games silently screamed defiance, does the adoption of First Nations symbols speak to acceptance or capitulation? No matter how much First Nations pastiche they stick on top of the games, the Winters Olympics is still pretty white, despite the fact that Russian skaters, Oksana Domnina and Maxim Shabalin supposedly intend to perform in red face with their so-called "Aboriginal dance'" routine, which captured them the European ice dance championships. Even while protesters chant "No Olympics on Stolen Land!", and First Nations people stage a hunger strike downtown in protest, the games roll on.

Whether you believe that the First Nations' role in these Olympics is about cooperation or cooptation, there is money being made. Buffy Sainte-Marie, performing at the Four Host First Nations Pavilion after the opening ceremonies, said in an interview with the Province: "It's corporations who take too much from the land, and governments that let them, who want to divide us. But this is a time for us all to come together." Yes, we've supposedly all come together -- under the banner of Cola-Cola, RBC and the Hudson's Bay Company -- but a little voice inside my head keeps chanting, "Don’t drink the Kool-Aid..."

It will be interesting to witness the massive hangover that happens after the big O party is over, when the good people of Vancouver wake up with terrible sugar headaches, coated to the skin in fading logos and facing a mountainous pile of debt that would make any skier blanch whiter than the non-existent snow. ![]()

Read more: 2010 Olympics, Film

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: