"I went to jail for income tax evasion - I told the judge, I said, 'Your honour, I forgot.' He said 'You'll remember next year, n*gger.' They're giving n*ggers time like it's lunch down there. You go looking for justice and that's what you find: Just us."

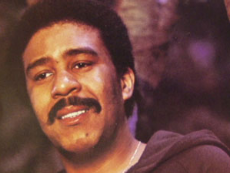

Only a few days before news of legendary artist, comedian, actor, raconteur, dramatist, performance artist - Richard Pryor's death brought me to tears in front of the television, I had been discussing the man himself with Morgan Brayton, the producer-performer behind Pink Vixen Comedy Arts, a progressive Vancouver-based initiative "committed to presenting comedy events that are artistically diverse, socially provocative and massively entertaining." Over a cup of coffee, I had explained that when it came to the pantheon of greats who had unearthed the provocative, counter-hegemonic potential of stand-up despite its having been buried under the weight of a million 'take-my-wife-please' jokes, I preferred Pryor to Lenny Bruce.

Bruce is rightly hailed for his important role in transforming the genre, tilting at the windmills of American Puritanism and rendering the form nearly unintelligible to the schticky lounge acts whose exclusive purview it had been (with the huge exception of the Chitlin Circuit whose bawdy, confrontational hallmarks had been ignored by non-black communities in the context of Jim Crow culture). Bruce's exploits and importance have been captured in countless, usually hagiographic texts such as Frank Kofsky's Lenny Bruce: The Comedian as Social Critic and Secular Moralist and films such as Lenny, starring Dustin Hoffman. But as my uncle (a hilarious man in his own right) once remarked to me with regards to Bruce: "It's too bad he wasn't funny." Pryor's work was marked by all of the accomplished, revolutionary political and artistic implications of Bruce's; but unlike most of Bruce's stuff, I told Morgan, Pryor's always makes me laugh.

The dirty truth

Many of the obituaries that have cropped up on TV and online have stressed the baseness of Pryor's material - the Toronto Star called him "profane and profound," an apt assessment of the artist's mixed foci, as evidenced in a sampling of track titles from the 1977 album Who Me? I'm Not Him: "Slippin' in Poo Poo," "Passin' Gas" and "Git a Little" on the one hand, "I'm a Negro," "Blue Eyed Devil," "Religion," and "War" on the other.

But whereas white artists with twin high and low obsessions - Philip Roth, say, or Woody Allen - have generally had little trouble (rightly) insinuating themselves into the American canon, the stunning extents of Pryor's incredible gifts have gone largely ignored, and the legacy being discussed is unfairly circumscribed. For instance, the stellar performances of Pryor the actor - in films such as The Mack, Blue Collar and Which Way Is Up? - remain some of the most meaningful meditations on race and class ever produced by the American cinema. Like each of the other creative forces enumerated above (Lenny Bruce, Philip Roth, Woody Allen), Pryor's work here was handicapped by misogyny.

The excellence of his sublime collaboration with Maya Angelou, though - in telling the story of a drunk who begins as a comic figure and ends as a tragic one - indicates the kind of unmatched brilliance Pryor had had the potential to meet were he not so encumbered by sexism.

Surreal smile

Despite this shortcoming, Pryor was truly one of the great artists of 20th century world history. A reading of his legendary hosting of Saturday Night Live, for instance - which included two transcendent monologues of unmatched pathos, comic brilliance and hypnotic storytelling - serves now to not only outline the contours of a master's creative energy, but to indicate the immensity of the potential blown by the shallowness of the comedy-variety television broadcast to achieve real social insight and break aesthetic ground.

Furthermore, at the height of his powers, Pryor was one of the world's great surrealists, unleashing the hidden narrative depths of stand-up comedy. Take the following passage from Who Me? I'm Not Him, for example, delivered in the halting, sermonizing cadence of the preacher:

God is a wonderful person. I first met God - it was about 1929. In Baltimore. Was a little hotel, I was coming down the steps. The elevator was broke at the time. I was on the 27th floor. Never will forget it. And I was walking in the hallway and I seen this man, with blue eyes. Eyes aflame. And I said 'Are you God, you blue-eyed devil?' And he said to me 'No, I'm not God, I'm the elevator operator.' So I kept on walkin'.

When I got on the streets, the sun was sittin' by the curb, cryin'. And I walked over to the sun, and I said 'Sun, why you cryin'?'. And the sun looked up, and the day got bright. And I knew I'd seen God. And God said to me 'Psst.' I walked over and I said 'What can I do for you, God?' And God said 'Do you have a quarter? It costs a quarter to get into heaven. I left my money in my other clothes, and I don't have any with me.'

And I gave God a quarter and he touched me with His power. God said to me, He said: 'I have touched the rock that turned to stone, and made the rock turn to stone that turneth.' And that moved me. I kept on walkin'. I thought it was crazy. But He touched me, and I have the power. So if you want to be healed, step right up and I'll heal you.

Pryor's frequent targets - religion, militarism, the police, racism, class - drew on precedents set by socially-engaged black comics such as Dick Gregory, but he pulled them through the filters of the absurd, as well as the disarmingly sexual and scatological.

Creative giant

Like Stevie Wonder, Pryor was a successful artist who - because of his blackness, popularity and accessibility - is nonetheless under-celebrated in relation to the virtuosic, medium-changing brilliance that he brought to bear. By the same standards used to fête Mozart, for instance - a prodigious child genius blossoms into one of the great musical talents of his, and any, epoch - Little Stevie Wonder (who only later in his career burnt out, descending to the kind of mediocrity that Mozart may have avoided only by dying so young) ought to be studied as a master.

Similarly, Pryor will largely be remembered mostly for his raunchy stand-up, as well as for having inspired the aesthetic guidelines for a generation of black comedians like Eddie Murphy and Chris Rock. He should instead be celebrated as one of the creative giants of his time, whose surreal flights and vulgarity skewered the growing absurdity and barbarism of the world in which he lived. It would be a shame to fail to recognize a virtuoso just because he's slippin' in poo poo; after all, he didn't put it there.

Charles Demers is an editor of Seven Oaks Magazine, where this article first appeared. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: