The Tyee.ca

During the global economic boom of the 1990s, 54 nations in the world actually got poorer. Large corporations have amassed huge profits at the expense of underprivileged nations. Globalization has forced millions of third world workers to become economic slaves to western corporations. Consumers in developed nations only see the final products of globalization and not the process it takes to achieve them.

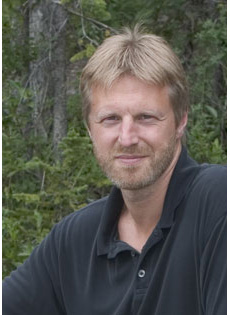

Hugo Bonjean is a former executive with an international hotel chain who came face to face with extreme wealth and extreme poverty existing side by side when he spent several years working in South America. His experiences led him to question how corporations do business in the global economy. The result was a book called In The Eyes Of Anahita published in October by Synergy Books and Eagle Vision Publishing Ltd.

Bonjean is now head of The Company Coach, a leadership development company. He lives near Calgary, Alberta, and I caught up with him while he was on a tour to promote his new book.

“We need to change the charters of corporations,” Bonjean said.

Originally, corporate charters were considered a privilege and their operations had to be of benefit to society or their charter could be revoked. Corporations have since been given the rights of personhood and permitted to live indefinitely.

“Many now believe the purpose of the corporation is simply to benefit shareholders,” Bonjean said. That is the argument made by the popular documentary film The Corporation, and the bestselling companion book. The Corporation author Joel Bakan, a UBC law professor, writes that by their legal nature corporations, like psychopaths, are incapable of altruism, or even taking responsibility for damage they inflict unless it harms their profitability.

Business leaders tend to colour the creature differently. “The corporation is nothing more than a social contrivance that enables people to cooperate,” Fraser Institute executive director Michael Walker told BC Business magazine, adding that “the corporation reflects all the wonderful and not-so-wonderful features of human behavior.”

‘Triple bottom line’

Bonjean admits restoring the original purpose of the corporation could be decades away.

“We want entrepreneurship,” Bonjean said. “But there has to be social and environmental accountability. Right now, corporations are externalizing those costs.”

Socially responsible stockholders could drive the process. “Perhaps more attainable is the goal of triple bottom line accounting,” Bonjean said. “Some corporations have already embraced that system.”

The triple bottom line focuses corporations not just on the economic value they add, but also on the environmental and social value they add – and destroy. At its narrowest, the term is used as a framework for measuring and reporting corporate performance against economic, social and environmental parameters. At its broadest, the term is used to capture the whole set of values, issues and processes that companies must address in order to minimize any harm resulting from their activities and to create economic, social and environmental value.

“A corporation is just a piece of paper, but people act on its behalf,” Bonjean said. “If the corporation is not ethical, people in the corporation are not ethical. People say, ‘This is just business, it’s not personal.’ Tell that to a Colombian coffee grower.”

Bonjean believes that things are beginning to change.

“I see some companies that are making real commitments,” he said. “They are finding that they can focus on quality, educate their customers, pay $12 an hour wages to produce clothing and still make a profit.”

Where are the churches?

The U.S. is the eight hundred pound gorilla. “This can’t happen unless consumers and investors at the grassroots level in the United States get on board,” Bonjean said.

He is surprised that churches aren’t assuming moral leadership.

“It’s astounding how many churches there are in the U.S. and Canada, more than just about anywhere,” Bonjean said. “But their values and practices tend to diverge. The key value seems to be money. Where in any religion does money appear as the prime value? It has to be more than just a Sunday thing.”

Bonjean has faced his share of moral dilemmas. “I’ve been in the situation where I had to say something my boss told me to do was wrong,” he said. “Another time, I didn’t have the power to change a decision. Never sacrifice your values for a company. They will not respect or remember it.”

During his book tour, Bonjean has been assessing the audience for his work. Only 10 percent have read other books about spiritual journeys, such as The Celestine Prophecy. Forty percent are interested in changing the world, but don’t know where to start. The other half buy the book because it’s an adventure set in South America. For Bonjean, it’s all about children. His son gave impetus for the book by asking, “Why do people have to pay for food?”

“I have days when I just want to buy a piece of land and forget about the rest of the world,” he said. “Then I look at my kids. If we don’t do something about unethical practices, it will be worse for them.”

‘Be willing to pay more’

In The Eyes Of Anahita is both a spiritual and a practical book.

“We have to take responsibility,” Bonjean said. “It’s us, not the government or the corporations. We have to ask ourselves, ‘What do I have to change? Are people living in poverty because of the way I live? Because of what I buy?’ Too many of us are not conscious consumers. We have to be willing to pay more for something that is locally produced rather than made in a sweatshop.”

He attacks the idea, championed by Walker and others, that sweatshop jobs are better than no jobs. “Nobody needs a job that pays one half a living wage for 17 hour days seven days a week,” Bonjean said. “Eventually, those sweatshops will just move on to someplace else where the labor is even cheaper.”

His argument is based on a moral premise most people wouldn’t argue with: Those who broke things must take responsibility for fixing them.

“Everyone should make it their business to learn how people work and live in developing countries,” Bonjean said. “Why should the rules be different in the U.S. than they are in Taiwan or China? Fair labor groups have to take the lead. Free trade is a myth. We have to change the rules so that they work for everybody.”

Consumer campaigns have forced corporations to change. “Corporations are owned by stockholders and stockholders can change them,” Bonjean said. “Socially and environmentally responsible industries are among the fastest growing in the world. One out of every eight investment dollars now goes to socially responsible firms and they are now outperforming traditional funds.”

He cites The Gap for their attempts to embrace totally transparent labor reporting. So far the clothing store has terminated contracts with 160 suppliers that didn’t meet labor guidelines.

Outsourced spiral

“Consumers want ethically produced goods,” Bonjean said. “Regular audits of the production process should be required. When jobs get outsourced, it reduces the average income and the buying power of consumers. That power is ultimately what keeps the economy going. If you keep making products cheaper, with worse labor conditions and lower environmental standards, it results in a downward spiral. The system is not sustainable the way it is.”

Bonjean feels that consumers have to educate themselves in other areas besides price.

“Young people are becoming more and more aware that they are going to have to clean up the messes we leave them,” he said. “We have to fix the holes in the bucket rather than just pouring more water in. Corporations should exist to serve the government and the people, not the other way around. Part of the problem is that global corporations have no accountability to any one place. The comfort zone in the U. S. is too good. ”

He does see people taking action on an individual basis at the local level and sees a link between values and happiness.

“Being of value to someone else or to the community – that’s true happiness,” Bonjean said.

Christopher Key is a journalist in Bellingham, Washington with a focus on business. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: