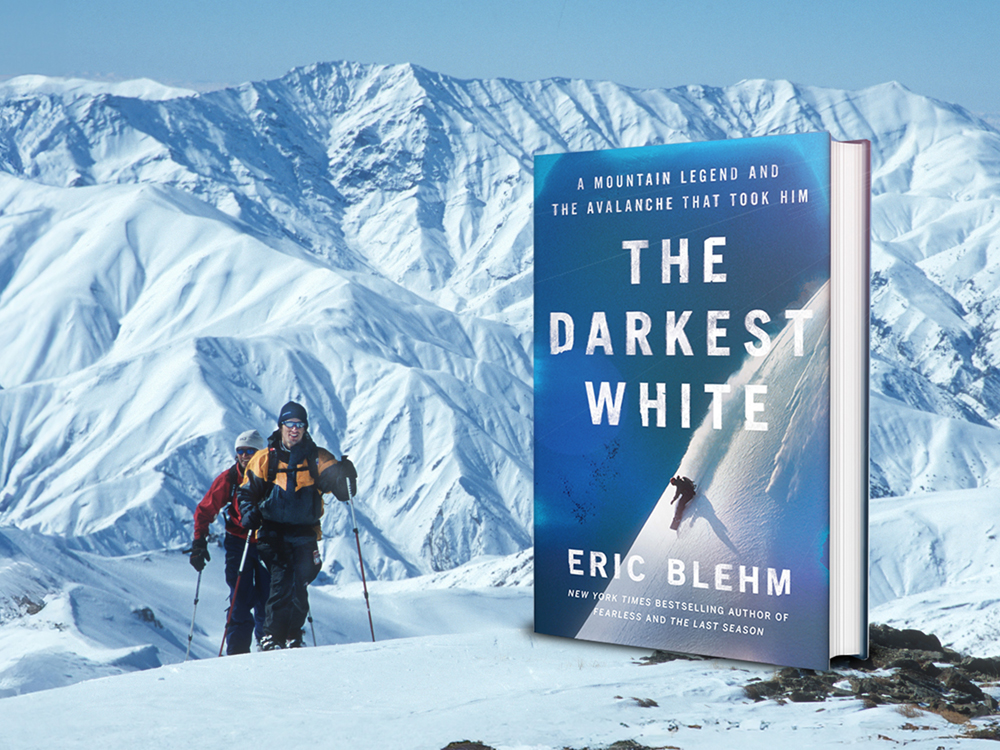

[Editor’s note: In ‘The Darkest White,’ New York Times bestselling author Eric Blehm delves deep into the life of snowboarding legend Craig Kelly, whose life was cut short by an avalanche that killed seven people in the Selkirk Mountains in early 2003. The story begins with Kelly’s upbringing in the United States and follows his tracks to Canada, where Kelly would take his final turns while training to become a certified ski guide — the first snowboarder to be accepted into the program. ‘The Darkest White’ is the first thorough accounting of that tragic day, which shook the mountain community, and the life of a snowboarding pioneer who continued to smash boundaries until the end.]

Fifty thousand spectators descended upon Aspen, Colorado, in the last week of January 2003 to watch the most “extreme” athletes battle it out in alternative sports’ biggest arena: the Winter X Games. Many in the record-breaking crowd came specifically to cheer on a red-headed snowboarding prodigy named Shaun White. Not yet an Olympian, he was well on the road to becoming one of the most famous athletes on the planet — mainly for the manner in which he briefly shot himself into orbit above it, launching off monster jumps and halfpipe walls with the precision of a gymnast and the recklessness of youth.

The Superpipe was mobbed with thousands of fans who hushed as White, only 16 years old, dropped in for his final run. Cameras from major sports networks and magazines followed his every move, and the crowd roared as he soared above the perfectly shaped halfpipe, spinning and inverting his body and board into history as the first snowboarder to win back-to-back (Slopestyle and Superpipe) X Games gold medals.

Second only to the Olympics as a televised and marketed winter sporting enterprise, the X Games snowboarding scene was electric — a hyped-up, commercialized, energy-drink-sponsored rock concert on snow; a supercharged mutation of the stark, humble and fiercely independent alpine soul that had birthed the sport decades before.

Obscured though it may have been by the glare of stadium lights and the alien neon of plastic-wrapped sugar water, it was a soul that nevertheless still lived in many of the competitors and fans present. It was the soul of the mountain town or surfer and skater kids who’d grown up with boards attached to their feet and ice crystals in their hair. It was even the soul of some of the board sponsors like Burton and Sims who now reaped the financial windfall of a world their founders had created from planks of wood.

But on this day, there was another manifestation of that soul, a silent rider in the form of a sticker displayed by many in the crowd, and worn by Shaun White himself on his chest during his winning run, a rectangular white decal that read in bold black letters: “Craig Kelly is my co-pilot.”

Most casual fans didn’t even notice the message, but those who did understood that it celebrated the life of a beloved snowboarding legend who had been killed just a week before — on Jan. 20, 2003, by an avalanche in the Selkirk Mountains of British Columbia.

Craig Kelly had been a guiding force to a generation of snowboarders who revered him, a compass pointing the way. Once a fierce competitor himself, Craig was snowboarding’s first true professional and four-time world champion. He had stood at the top of the podium more times than anybody who’d ridden a snowboard during the 1980s and into the ’90s as the sport burst to life and rapid global influence.

His own story was an epic adventure, an alpine odyssey that catapulted Craig — a latchkey kid of divorced parents from small-town Mount Vernon, Washington — around the world multiple times as he helped make snowboarding a worldwide cultural and commercial phenomenon.

Craig’s contest results and global rankings made him snowboarding’s first international superstar, but when given the choice of more fame and fortune, he followed his heart. He turned his back on business deals, high-dollar sponsorship contracts and the prize money associated with competition and returned to the powdery backcountry that had first drawn him to his calling. In the process, he inspired people from around the globe to follow him there.

I was one of them.

The early days

I first “met” Craig Kelly in the pages of International Snowboard Magazine in the mid-1980s before most of the world even knew what a snowboard was. A subscription to ISM in 1985 was like membership to a secret society filled with cool characters who were defining a culture one tweaked air at a time.

There was Terry Kidwell, Shaun “Mini Shred” Palmer, Damian Sanders, Evan Feen, Steve Matthews, Scott “Upside” Downey, Jon “Boy Air” Boyer, Chris Karol, the Achenbach and Coghlan brothers, Tom Burt, Jim Zellers, Bonnie Leary — I remember them all — Mark Heingartner, Dave Alden, Keith Kimmel, Lori Gibbs. Names most people never heard of, even then.

I ended up writing for, and ultimately became the editor of, another magazine I worshipped called TransWorld SNOWboarding. It was the best job I could imagine — getting paid to see the world and ride powder with my heroes. During these early years of the sport, one name — “Craig Kelly” — became all but synonymous with snowboarding. And then, suddenly, he disappeared from the public eye and as a perpetual presence in our pages.

There were occasional sightings, rumours that placed him in the fish markets of Ensenada, Mexico, then months later in the jungles of El Salvador, at an internet café in Puerto Montt, Chile. And then again for great stretches of time, there was nothing. Only “historical” rerun photos of him in the mags, cementing his place in the canon of snowboarding’s golden age. During his absence, his legend settled comfortably in the hearts and minds of his many fans and drifted into lore — the Obi-Wan Kenobi of snowboarding.

But Craig’s story wasn’t over; he’d just followed his bliss to an isolated corner of what he called “snowboarding dreamland” — British Columbia — and, much as he always had, was quietly working on what was next.

Trouble in paradise

You can go there, too. Just follow the Big Bend Highway out of the town of Revelstoke, British Columbia. At Carnes Creek, make a hard right and fly (yes, fly — you’re in a helicopter) up the drainage into the wild and remote northern Selkirk Mountains. The aircraft will skim treetops and frozen waterfalls until you’re so far from the nearest road that you could scream and your voice wouldn’t make it halfway to anywhere. Shortly after you ascend above treeline, you’ll blast into the white lunar expanse of the alpine. This is the T-intersection at Tumbledown Mountain. You could bank left and fly toward Seven Ravens Knoll or instead bank right, skirt the western flank of Goat Peak and descend toward a red-roofed chalet perched in absolute solitude on a subalpine knoll with sweeping views of the Selkirks in every direction, their jagged peaks intersected by deep gullies, rock-lined couloirs, cornice-rimmed bowls and miles upon miles of glaciers.

When Craig landed there on Jan. 18, 2003, a skier he had flown in with said simply, “Welcome to paradise.”

Sixteen years later, when I landed at the same spot, I wasn’t so sure.

This was, after all, the “paradise” that killed Craig Kelly, who, let’s be clear, hadn’t even seemed mortal. He was a superhero born from a blizzard on a sleeping volcano. He levitated down mountains, raced avalanches, aired cliffs and landed on the covers of magazines. “If gods walked the Earth,” says photographer Gordon Eshom, “Craig was one of them.” That’s not hyperbole.

“We all believed it,” says fellow pro rider Jason Ford, “right up to the moment we heard the impossible news of his death.”

I had been asked to write a couple of memorial tributes to Craig plus an obituary when he died, but it took me 16 years to pay my respects at the place of his passing. When I landed on that same knoll and walked into the Durrand Glacier Chalet in the spring of 2019, I knew I was looking for a kind of closure that had eluded many of the friends and family of those who died that day in 2003, as well as some who had managed to survive.

The Durrand Glacier Avalanche, as it came to be known, had been the first of a duo of avalanches in this range that left 14 people dead and was deemed the “deadliest fortnight” in North American backcountry skiing and snowboarding history. These incidents prompted hard questions about risk management, the ethics of guiding, and accountability. Canada’s National Post newspaper stated that the Durrand avalanche in particular “changed backcountry culture” forever.

My pilgrimage to the Durrand began when I asked a guide friend if he would mind introducing me to the lead guide in charge — the fiercely proud proprietor of Selkirk Mountain Experience, Ruedi Beglinger — the man who had, directly or indirectly, led seven people to their deaths. I asked him to tell Beglinger I was writing Craig’s story to honour his life and the lives of all of those who were killed that day; I wanted to tell the entire story of the avalanche, still a controversial and emotionally charged disaster nearly two decades later.

For months my friend told me that Beglinger had not replied, but the truth was he had, with a definitive “no.” He had been harshly vilified for years, and had zero interest in talking to me if my questions were about the avalanche.

If I couldn’t ask questions, I figured I could at least ride with him. So, I attempted the standard process to book a week at SME, and followed up with a letter that further explained who I was and what I hoped to do. Beglinger needed to understand that Craig was not just some celebrity subject for me. I’d broken trail with him in the Kootenays, shared waves and tequila shots with him in Baja, ridden blower powder with him in Iran. He was my friend.

Beglinger and his family also lost friends that day, so I expressed my condolences and wrote, “I have waited 16 years to visit where Craig took his last turns, and I am wondering if you’ll welcome me to at least experience the area. If you wish, I will not ask you a single question about the avalanche. Not one question.”

A week later, I received a call from Beglinger’s office manager. “We have a cancellation — you’re in.” A month later, I was one of 15 guests who were helicoptered in, five at a time, while guests from the previous week were flown out. Beglinger was right there as my group stepped off the skids, welcoming return clients with hugs, and for me — and other first-timers — he pulled off a glove and shook my hand.

The slightly built, sun-and-wind-weathered guide was now 63, but if his grip was any indication, he was as strong today as he had been when he’d first met Craig at this exact spot. “I’m Ruedi,” he said in a heavy Swiss accent. “I’m Eric,” I returned. “Ya, I know this,” he said with a glance down at my soft snowboard boots, the tell among the other guests, who wore hard-shelled ski-touring boots. “You are our only snowboarder this week.”

If I felt singled out, it was only for a moment, because for the next seven days I was just a part of the group, having paid my fee to be led through these storied mountains. Each morning, we rose before the sun, packed lunches, ate breakfast and by eight were walking, a.k.a. touring, away from the chalet in the Nordic tradition: with climbing skins affixed to our ski bases (I was using my split snowboard in ski mode) for uphill traction. We followed guides whose goal was to take us to the mountains’ secret places — to share what they knew and revealed — and in the process we learned a little something about ourselves.

After climbing through forests, traversing icefalls and crossing glaciers for hours, we would ski or ride down for miles — 6,000 vertical feet per day, the guides testing the slopes as we went, observing our skills, assessing our fitness and determining if our group was more suited to roll into a particular run or push farther up the ridge, tiptoe past some exposure and drop into a hidden, steeper aspect with mandatory air. Each weightless powder turn that followed wasn’t just a reward; it was a reminder of what Craig Kelly had considered the essence of snowboarding — the freedom of climbing and descending through nature’s forces and harnessing them just enough to collaborate with gravity.

Exhausted, we’d return to the chalet single file in the evening, have a sauna, stretch, a snow bath for the brave, followed by a beer, a book or a nap. At 6:30 p.m., we’d sit down to a meal, shoulder to shoulder with strangers who were becoming friends.

Halfway through the week and shortly after breakfast, I laced up my boots, turned on my avalanche transceiver and joined the early risers assembling outside. It was snowing lightly and grey and the steep alpine faces that rose up before us were shrouded by the flurries of a gathering storm. We focused on the seemingly impassable Goat Peak, whose ramparts and ridges separated us from our objectives that day.

Several of these guests, including a judge and a lumber baron with his family who had been returning here for decades, fielded questions from us first-timers, pointing out runs they’d done in the past while speculating which route or passageway — “Needle Icefall... maybe the Ledges” — would take us up, over or through this daunting quandary of rock, ice and snow.

As 8 a.m. drew nearer, the wind picked up, and most of this crew leaned on their ski poles, gazing at the routes with a relaxed calm, but I and a few others shuffled about and stomped our skis, anxious in the gate.

It was serious business, and there was a pervasive sense of adventure and a giddy, maybe nervous levity just before heading out. I was grateful for the camaraderie and human comfort that somehow manage to make a habitat of nature’s extremes.

It was paradise.

A minute, maybe two, before 8 a.m., Beglinger rounded the corner of the chalet. Big feathery flakes were drifting down lazily, a gift from the heavens that he marched through with his signature strong, confident gait, not toward the head of the group like he had the past few mornings, but instead, directly to me.

“Eric,” he said, pausing briefly, face to face. “Maybe later, after we ski, we talk.”

Excerpt from ‘The Darkest White: A Mountain Legend and the Avalanche That Took Him’ by Eric Blehm, copyright 2024. Published by HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved. ![]()

Read more: Books, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: