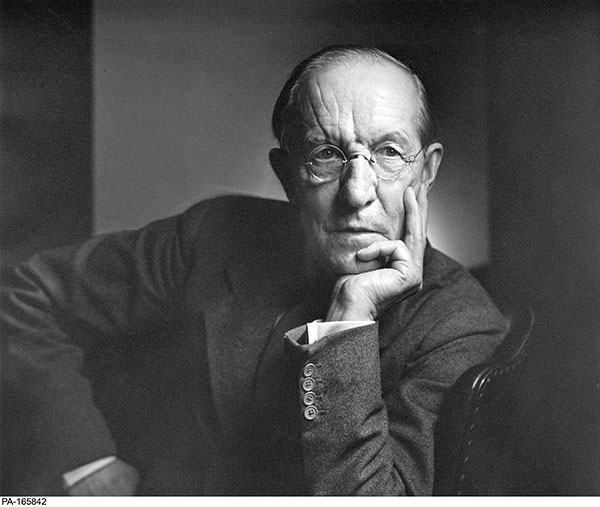

- Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott

- Douglas & McIntyre (2013)

[Editor’s note: Author Mark Abley has long been haunted by the contradictory figure of Duncan Campbell Scott, known both as the architect of Canada's most destructive Aboriginal policies and as one of the nation's major poets. In a new biography, Abley holds the longtime deputy minister of Indian Affairs to account for Canada's deplorable abuses of indigenous children, while also acknowledging the chilling attitudes that initiated the residential school program he supervised. With permission from Douglas & McIntyre, we reprint an excerpt of this frank dramatization of early 20th century colonialism.]

The traditional ways were dying: Duncan Campbell Scott believed this.

Nearly everyone believed it. The past was nomadic; the future was agricultural and industrial; he trusted it would also be imperial. The poet in him had started off as something of a cultural nationalist, keen to evoke Canadian landscapes, proud to write on Canadian themes. Yet the poet in Scott was at the mercy of his political convictions, his public faith. As an old man in 1939, he fulfilled a commission to celebrate a royal tour by delivering a servile ode in which he promised the people of this country would "do our part in high and pure endeavour / To build a peaceful Empire round the throne." The CBC broadcast the poem from its Halifax studios as the king and queen were sailing out of Halifax harbour back to an England on the brink of war. Three months before Scott died, he semi-facetiously wrote to a friend, "Why don't you order a poem on some special subject, say the marriage of Princess Elizabeth, if the CBC would pay me for it!" Against what he had called, in his ode, the "ageless, deep devotion" of Canadians to the Crown, he found it only natural to believe that Aboriginal cultures, languages and ways of life were doomed.

The surprise, or paradox, or twist of the knife is that while doing his utmost to enforce government control over indigenous people, Scott made them the subject of his most vibrant writing. Of the 11 pages Margaret Atwood found for him in the New Oxford Book of Canadian Verse, eight are devoted to poems about Indians. These items form a small minority of his total output; they also show his talents at their best. When John Masefield spoke at a memorial service held for Scott in St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London, the British poet laureate declared that Scott had been deeply impressed by many of the Indians he had met: "Admiration is a great help to understanding. In his poems and stories about them we are brought, perhaps for the very first time, to a living knowledge of what they are."

A colder view is possible. Perhaps Scott was simply using Indians for his own literary gain. In her book The Laughing One: A Journey to Emily Carr, Susan Crean condemned him as a "thin-blooded bureaucrat" who "rather perversely...wrote lyric poetry that idolized the very vanishing race whose affairs he was governing." His job gave him access to rare material, thanks to which he could make Aboriginal stories and customs appear picturesque. Yet this is not the whole story. In the early 20th century how many other writers, anywhere in the English-speaking world, would have written an ode in praise of indigenous names?

They flow like water, or like wind they flow,

Waymoucheeching, loon-haunted Manowan,

Far Mistassini by her frozen wells,

Gold-hued Wayagamac brimming her wooded dells:

Lone Kamouraska, Metapedia,

And Metlakahtla ring a round of bells.

The bells of Metlakahtla, though, were tolling an Anglican tune: this isolated Tsimshian settlement on the Pacific coast lay under the rigid control of its founder, an evangelical missionary named William Duncan who called traditional First Nations beliefs "demoniacal."

The general assumption was that the people from whose mouths such evocative names had sprung did not have long to live. "Indian Place-Names" begins in a very different spirit from the lines quoted above: "The race has waned and left but tales of ghosts..." The names, and perhaps the tales, are all that will survive. One of Scott's most accomplished sonnets, "The Onondaga Madonna," describes "This woman of a weird and waning race"; her infant child, presumably the son of a white man, is "The latest promise of her nation's doom." He wrote the poem in 1898, a year in which his department's report from the Six Nations reserve in southern Ontario, where Canada's Onondaga lived, noted that "The general health has been unusually good during the year" and "The Indians are constantly improving their homes by better ventilation." Scott the civil servant had to worry about ventilation and epidemics; Scott the poet preferred to contemplate doom.

"The Onondaga Madonna" tackles assimilation as a subject. It is tougher and more complex than the bulk of his work, which features regular appearances by mists, flowers, exclamation marks, and beauty with a capital B. The sonnet's bleakness recurs in other poems that touch on what Scott saw as the degraded condition and miserable fate of Aboriginal people. In his late poem "A Scene at Lake Manitou," for instance, an Ojibwa woman sits below some cedars and watches her adolescent son die. Against the illness that had also killed his father, the white men's medicine and religion are of no help. Desperate, the woman reverts to her old beliefs and tries to win the help of the lake's spirit by throwing her most treasured possessions into the water: a gramophone, a little sewing machine, her blankets.... The boy dies anyway. Bereaved and alone, yet still defiant, the woman stares at a line of distant, burned-out trees. The image comes to symbolize her people's destiny:

Standing ruins of blackened spires

Charred by the fury of fires

That had passed that way,

That were smouldering and dying out in the West

At the end of the day.

The image recalls a sentence in a biography Scott had written many years earlier of John Graves Simcoe, the first governor of Upper Canada: "The Indian nature now seems like a fire that is waning, that is smouldering and dying away in ashes." More distantly, it echoes some heartbroken lines that commemorate his daughter's death:

The dew falls and the stars fall,

The sun falls in the west,

But never more

Through the closed door,

Shall the one that I loved best

Return to me...

Elizabeth had brought "the beauty of sunrise" into the poet's life. Now the sun had gone. Writing to his friend Pelham Edgar a few weeks after her death, Scott said: "In no merely rhetorical way I say it seems impossible for us to go on." But he went on. Indeed, he lived another 40 years in the rambling house on Lisgar Street, where the music room would always contain, along with the grand piano and the painted landscapes, a few of his daughter's favourite toys.

The Deputy Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs would not have put it quite this way in his terse memos to the minister, but his imaginative writings suggest what he believed his day job entailed: managing the final years of a doomed people. They were smouldering. They were dying out. They were falling in the west.

A national crime

Today some people continue to look on indigenous cultures as an obstacle to progress. Interviewed on CBC Radio's The Sunday Edition, Frances Widdowson, co-author of the 2008 book Disrobing the Aboriginal Industry, informed Michael Enright that even if the now-geriatric Indian Act were scrapped or transformed, a crucial difficulty would remain: "The core problem is that you have a people that still retains a lot of features from the hunting and gathering period."

In that book, Widdowson and Albert Howard claim that Aboriginal people suffer from "undisciplined work habits, tribal forms of political identification, animistic beliefs, and difficulties in developing abstract reasoning." By hanging on to tradition, they have "not developed the skills, knowledge, or values to survive in the modern world." Their languages are utterly inadequate for modern society, and any efforts to maintain these languages do "a disservice to native people." Widdowson and Howard are dismissive of attempts to integrate traditional beliefs into the school curriculum; in their minds, such work amounts to "honouring the ignorance of our ancestors."

This last phrase -- one of the chapter titles -- is particularly offensive to many Aboriginal people. (It's also a sarcastic echo of Heeding the Voices of Our Ancestors, a book by the indigenous scholar Gerald Taiaiake Alfred.) Widdowson and Howard contend that Aboriginal people today are preyed upon by lawyers, professors and consultants who gain financial benefit from their plight; this is the "aboriginal industry" they set out to disrobe. Yet as far as the authors are concerned, much of the lamentable state of affairs seems due to the inability of the Indian to thoroughly comprehend and adequately put into effect the primary laws of civilization.

The book struck a chord. Despite the shoddiness of many of its arguments -- what the authors say about languages, for example, is absurd -- the book was widely praised in the national media (a Globe and Mail columnist called it "impressive," a National Post reviewer "valuable" and "powerful"). Such commentators were happy to overlook the hard-line Marxism that underlies Widdowson's and Howard's analysis, a Marxism that allows the authors to praise the residential schools. "Leaving aside the tragedy of incidental sexual abuse," they write, "what would have been the result if aboriginal people were not taught to read and write, to adopt a wider human consciousness, or to develop some degree of contemporary human knowledge and disciplines? Hunting and gathering economies are unviable in an era of industrialization, and so were it not for the educational and socialization efforts provided by the residential schools, aboriginal peoples would be even more marginalized and dysfunctional than they are today."

One of the many distasteful things about this passage is that its abstract rhetoric bears no relationship to the lived experience of human beings. As the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples stated in its final report, "Children were frequently beaten severely with whips, rods and fists, chained and shackled, bound hand and foot, and locked in closets, basements and bathrooms." What boys and girls endured in the residential schools was not just a socialization effort. It was indoctrination, enforced by what plenty of observers at the time recognized as physical and mental abuse. To take but one example, Bill Graham, an inspector of residential schools in southern Saskatchewan, informed headquarters in 1907 about abuses at Crowstand, a Presbyterian school near the town of Kamsack. Graham noted that when retrieving some runaway boys, the principal of Crowstand had tied the children to ropes and forced them to run eight miles back to school behind a buggy. The department urged the Presbyterian church to dismiss the principal, but the church declined; there was no room in the wagon, it said, and the horses were not trotting fast.

In 1921, when Scott was in control of Indian Affairs, he reacted with anger after a nurse at Crowfoot School in Alberta sent a disturbing report to his department. A complaint about poor food had led her to enter the school's dining room unexpectedly. There she found four boys and five girls chained to the benches. One of the girls had been badly scarred by the strap. Scott wrote to the school's principal, an Oblate priest: "Treatment that might be considered pitiless or jail-like in character will not be permitted. The Indian children are wards of this Department and we exercise our right to ensure proper treatment whether they are resident in our schools or not."

But the department almost never did exercise its right. John S. Milloy's superb book "A National Crime": The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986 gives many examples of other reports that landed on the desks of Indian Affairs but were never acted upon. Scott could compose a chilly letter to Father Riou at Crowfoot School, but he had no power to fire an offending principal; that would be up to the church, and the church, whether Protestant or Catholic, generally refused to act. Time and again, teachers, nurses or Indian agents would inform the department of hunger, violence, overcrowding, sodomy, disease, brutality, escapes, drastic incompetence, deaths; and the department would make a recommendation, offer a suggestion or file the matter away for possible action at some point in the future. It often declined to do even that much, choosing to reply that the complaints were excessive, the charges unproven or the complainants unreliable.

The government could, and did, point an occasional finger at the churches, whose ability to manage the schools was so patently dismal. But the churches could, and did, point an occasional finger back at the government, which never gave them enough money to operate the schools in a humane or efficient way. For many years the per capita amount that Ottawa granted the churches for Indian education was about half what it provided for orphanages and homes for white children. The finger-pointing was mild and genteel. The treatment of Aboriginal children was anything but.

Scott did his best to hide this news from the public. Troubled by a complaint about the physical abuse of children in the Mohawk Institute near Brantford in 1913, he composed a memo to his minister, W.J. Roche, admitting and deploring the use of corporal punishment: "The rules governing the disciplinary action in the case of misdemeanours by pupils, are I think antiquated...I do not believe in striking Indian children from any consideration whatever." But when he wrote to the lawyers acting on behalf of the complainants, he sounded a different note: "No necessity exists for the investigation which is asked for by the Indians mentioned. That it is a popular Institute is shown by the fact that the waiting list contains the names of 80 children whose parents are anxious for them to attend." In fact the Mohawk Institute was known by many of its inmates as "the mush hole."

Ten years later, answering a question from a parliamentary reporter, Scott made the outlandish claim that "99 per cent of the Indian children at these schools are too fat." (The reporter knew of a letter that a boy in the Saskatchewan school of Onion Lake had sent to his parents; the boy had complained about cruel treatment and lack of food, mentioning that seven children had tried to run away because of extreme hunger.)

Despite the official lies, at least part of the truth was available to anyone determined to look for it. In 1907 Samuel Blake, a reform-minded lawyer for the Anglican church, had told the minister of Indian Affairs that "the appalling number of deaths among the younger children... brings the Department within unpleasant nearness to the charge of manslaughter." The minister was unperturbed. The department's annual report for that year made no mention of Blake's charge, although Frank Pedley did lament "the retarding and retrogressive influences of the home upon the pupils" and the "hostility [that] results from superstition." Families, once again, were proving to be a bad influence. Failure, once again, was the Indians' fault.

Blake did not give up. He wrote to the Attorney General's office in Edmonton, seeking details about "the Indian question" in Alberta. In March 1908 a reply came from A.Y. Blain, the inspector of legal offices for the province. Blain, who had only recently moved to Alberta from Ontario, told Blake that he had now met all the members of the legislature "and made a point to get what information I could in regard to the Indian from such of the Members as had reserves in or near their districts." He had consulted other Albertans too. The results were discouraging. "I might say," Blain wrote, "that most of those with whom I have spoken are not, I would gather, very much in sympathy with the Indian, nor with the efforts to better his condition. They look upon him as a sort of pest which should be exterminated."

From the book Conversations with a Dead Man: The Legacy of Duncan Campbell Scott, © 2013, by Mark Abley. Published in 2013 by Douglas & McIntyre. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: