B.C.’s drug decriminalization pilot is in tatters after concerns about drug use in hospitals and restaurants led Premier David Eby to ask Health Canada to make public drug use illegal again.

The request to reimpose criminal penalties on people who use drugs in public spaces has energized political opposition to both decriminalization and safe supply from right-wing parties in Canada.

B.C.’s Opposition party, BC United, has called for the entire decriminalization pilot to end, saying the policy is “reckless.” The B.C. Conservatives have taken the same position.

But advocates are warning that restoring criminal penalties for users for possessing small amounts of drugs will mean they will turn to the toxic illicit drug supply.

And the ban on public use will lead to people using substances alone and in hidden places, raising the risk of more deaths from overdoses, they warn.

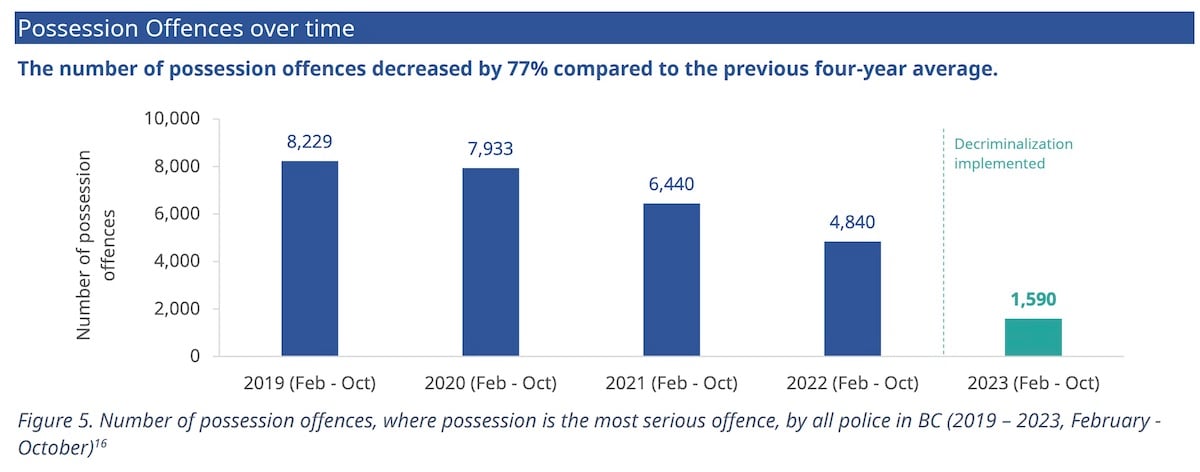

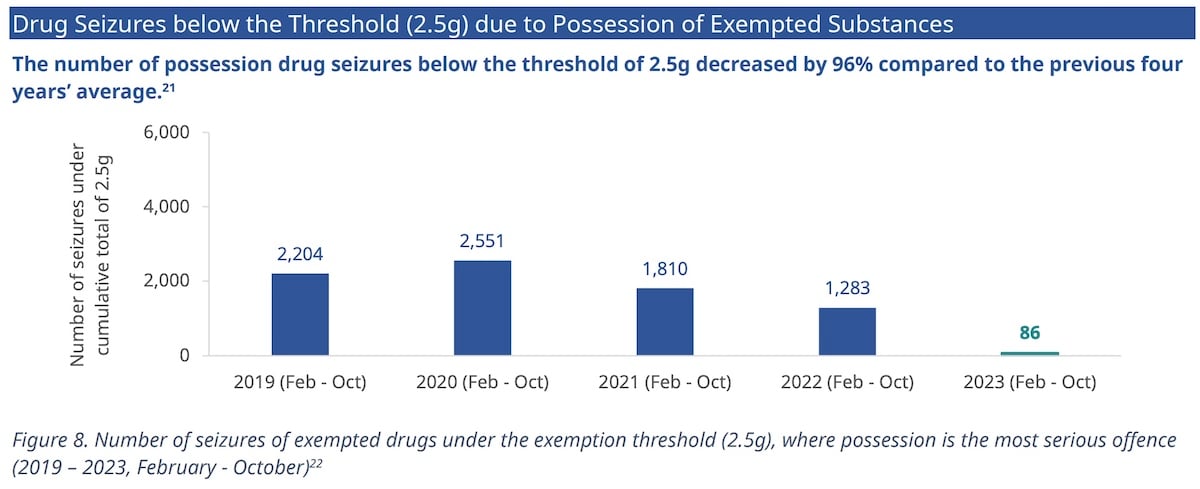

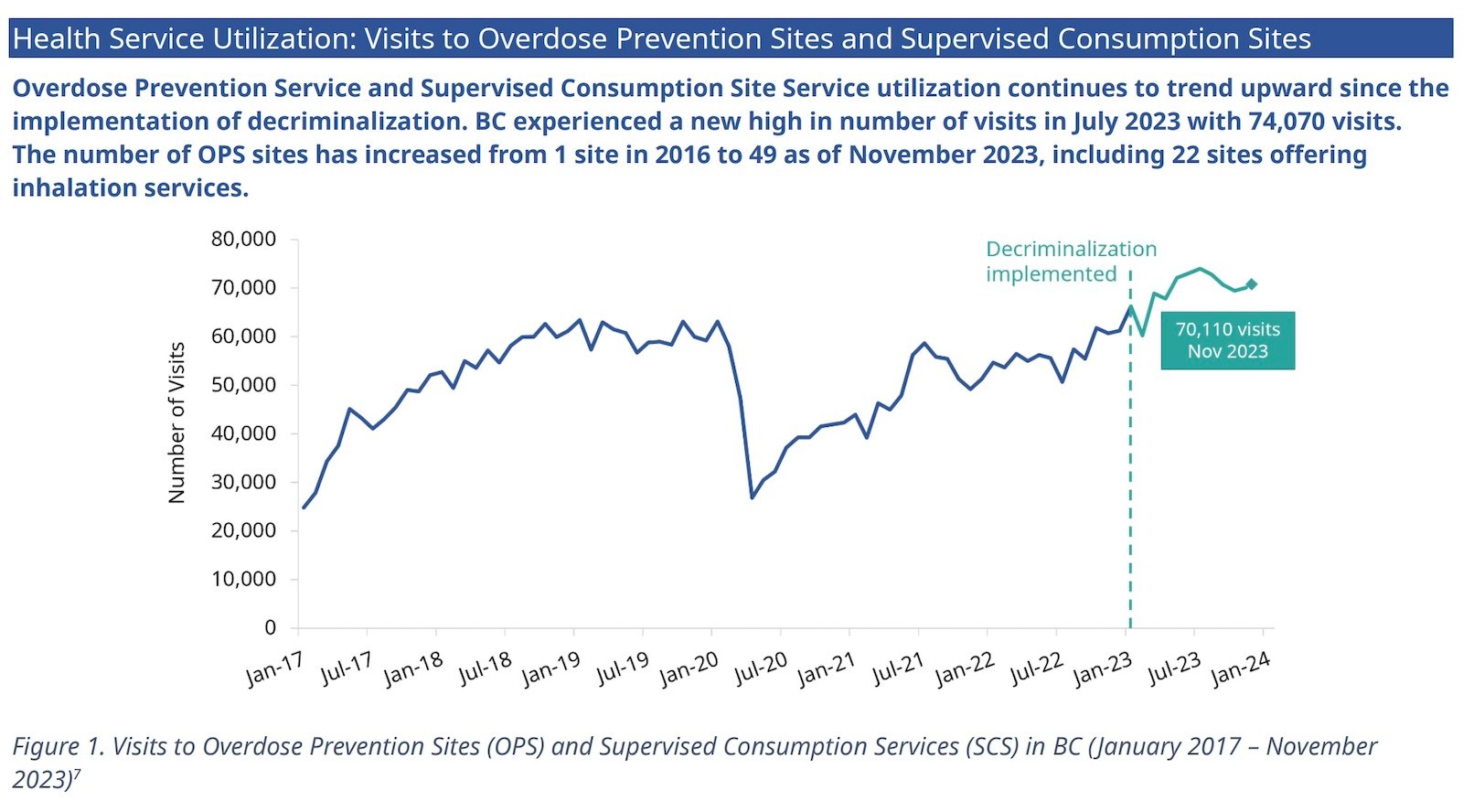

Statistics from the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions show the policy was working as intended. Drug seizures and arrests for possession of small amounts of drugs have dropped, while visits to overdose prevention sites have continued to rise.

Criminal penalties for public use will increase danger, say advocates.

“If you’re an unhoused drug user and you live in a community that doesn’t have a supervised consumption site or an overdose prevention site, which is the case in the vast majority of communities in B.C., your existence is effectively criminalized,” said Caitlin Shane, a lawyer with Pivot Legal Society.

On April 26 Eby said he would ask Health Canada to remove the exemption to Canadian drug laws to allow limited public drug use. The exemption was part of B.C.’s pilot decriminalization program.

Eby said he was concerned about reports of open drug use in hospitals and restaurants. Police needed tools “to address extraordinary circumstances where people are compromising public safety through their drug use,” he added.

Shane pointed out that under the decriminalization pilot — which legalized possession of small quantities of opioids, cocaine, meth and MDMA — drug use was never legal in hospitals, restaurants or playgrounds.

But Adriane Gear, president of the BC Nurses’ Union, said drug use inside some hospitals did become an issue after decriminalization came into effect at the end of January 2023.

Those problems included nurses and other patients being exposed to illicit drug smoke and some patients acting erratically after using substances. Some nurses were also concerned about drug dealers coming into hospital rooms to sell drugs to patients.

“Very early on, some of the health and safety concerns were certainly being noted,” Gear said. “It wasn’t everywhere, but there were pockets.”

Gear said the blame should fall on the health employers who were failing to enforce their own policies and were “gaslighting” nurses when they raised concerns about patient and workplace safety.

But she said Eby’s request to Health Canada will provide “clarity around where behaviour of consuming substances can happen.”

Decriminalization pilot had a rocky start

B.C.’s decriminalization pilot removed criminal penalties for people 18 and older, who are allowed a combined total of 2.5 grams of opioids, crack and powder cocaine, meth and MDMA for personal use. The pilot will run until Jan. 31, 2026.

But after hearing concerns from local politicians, B.C. MLAs passed an update to the decriminalization pilot project, Bill 34, last fall. The bill prohibits the possession or use of drugs within 15 metres of a playground and within six metres of the entrance to a building, the entrance of a park and bus stops, among other places.

The Harm Reduction Nurses Association challenged that law in B.C. Supreme Court, arguing it could cause “irreparable harm” to drug users. Justice Christopher Hinkson agreed and granted an injunction that prevented Bill 34 from coming into force.

But after media stories about patients smoking illicit drugs in hospitals and in a Tim Hortons in Maple Ridge, Eby said British Columbia residents “can’t afford to wait” until that court challenge is resolved many months from now.

During a press conference on April 26, Eby said Prime Minister Justin Trudeau assured him that “the federal government will provide full support to ensure the police have the tools that they need.” Eby said decriminalization will still apply inside private homes, overdose prevention sites and homeless shelters, but using drugs in any other location would be illegal.

Eby also said the court injunction that prevented Bill 34 from coming into effect was “a challenging and frustrating moment.”

Shane said the debate hasn’t been based on facts.

“It’s frustrating to see politicians talking about use in playgrounds, hospitals and restaurants as somehow being the result of either decriminalization or of HRNA legal challenge,” Shane said.

“These things aren’t related, those activities... were already illegal under decriminalization. Hospitals have their own policies surrounding possession and use in those scenarios, and they weren’t ever to be impacted by Bill 34 or the challenge.”

What problem was decriminalization supposed to fix?

Right-wing politicians across Canada have been pushing back against decriminalization, safe supply and, in some cases, overdose prevention sites, saying that treatment programs to end drug use are the only viable solution to the deadly overdose crisis.

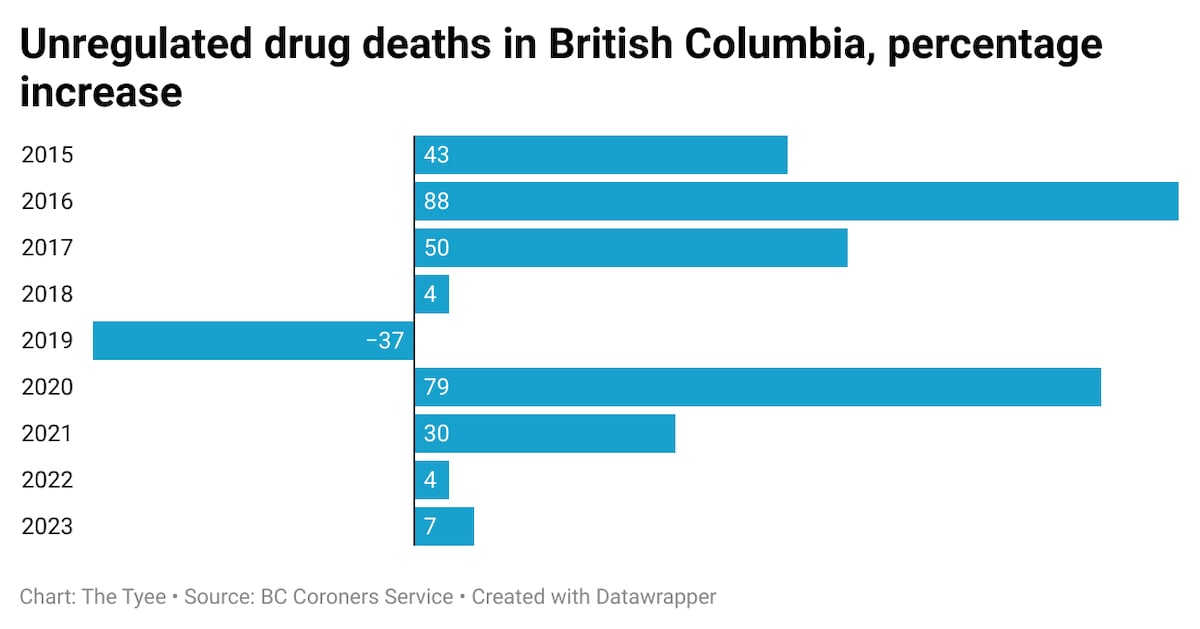

“[Trudeau’s] extreme and radical drug policy has increased overdose deaths in British Columbia by 380 per cent,” Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre claimed in the House of Commons Monday.

Poilievre then blamed B.C.’s rising overdose deaths on decriminalization.

“In the year following his decriminalization of crack, heroin and other hard drugs in hospitals, transit buses, coffee shops and parks where children play, there has been a record-smashing 2,500 deaths.”

According to the BC Coroners Service, 2,546 people died of overdoses in 2023, the highest number ever recorded and a seven per cent increase compared with 2022.

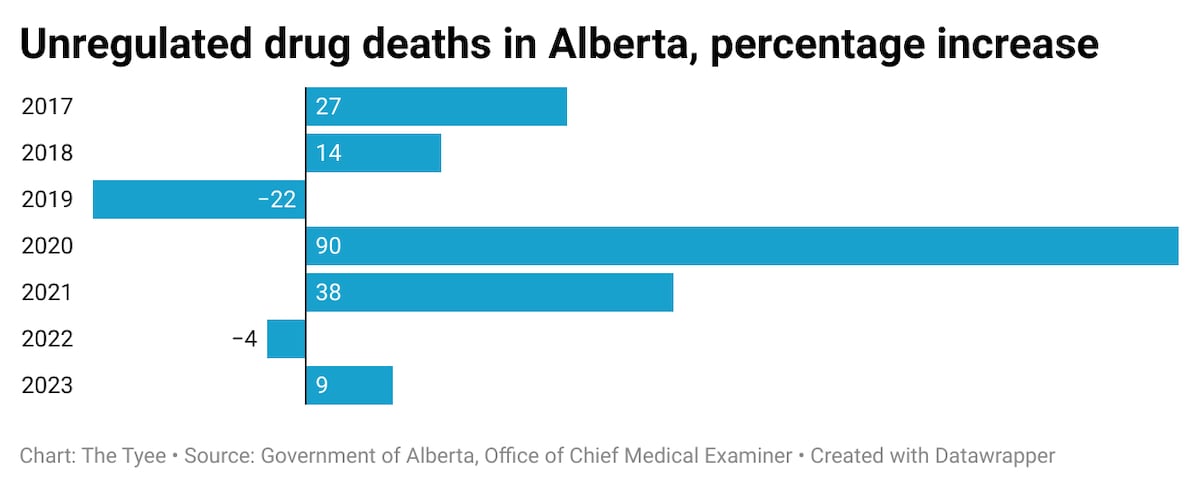

In Alberta, a province that does not have decriminalization or safe supply programs and has closed several overdose prevention sites, the death toll rose by nine per cent between 2022 and 2023, with 1,706 deaths recorded in 2023.

Shane said expecting decriminalization to reduce overdose deaths is using the wrong measure of success.

“People who use drugs were really vocal during the implementation of decriminalization that the metrics have to be correct,” she said. “You have to be measuring success by decreased police interaction, decreased incarceration.”

But according to the Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions, there is a strong link between police seizures of drugs and fatal overdoses, and research has shown “that drug seizure was associated with having administered naloxone to reverse an overdose.” The ministry’s statistics show that decriminalization did result in a much lower rate of both seizures and drug possession charges.

Data from the ministry shows that the number of drug seizures dropped from 1,283 to 86 between 2022 and 2023. Drug users and advocates have said that when police seize drugs, people who use drugs often turn to risky sex work or criminal behaviour to be able to replace those lost drugs and stave off painful withdrawal symptoms.

Since decriminalization, possession charges have dropped by 77 per cent, compared with the previous four-year average.

In his April 26 press conference, Eby acknowledged that addiction should be treated as a health problem, not a criminal justice issue. He said that years ago as a junior prosecutor he had prosecuted a young Indigenous woman for drug offences and described the experience as “the worst day of my life.”

“She left that courthouse worse, after taxpayers paid how much money to prosecute her,” Eby said.

A catch-22 for drug users

If Health Canada agrees to Eby’s request, where does that leave drug users?

Shane said homeless people will be left with nowhere to use drugs without fear of an interaction with police.

“You’re being told that you cannot be here or here or here or here, and you’re not given any other options in terms of where you can go,” she said.

“The result is that people are going to default to the alleys — the hidden locations where the risk of overdose is higher and the risk of death is much higher, because you’re invisible.”

If that homeless drug user is in the Downtown Eastside, there are numerous overdose prevention sites where they could use drugs without fear of arrest or having police confiscate their drugs.

But if that homeless person lives in any community north of Campbell River on Vancouver Island, or in most towns in northern B.C., the Kootenays and the Okanagan, there is no other option for decriminalized drug use.

Most other towns and cities that do have an overdose prevention site have just one location, often open for limited hours.

Shane said the Harm Reduction Nurses Association lawsuit includes another important component: a request for a court order to force the province to fulfil a ministerial order from 2016 on overdose prevention sites.

That ministerial order, signed by then health minister Terry Lake, “gives BC Emergency Health Services and regional health authorities the ability to provide overdose prevention services as necessary on an emergency basis.” The order says it is the responsibility of each individual health authority to assess the need for such sites in their region.

But eight years after that order was put in place, access to overdose prevention sites across the province is spotty.

Shane said the HRNA lawsuit will continue to proceed through the court.

When it comes to hospitals, the B.C. government says drug use will be permitted only in “designated medically supervised addiction treatment areas.”

But Gear said she knows of only one such treatment area, at St. Paul’s Hospital in downtown Vancouver.

Gear said that health providers can treat patients for withdrawal symptoms for a variety of substances. But she acknowledged that if Health Canada agrees to the B.C. government’s request, patients who continue to use illicit substances would have to use drugs outside of the hospital.

But unlike smoking a cigarette on the street in front of the hospital, patients who use illicit drugs would now be at risk of arrest.

“That’s not really solving a problem,” Gear said. “So our role now is to ensure that there is advocacy for safe consumption sites.”

With files from Andrew MacLeod and Michelle Gamage. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: