Every snowboarder knows that feeling.

The sudden weightlessness of coasting into fresh powder. Feeling untethered as your board drifts effortlessly beneath you. In his book The Darkest White, author Eric Blehm describes it as “a threshold where turning was almost intuitive.” You are lifted up, weightless. Flying.

The first time it happened to Craig Kelly was early 1981. Snowboarding was still a relatively unknown pursuit (“radical,” as Blehm puts it, considered by many “a fad”) and snowboarders were persona non grata at ski resorts. Kelly and his companions arrived at Mount Baker before dawn to poach runs before the lifts opened. Beneath them lay a snowy, blank canvas “that was so silky smooth it looked like white velvet.”

“With the wind in his face, the rhythm and ride felt euphoric all the way until gravity ran out,” Blehm writes. “It was like nothing he’d ever experienced.”

Kelly didn’t just catch the bug. He caught that first wave of snowboarding, becoming an ambassador for the sport, breaking boundaries and claiming many historic firsts. Blehm’s book viscerally describes how those initial blissful powder turns would determine the arc of his life, taking him all over the world — Africa, Iran, Turkey and Greenland — and, perhaps most significantly, to Canada, where he met his wife, Savina, and decided to settle down.

Kelly was training to become an Association of Canadian Mountain Guides-certified ski guide — and would have been the first to take the gruelling exam on a split board — when his life was cut short by an avalanche that shook the mountain community in 2003. Two decades later, questions remain about why two professional guides, Selkirk Mountain Experience owner Ruedi Beglinger and assistant guide Ken Wylie, led their groups into La Traviata, a steep couloir, during avalanche conditions rated "considerable" in the alpine.

In The Darkest White, Blehm guides readers through Kelly’s life and into the daunting beauty of B.C.’s Selkirk Mountains — and the human dimensions that can make or break a day in avalanche terrain. In painstaking detail, he unpacks what happened in the hours leading up to the deadly slide and how it claimed the lives of seven people, including a snowboarding legend.

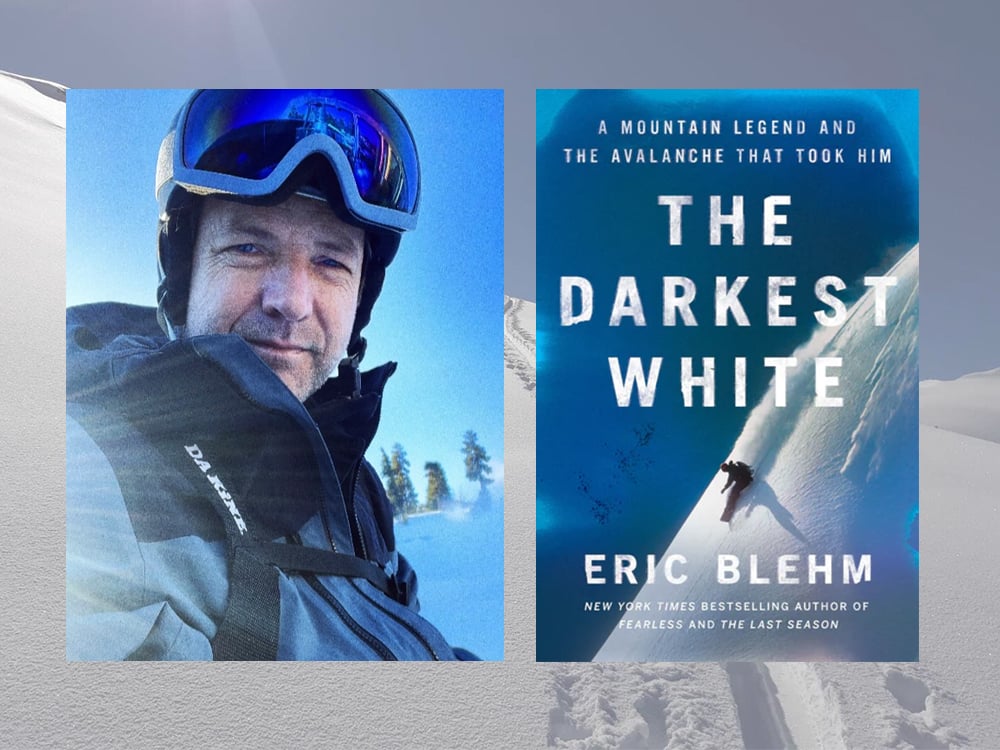

For Blehm, an award-winning war journalist, The Darkest White marks a return to his roots in outdoor adventure writing. “Craig was not just some celebrity subject,” the author writes. “I’d broken trail with him in the Kootenays, shared waves and tequila shots with him in Baja, ridden blower powder with him in Iran. He was my friend.”

Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: The La Traviata avalanche occurred more than 20 years ago. Why did now feel like the right time to write Craig’s story?

Eric Blehm: Craig was kind of like the Michael Jordan of snowboarding during my era. I was editor at TransWorld. I wrote his tribute stories in Couloir magazine and in TransWorld SNOWboarding magazine. I wrote an obituary, a short one, for Ski Show Daily and Outside magazine. Plus, Craig was a friend.

I had always had a “Craig Kelly is my co-pilot” sticker on the nose of my board. Fifteen years after he passed away, I was in a lift line in Utah and this other snowboarder, who was probably 20-something, looked down at my board and said, “Who’s Craig Kelly?” He had no idea. That was the moment. I was like, “Oh, my gosh, how is that possible? How could there be a snowboarder that doesn’t know who Craig Kelly was?”

I drove home after that trip and I went to my storage unit. There was a box with “Craig” written in Magic Marker. I opened it up and it had all the articles I’d written, trips that I had been on with him and also all the magazines that I’d collected when I wrote those original stories. As I got deeper into the box, I found the coroner’s report. I had a lot of questions. I still couldn’t quite understand how that many people could get caught in a slide with two highly trained guides. All of these questions resurfaced.

Do you think this is the most detailed accounting of what happened the day Craig died?

I know it’s the most detailed accounting. Ken’s book is his side. The stories that were written by Outside magazine and others, they didn’t have the time to go deep into speaking to everybody. Nobody ever asked questions of the survivors, like, “What do you want to know?” At the end of the day, I felt I had an obligation to the survivors to try and answer those questions.

You managed to get an interview with lead guide Ruedi Beglinger, who has been hesitant to talk to media. How did your interview with him change your perspective and influence the book?

I was on a pilgrimage to pay homage to where Craig made his final turns. To write the story, I wanted to at least understand how the [backcountry ski] operation worked, what the terrain was like. That helped me understand the feedback I got from the survivors. I also spoke with guides who had guided in that same terrain.

There’s a big thing that Ruedi says in my interview that had never been told. I really would rather not spoil it in this article, but I will say that there were things that he said that were immediately shocking, but also begged for me to double-check to make sure: Is that possible? Why would you say these things? Why would these things come out now versus way back then?

Honestly, I think what gave him, and probably Ken, trust was that I said, “Hey, I’m going to write this from both perspectives. The story that’s out there now does not add up to me. I know there’s more to it. If you can tell me anything that will allow me to understand that more fully, please do it. Because I’m going to find out. I’m going to talk to everybody.”

Were there things that changed my opinion of things? Totally. One hundred per cent. Because I went into it with, I think, the party line for a lot of people and I left with a clearer understanding, without placing blame, but a full understanding of how things went down that day. What I had learned over the years, from articles and internet chat rooms and everything, was definitely changed once I really dove into it.

It’s a testament, too, to the passage of time, that maybe people are more willing to speak. It’s less immediate, perhaps less painful.

I think that they were more willing to share. Some of the survivors have their own guilt — for certain things they did during the rescue operation or leading up to it or what happened the day before — that they always kept inside, because they didn’t want to add to the trauma. Those were tough things that people brought up that I was able to piece together. I think people realized what a big event it was and how people could learn from it today.

You unpack all those details, but it kind of becomes distilled down to a conversation between the two guides that may or may not have happened. Do you think that becomes the point that everything turns on?

Yes and no. I was careful to convey there were conflicting memories regarding that, but certain things would have still happened had that conversation not occurred. Even without that conversation, Ruedi was a fully certified ski and alpine guide. Ken was a fully certified assistant ski guide and fully certified alpine guide.

At the end of the day, there was definitely a communication issue. There was definitely a group management issue. Decisions that were made by both the lead guide and assistant guide. I took great pains to spell that out in the chronology of the book. I didn’t just rely on memories from 20 years ago; I had access to journals, letters, recordings, interviews from many of the survivors that were taken shortly after the avalanche that were never shared publicly before.

Communication is such an important part of travelling in avalanche terrain. What are some takeaways from the situation that you would like readers to understand?

First of all, I was very raw in the account. I wanted to be as raw as possible and still be respectful to the victims and the families of those who lost their lives. But I thought it was important to really give the reader an idea of what it means to be a survivor in a mass burial situation. One thing I learned was exactly that — how chaotic it can be and how so many people can be buried.

I think that probably the biggest thing that I learned was, you often hear about that little voice, the Spidey senses that come up. Multiple people conveyed their sense of “something’s not right.” My biggest thing is, don’t ignore that little voice and don’t be afraid to act on it.

Speaking in-depth with so many of the survivors and getting all the different perspectives, some people didn’t feel anything. There were other people who definitely had these thoughts, and senses, and they didn’t speak up. That has haunted them. I think that’s something that we can all learn from.

You present a narrative that’s different from the dominant one that’s been out there for 20 years. What have you heard from the mountain community?

Thus far, the feedback has been overwhelmingly positive, like, “Hey, I can see a fuller picture and can understand how this either did happen or could have happened, where in the past I couldn’t grasp it.” It’s one of the toughest accidents they still talk about in the backcountry and guiding community, and people have appreciated the unbiased reporting, which was my goal from the beginning.

I felt it was important to tell Craig’s whole story. I wanted people to know who he was and all those little elements of what he was learning along the way, and the current best practices that were going on in that community and avalanche forecasting at that time. I thought it was important to understand what Craig had gone through and then to be put in that situation.

He really did break barriers his entire life, right up until it was cut short, just before his exam.

He was the first true professional snowboarder. He brought professionalism to the sport. Then he led the charge from both getting on the mountain but also getting to the point where people were competing — that’s how they made a career, by winning and competing — to just freeriding. He was the first to make a living and get paid to freeride. He was continually pushing the envelope. Becoming a guide was just the next step.

You start the book talking about the “Craig Kelly is my co-pilot” sticker, which made me think you felt his presence as you wrote it. As I got into the second half of the book, and the avalanche, there’s a long time where he’s silent. Did you still feel him, even as the book focused on what was happening on the surface after that avalanche?

Totally. When I went to Selkirk Mountain Experience, I sat there and had my little cry, looking out and seeing La Traviata and imagining the run where he made his final turns. I could see that rise where it rolled over to where he took his last run. I knew where they dropped in and I stood there in that spot.

He was such an influencer to just always set yourself on a journey. I felt that that was what I was doing with this. I was going to follow this journey to the end. He was an engineer and I think he would have looked back and really taken it apart, had he not been taken. I feel like by reverse engineering the avalanche as I did, it honoured him.

At the end of the day, it’s a tragedy, but it’s a celebration of who Craig was. Hey, we’re all still riding, everybody that was riding with him, and we’ll never forget him. Introducing that person to the rest of the world and understanding how, at the end, the mountains got the upper hand — it’s tragic but, in a way, it’s beautiful.

I hope that there’s healing in this book, too, for those involved. Even though it was tough for some people to read, I hope that it also leads to some fuller healing. ![]()

Read more: Books, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: