It’s not a lighthouse or an old church, but the home of the Wongs’ Benevolent Association holds just as much history as these symbols of nostalgic Canadiana — all of which are competing for funding crucial to their survival.

Their building, with the memorable address of 123 E. Pender, is one of the most beautiful in Vancouver’s Chinatown. In early 1920, the Wongs began adapting an existing commercial building into their new headquarters, a classic example of East-meets-West architecture. There’s an ornamented parapet, the recessed balconies you would have found in 19th-century Guangzhou, and a colourful stained-glass window set over the entrance.

That entrance brings you to a steep flight of stairs, where generations of Wongs have gone up to find one another after arriving in Canada. Inside, they’d get their bearings and connect to basic needs like work and housing.

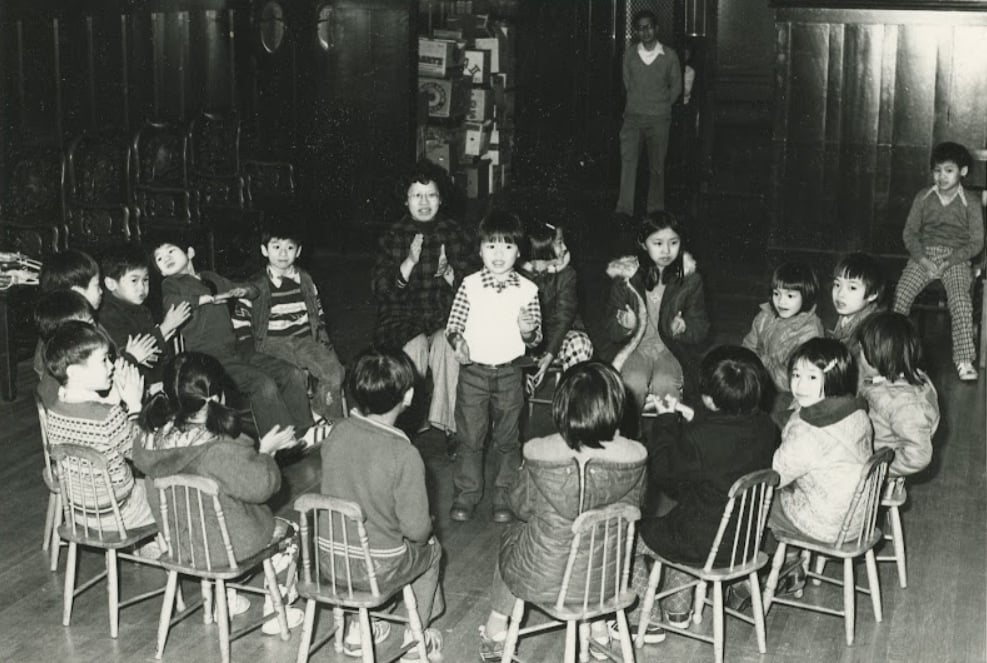

Generations of children have run up those stairs for their Chinese-language classes at the Mon Keang School on the third floor, run by the Wongs and welcome to all. The school was established in 1925, in the middle of the exclusion era when Canadian borders were closed to Chinese people. As a result, the school was a precious place where Canadian-borns came to learn how to read, write and speak Cantonese, with some worry that they might need the skills if they were expelled from the country.

To this day, immigrant seniors trudge up those stairs to hang out. The association is a comforting place for culture and connection, and the seniors faithfully made it here during the pandemic, sitting masked and physically distanced in the large rooms, to keep each other company.

But the building is getting old.

There’s water damage. There’s a spot on the covered balcony where chunks of the ceiling have begun to fall off. And when the building was crowded with Wongs during the recent Lunar New Year celebration, the taps and toilets struggled to work.

The Wongs’ Benevolent Association is one the most established of Chinatown’s family and village associations. The fact that their building requires urgent repairs doesn’t bode well for the rest who own properties in Chinatown, many of which are over a century old. What little revenue these associations collect comes from member donations and — for those who happen to have the real estate — rent from business and residential tenants.

As a result, their operational future is at the mercy of external funding like grants — awarded to independent organizations and non-profits through rigorous application and review processes.

In the Wongs’ current case, the money for the urgent repairs lies in the hands of voters in a national contest.

‘Do it ourselves and do it cheaply’

The Wongs submitted the Mon Keang School, on the third floor of their building, for the National Trust for Canada’s Next Great Save contest. It made it into a group of 12 finalists vying for one of three cash prizes totalling $65,000 to help restore historic sites.

Public voting is underway on the contest website until May 6, and voters can cast a ballot every day.

Mon Keang School is one of two finalists located in British Columbia, the other being the St. Andrews Lodge of Qualicum Beach. They are facing competition from buildings like the streamline moderne LaSalle Theatre of Kirkland Lake, Ontario, and the Our Lady of Mercy Church on a hilltop in Port au Port, Newfoundland and Labrador. One unique entry comes from Alberta, a grain elevator in Nanton.

Without access to such funding in the past, the mindset at the Wongs’ and other Chinese benevolent associations was to “do it ourselves.”

“And to do it cheaply,” said Aynsley Wong, one of the association directors. “Of course, we’re finding out now that it was cheap. They deferred some maintenance that probably should’ve been addressed much earlier because the problem compounds and becomes really costly.”

Aside from the main headquarters, the Wongs own another property on nearby Pender Street, home to their Hon Hsing Athletic Club. That property has a lightwell, and a member put up sheet metal to cover three damaged walls. The association later discovered asbestos and a buildup of rot.

The other issues with grants, especially those from governments, is distrust.

“Our elders are the elders who were around during the viaducts,” said director Jeffrey Wong, referring to the public expropriation of homes, businesses and a Chinatown society in the 1960s in the name of “slum clearance.”

“They still have a theory that the government is out to get them,” he explained, with worries that taking grant money could result in them being seized entirely.

In recent years, the Wongs have sat on committees with other associations to bring their shared concerns to city hall, which has helped create resources and offered money for repairs.

That being said, repair issues shouldn’t belie the strength of the building and the association.

Andrew Sandfort-Marchese, a volunteer helping the Wongs sort through their archives, is amazed by the efforts of members to support one another and keep things running over the years.

“To do this work, you have to have the volunteer time. You have to have some cultural or language skills. You have to be a carpenter, a contractor. You need to know asbestos remediation. You have to be able to work well with seniors, with young people; to be able to work with businesses. This is a testament to the passion of these individuals and everyone who’s doing it. It’s not easy.”

The generations come back

In some ways, the success of Wongs in the postwar years meant that they didn’t need the aid of such a society.

Aynsley’s father is Randall Wong, who became the first Chinese Canadian Crown counsel in 1967 and later a Supreme Court judge in 1990.

“He had his life outside of Chinatown,” she said. “My parents graduated from UBC in the 1960s and they had the freedom to do that for the first time, to work in other places, to live where they wanted.”

Because of this, her father and her peers are sometimes called the “lost generation” for being absent from Chinatown life. But after retirement, he came back to volunteer in the neighbourhood.

So did Aynsley.

In 2011, Mon Keang was down to three students and closed due to the lack of enrolment. But in 2016, a group of young people started up classes again in the historic space, called Saturday School.

Aynsley signed up for the classes, which took place in the very rooms her father spent time in all those years ago when he was a Mon Keang student. One of his memories: the kids spending recess playing on the roof, where they would pee off the edge.

Saturday School was known for its interactive learning, with students sent into the neighbourhood to practise their conversational skills at shops and grocers.

After that, Aynsley started helping out at the Wongs’ and became a director in 2016.

“There was some resistance to having a woman on the board,” she remembered. Looking at the walls of the association, it’s not hard to see why with the many black and white photos of male directors over the years.

Her father wasn’t the only alumnus who thought back to his Chinatown schooling later in life.

During the pandemic, the association received a cheque from Hin Lew, the first Chinese Canadian physicist, who earned his PhD at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and worked for the National Research Council during and after the Second World War. He was in his 90s and wanted to repay a Mon Keang principal who had lent him $100 for his studies.

Nowadays, a younger generation — nowhere near retirement — is taking interest in the association.

Frank Wong, the current president, is pleased to see this. He knows succession is key to the survival of associations like the Wongs’. When Jeffrey joined at age 23, for example, the next-youngest member was 70 years old.

“I’m sorry for making you do so much, ha ha!” Frank joked with Aynsley, Jeffrey and Sandfort-Marchese in the manner of an uncle on a recent Monday.

‘Not just about the heritage’

There is indeed a lot to do.

It would be great if they won the National Trust contest, though they know their seniors are not the tech-savvy type accustomed to casting votes online. “We’re asking them to tell their kids to vote every day,” said Jeffrey.

With or without the money, they’re scouting out other sources of funding ahead of the school’s centennial in 2025.

Aside from that, there are artifacts and photographs to digitize. Jeffrey and Sandfort-Marchese have passed by many a Chinatown alley to find documents in the dumpsters, dated in years of the People’s Republic of China, chucked in with chicken bones and rotting produce. It’s not uncommon for smaller associations to get rid of their records, they say, whether because of a move or because the record keeper has died. The Wongs, in comparison, have a well-kept collection, but it needs sorting through.

There are members to care for. Some 3,000 are registered with the association, though the directors are sifting through birthdays to remove the names of those who couldn’t possibly still be alive. Pre-pandemic, there were over 500 people in attendance at the annual dinner and about 50 seniors attended regular activities. Now, it’s a smaller, dedicated group who make it down to Pender Street for the company.

There are also tenants to care for, including the 112-year-old Modernize Tailors.

There are tours to arrange, to give the public a peek inside the storied building.

There’s the Saturday School, which is rebooting this summer after a pandemic pause.

“It’s not just about the heritage of our buildings, not just about the look of our buildings — it’s about what goes on inside,” said Jeffrey. “It’s not a museum. The things that we’re practising are things we’ve been practising for 100 years, but we’re also making things new.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: