[Editor’s note: This article runs in a new section of The Tyee called ‘What Works: The Business of a Healthy Bioregion,’ where you’ll find profiles of people creating the low-carbon, sustainable economy we need from Alaska to California. Find out more about this project and its funders.]

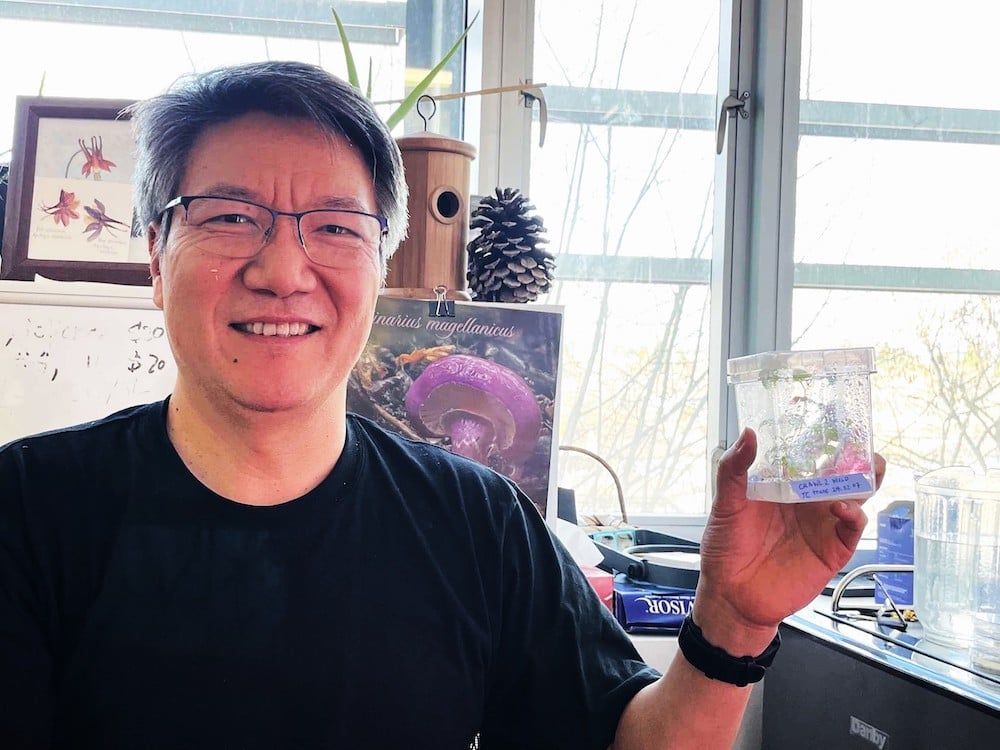

During the summer of 2016, Ji Yang was somewhere between Squamish and Vancouver when a vine twisting through underbrush and bushes caught his trained eye. The plant had clusters of cone-shaped flowers with hues of vibrant green and hints of yellow, and it exuded a floral scent. Yang, a biologist and botanist, had discovered a feral hop population growing in the wild, and he was intrigued.

Already familiar with the long history of hop farming in B.C., Yang gathered as many of the plants as he could into bags and brought them back to the biology labs at Langara College, where he works, to study their genetic makeup.

“I said to myself, ‘I wonder if they would make good beer,’” recalled Yang, who is a microbrew enthusiast.

Yang took his question to chemist Kelly Sveinson, head of Langara’s Applied Research Centre, and they decided to collaborate in finding out. “I thought it was a brilliant idea,” said Sveinson, who secured a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada to launch the work.

Today, the feral hops project, a bustling outfit based at Langara College in Vancouver, is identifying new feral hop varieties to create distinct regional beers. It has the potential to change B.C.’s local beer economy, which currently relies heavily on the United States for its hop supply.

Growing conditions are becoming harsher every year due to climate change. In 2023, Canada experienced its hottest year ever recorded. Temperatures rose up to 2.3 C warmer than the average temperatures throughout the seasons, making conditions difficult for the few Canadian hop farmers trying to cultivate their crops.

Higher temperatures can adversely affect hop cultivation by hindering the formation of their cones and reducing the available time for the cones to properly develop. Feral hops cultivated in B.C. provide an opportunity to localize production, reduce the industry's carbon emissions and preserve biodiversity, all within a tiny, climate-resistant bud.

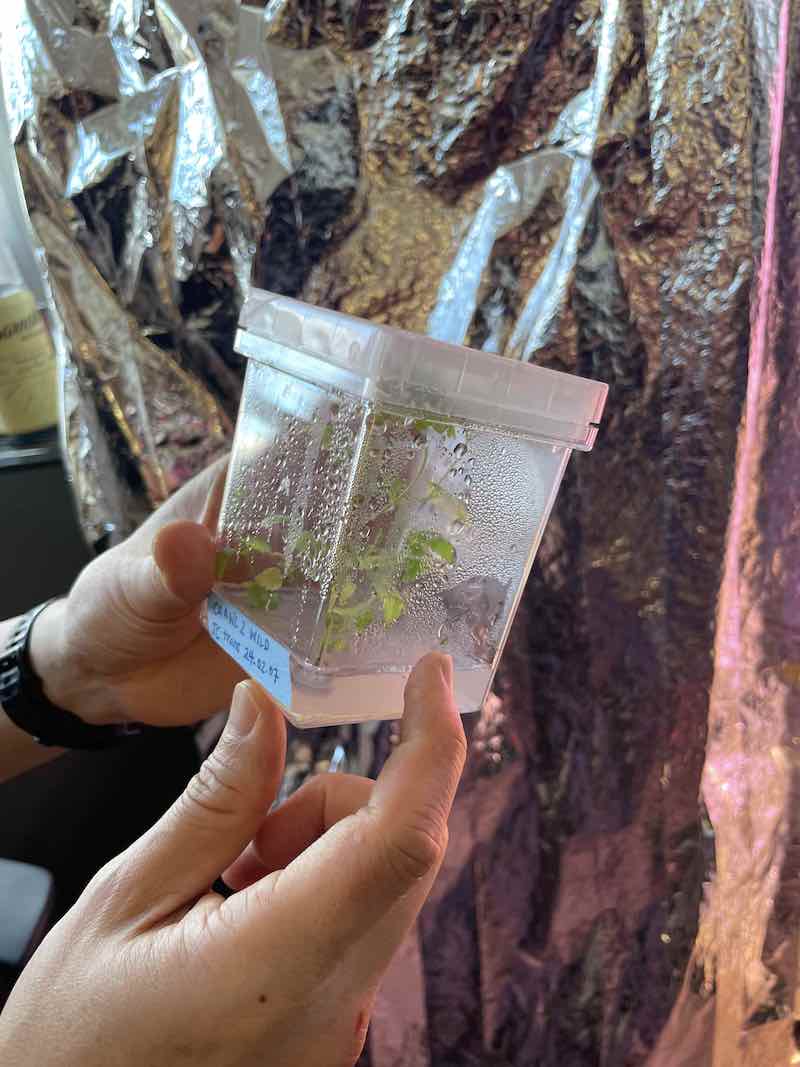

Last year Yang and students taking part in the feral hops project discovered that because feral hops have grown independently without human intervention, they may have become resistant to the region’s plant diseases and changing weather conditions. The team is also at work cultivating their own crops of feral hops. The plants are propagated based on the tissue culture method, which starts with taking small apical samples of a plant’s tissues.

These plant tissues are then surface-sterilized to remove contaminants, then placed in a tissue culture container and kept in a growth chamber for two to four weeks.

The samples with rooted tissues and healthy leaves will be planted in Perlite Sphagnum soil before being transferred to larger one-gallon pots.

When the plants have grown strong enough, they can be planted at a hop farm.

Yang said that during this process the team unveiled some unique characteristics of the feral hops.

“They’ve learned to handle possible droughts, which would do well in places like the Okanagan and Fraser Valley,” he said.

In an era of rapid climate change that features severe seasonal droughts, he believes this discovery will enhance the sustainability and climate resiliency of the hop and brewing industry.

Despite the surge in the number of craft breweries and hop farms on the West Coast, the beer British Columbians like to savour cannot be considered entirely Canadian.

The American company Yakima Chief Hops has been patenting the most popular strains of hops in Western Canada since 2010. Before that, B.C. breweries were turning to the United States in the 1940s to source their hops during the rise of "macro brewing," which refers to large-scale beer production by major corporations. As a result, many of the province’s previously thriving hop farms shuttered in the latter half of the 20th century.

B.C.’s hop farms reached their peak production between the 1940s and 1950s when about 1,600 acres of farmland were dedicated to producing the crop. The Fraser Valley was one of the largest hop-producing regions in Canada at the time.

As of 2020, a steep drop in B.C. producers has left only 10 to 15 hop farms collectively growing 200 acres of hops. Only five of those farms are producing commercial-grade hops, according to Crescent Island Farms.

Back in the Langara lab, the team was tasked with finding a farm that would agree to grow their hops and discover what flavour profiles, or terpenes, they could produce. Terpenes are natural compounds found in hops that give beer its signature flavours and aromas, such as a citrusy kick or spicy aftertaste.

In 2022, Yang attended a conference hosted by the BC Craft Brewers Guild, where he met Ken Malenstyn, who wears many hop-related hats. He is the chair of the BC Hop Growers Association, founder of Crescent Island Hops and co-owner of Barnside Brewing in Delta, B.C. He helped open Barnside Brewing beside his nearly 10-acre hop farm in Delta in 2019 in an attempt to create a truly farm-to-table beer.

Malenstyn said he was interested in the idea Yang had brewing.

“The brewing industry is very competitive,” said Malenstyn. “There are about 240 active breweries [in B.C.] right now.”

Due to its competitive nature, he said, the brewing industry has reached a point of saturation. But limited shelf space means companies are often fighting one another to be featured in liquor stores where "big beer" dominates.

At its core, Malenstyn said, the feral hops project fit seamlessly into his own vision at Barnside to create a hyperlocal beer — something he’s been doing for years now.

“Our product is not an amalgamation of mass producers, and a lot of craft beer, unfortunately, is,” said Malenstyn.

He said the new hop varietal from the feral hops project could empower brewers to become more environmentally sustainable and cost-effective.

Buying products from local sources instead of mass distributors can reduce distribution costs, lower carbon emissions and boost the profits of brewers and hop farmers who work and live locally.

“I think with this, we are going to see more of an uptick with using local ingredients if we can convince other breweries to take on that model,” said Malenstyn.

With resources from Barnside Brewing, the project was able to progress. Malenstyn has been growing Yang’s plants on his farm since 2022. Last year, he finally discovered what these hops are made of.

“We’re at a stage now where we’ve got some winners,” said Malenstyn. “Now, we’re trying to propagate those same plants on a larger scale through commercial acreage.”

The winners Malenstyn is referring to are the particular characteristics in hops that can make a beer taste hoppy and have a floral smell. This means that the terpenes within the hops can be used not just for making India pale ales, or IPAs, but also for other types of beer in need of a hoppy flavour and floral aroma — to create an entirely unique flavour profile.

Malenstyn said the distinctive branding and cost-effectiveness behind the feral hop project have driven its profitability.

Scaling the project at this point requires more propagation to brew the beer on a larger scale. The team has made an India pale lager — a type of beer that combines the hoppy taste of an IPA with the smooth finish of a lager — from the hops, but Malenstyn said it’s not quite ready to be sold commercially.

“We want to get to a stage where we can do more brewing trials now that we know this model works,” said Malenstyn. “It will take a year to sell it commercially.”

Yang, Sveinson and Malenstyn have also partnered with Josh Mayich, the owner and operator of Island Hop Co. on Prince Edward Island. The business invested in the feral hops project as a commercial partner to observe if the hops can thrive in weather patterns like those on the East Coast.

“This is a model we could apply to anywhere in the world,” said Malenstyn.

Malenstyn assigned some of his brewers to help with the feral hops project. Longtime employees Justin Larter and Calum Huntington have helped harvest and brew a brand new beer. In September 2022, the first batch of beer was tasted among the staff with Yang and Sveinson at a tasting party.

The beer was made using the wild hops from Yang's lab and was named Tamarack. Barnside Brewing created an India pale lager using these hops.

“I’m biased, but it was good,” said Yang. “We see viability with this beer, and I believe Ken will make more come this September.”

The project has been successful thanks to the careful research and chemical discoveries of Yang and Sveinson. The farm and distribution expertise of Mayich and Malenstyn has only added to its success, proving its potential in marketability and profitability.

Highlighting the regional terroir of feral hops is creating a strong sense of place among brewers, hop farmers and consumers.

So far, the project has appealed to hop-growing companies across Canada and stimulated an increase in consumer engagement at Barnside Brewing. Malenstyn attributes this to the growing interest in authentic, locally sourced ingredients.

Breweries like Barnside have also capitalized on the narrative of discovering and utilizing feral hops, which has fostered more consumer loyalty, translating into increased beer sales.

Yang said the project is less about money and more about creating something uniquely Canadian.

“I think it’s important to preserve biodiversity in this era of climate change,” he said.

Yang said his research has highlighted that the hops he has developed are viable and possess valuable weather-resilient properties.

To make the most of the resiliency of his newfound hops, Yang said, they can be used for crossbreeding with other hops already on the market to create a new range of enhanced, hybrid hops.

This could be a significant step forward for the brewing industry, he said, as it may lead to the development of hops able to withstand the impacts of climate change.

“We’re working towards a more sustainable system for everyone involved, because if the hops are doing well, it means the brewing industry is doing well,” said Yang.

“And that's what we want to see.” ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Food, Science + Tech, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: