[Editor’s note: This article runs in a new section of The Tyee called ‘What Works: The Business of a Healthy Bioregion,’ where you’ll find profiles of people creating the low-carbon, sustainable economy we need from Alaska to California. Find out more about this project and its funders.]

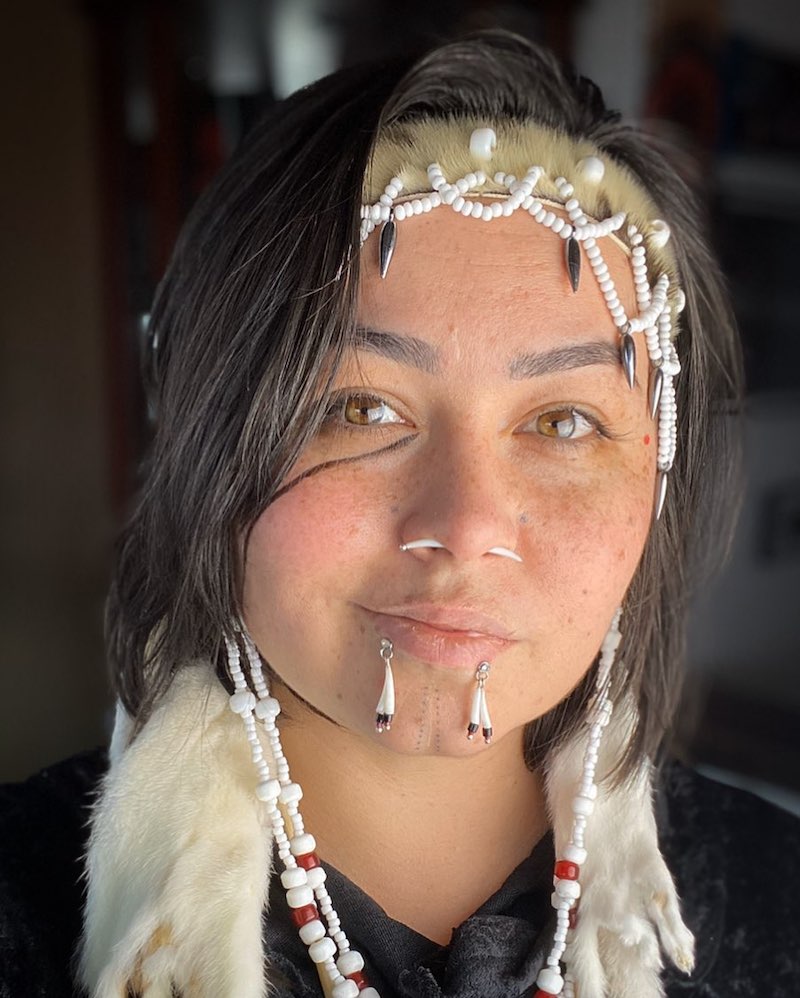

Fish leather artist June Pardue began her journey into the craft not knowing where to start. Which was a problem, considering that she had been given the job of demonstrating for tourists how to tan fish skin at the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage. “I couldn’t find anyone to teach me,” Pardue said with a laugh.

“One day a guy from Mississippi noticed me fumbling around. He kindly waited until everyone had left. Then he said, ‘Do you want me to share my grandpappy’s recipe for tanning snake skins?’”

His cocktail of alcohol and glycerin allowed her to soften the skins — as tourists looked on — for future use in clothing and bags. This worked fine until she began to grow uncomfortable dumping toxins down the drain. Now she uses plant-based tannins like those found in willow branches after the season’s first snowmelt. She harvests the branches gingerly, allowing the trees to survive for the next generation of fish tanners.

Pardue, who teaches at the University of Alaska, was born on Kodiak Island, off the southern coast of the state, in Old Harbor village. Alutiiq and Iñupiaq, she was raised in Akhiok, population about 50, and Old Harbor.

Following her bumpy start at the heritage center, Pardue has since gone on to become one of Alaska’s and Canada’s most celebrated instructors and practitioners in the field of fish leather, lighting the way for others in Alaska and Canada.

Among the people Pardue has advised is CEO and founder of 7 Leagues tannery Tasha Nathanson, who is based in Vancouver. She met with Pardue to share her idea of creating a business built on making fish leather into boots and other items for a large customer base.

“Cow leather has been done. The future lies elsewhere,” Nathanson said.

“Now the work ahead of us is how to bring this product into the world in a sustainable manner.”

Pardue said that she supported Nathanson’s large-scale vision, appreciating her commitment to using a non-toxic, plant-based tanning process. “I wish her all the success.”

Before making her move to open a business, Nathanson spent a year running the numbers, she said. In 2022, the global fish leather market was valued at US$36.22 million. As fish tanneries open their doors and fashion houses take notice, the number is expected to grow 16 per cent annually, topping $100 million by 2030.

“Salmon certainly don’t come to mind when you think of tanning, but people are catching on,” said Judith Lehmann, a Sitka-based expert in fish leather, who took Pardue’s class. (The Tyee reached Lehmann in Panama, where she was experimenting with skins of bonito and mahi mahi.)

Growing numbers of buyers are willing to pay for not only the beauty but also the remarkable durability fish leather can offer. California-based eco-fashion designer Hailey Harmon’s company Aitch Aitch sells the Amelia, a teal backpack made of panelled salmon leather, for $795.

One company in France has started to collect fish skins from restaurants — material that would otherwise end up in trash cans — to make luxury watch bands and accessories. Designers like Prada, Louis Vuitton and Christian Dior have incorporated fish leather into their lines. Even Nike introduced running shoes made of perch skin.

Whether they know it or not, today’s trendsetters are rooted in ancient history. “People have been working with fish skins for thousands of years,” Pardue said. “Ireland, Iceland, Norway, China, Japan — it’s an age-old practice.”

Stretch a band around the globe bounded by about 57 and 65 degrees of latitude and in many of its countries you will find traditions of harvesting, scraping, drying, tanning and sewing cold-water fish skins.

That zone includes Alaska and Canada, where people have been producing fish leather for millennia. By the light of seal oil and whale oil lamps, over the long winter nights, fish skin would be stitched into layers adapted for hunting blacktail in the rainforest, or otter from a baidarka. As they harvested salmon, Inuit, Alutiiq, Tlingit, Yup'ik, Athapaskan and Salish peoples worked out of the larger concept of respecting the harvest, and using each part of the fish to ensure it returned every year.

The finished skins offered a versatility not unlike a Scottish tartan. In the north, the scales of the fish made criss-cross patterns that created traction on the snow or ice, while farther south, the lightweight impermeable coats made ideal raincoats and windbreakers for the more temperate weather.

Today Alaska and British Columbia are home to a concentration of some of the world’s last wild salmon runs. Though some populations have declined — king salmon, for example — other populations have increased. In 2023, Bristol Bay in southwest Alaska had the largest sockeye return in recorded history, a record 79 million fish.

For every 2,000 pounds of fish fillets, 88 pounds of skins can be collected. Taking Bristol Bay as an example, with each sockeye providing between one and two and a half pounds of meat, this means more than six million pounds of fish skins could be collected as byproduct from the processors in the area.

But newcomers to the growing fish leather industry should be aware of all that came before, cautioned Andrea Liu, who runs 0CO2, an artisan fish leather project based in London and Dublin.

Liu is acutely conscious of her position as a designer and a non-Indigenous person working with a “highly sacred Indigenous craft.”

“Understanding positionality is important with this topic of fish leather,” Liu explained. “Many do not realize how loaded the topic of fish leather is.”

Liu first started working with fish skins in 2017. Since then, she said, she has travelled to Iceland, Sweden, Alaska and British Columbia to meet elder gatekeepers of the tradition.

“I've learned through my mistakes how important it is to include the voices of the First Nations artists who work with this sacred material — whether it's through my writings, speaking and making. There is depth to the material, and a realization that when working with salmon skins it goes beyond craft and into a learning curve of understanding where this material comes from.”

In other words, the creation of fish leather pulls makers into a larger story that should be recognized, honoured and — due to colonialism — mourned. “For those of us who are working with salmon skins and do not hold a blood tie with the First Nations, we are indebted to First Nations women,” Liu said.

“The study and understanding of this topic require a journey of finding out what it means to decolonize our methodologies as designers, makers and producers.”

Fish leather maker Hanna Sholl, who is Sugpiaq/Alutiiq, lives on Kodiak Island, where she was born, with her husband and four children. She sees the revitalization of her heritage as her life’s work. She crafts traditional regalia and teaches methods to adults and children.

“For Alaska people, salmon is part of our life. We have legends and stories. So much revolves around the fish.”

Sholl explained that with the arrival of the Russians in the late 18th and 19th centuries, otter fur was quickly hunted out — first along the southern coast of Alaska, in Prince William Sound and around Kodiak Island, then along the Alexander Archipelago, the cluster of islands connecting Canada and present-day Alaska.

“This was a period when so much of our knowledge was put to sleep,” Sholl said, noting that in the days of colonialism, Russians barred the Alutiiq from wearing traditional furs.

“We would traditionally be wearing bearskin and sea otter and seal, and maybe there would be bags or accessories made of fish skin. But fish skins didn’t catch the appeal of people who were there for fur trading. So they weren’t traded or confiscated, and thus became an important resource.”

The looseness of a fish skin parka allowed body heat to be captured and retained, while the thinness created a lightweight and versatile covering. The cloth could also be stretched into blankets, windbreaks and even tents, with the hood draped over an ice pick, and stones pinning the sides to the ground.

As colonizers decimated species that Indigenous communities relied on for food, fish leather could even be eaten for survival. Fish tanner and teacher Karen Denise McIntyre remembers her Yup’ik grandmother telling of “times when the fish runs were low, and times the game didn't return. And during those times my people faced starvation because of the overharvesting of sea mammals for their oil and fat to light the streets on the East Coast.

“Grandma said in tough times our people were forced to eat their clothing like their shoelaces made of hide, and also items made of fish skin.”

Born in Nevada to a Yup’ik mother and an Irish father, McIntyre came to Bethel, Alaska, at the age of 21, where her father worked in the Red Devil mercury mine, and later moved with her husband to the coastal town of Sitka, situated in the Tongass rainforest, the largest intact temperate rainforest in the world.

Shortly after the move, she took a class at Sitka’s Sheldon Jackson Museum, named for a missionary who came to Alaska in 1877. Jackson had a lifelong interest in fish skins. “The Natives [of Kodiak Island] made shirts out of the skins of codfish and salmon,” he wrote. Back home in Sitka, where he established his school, he began a collection of garments made of fish leather.

McIntyre said taking that class changed her life. “That is where I learned how to work with fish skin, and where I became familiar with the objects of our ancestors. I saw in person just how brilliant we are.”

And she learned an interesting fact. The head of a fish holds just enough brain — with just enough lecithin — to naturally tan a hide. “Isn’t that strange?” she joked. “All animals have brains just large enough to tan their own hide.”

She described how, once the tail and guts and perhaps brain are removed, the skin is flensed. A dull ulu, or even a bone or seashell, is used to scrape any remnants of flesh with care not to rip the skin.

Historically, before tanning, the skins would be soaked in urine for one or two days to remove excess oils. According to Rita Blumenstein, a tribal doctor, the Alutiiq used urine from an unweaned baby. (McIntyre further specified she had heard the urine should come from a boy.)

Once the fish skin is ready for tanning, McIntyre explained, most contemporary fish leather producers use “veg tanning,” incorporating plant materials (like the willows harvested by Pardue) to finish the skin instead of “chrome tanning,” which employs the chemical chromium sulphate to soften the skin.

“Cowhide generally uses chrome,” Nathanson noted. “But that’s already becoming nearly impossible to do in Canada because of regulations, and I would say that’s how it’s going around the rest of the world as well.”

Sholl, for example, uses Dawn dish soap, egg yolks, rubbing alcohol, salt and water as part of her 10-step process. “It just turns out that the best and most gentle way to get fat and protein out of the skins was Dawn dish soap. There you have it,” she said.

Like McIntyre, Nathanson prefers tannins from hemlock bark, largely because of their effectiveness and availability, the warm red colour released into the skin and the “fresh-sawn wood” smell.

“We have the byproduct from fish meat. And you get the byproduct from logging, which is the bark. Put these two waste products together and you have your fish leather.”

After the tanning process, McIntyre uses Mason jars to dye the skins, avoiding aluminum pots because of their reactivity. For the dye itself, she uses blueberries, avocado pits and beets, attaching the fibre to the colour with cream of tartar. To mix the dye, she uses “God’s water” sourced from one of the many waterfalls on the island.

“No water from the tap,” she said. “Everything must be clean.”

The result is leather that is nine times stronger than cow leather — a strength that derives from its physical structure.

“On a molecular level, fibres in fish leather are cross-hatched, as opposed to cow leather, which is just parallel,” Nathanson explained. “So, pound for pound, this leather is stronger, which is great for shoes. And it’s more available, and eco-conscious. It’s a win across the board.”

Nathanson believes the time is right for someone in Canada or Alaska to start a high-output commercial operation.

“Please forgive the pun, but fish leather right now is an idea that needs to be scaled up. What artisans are doing is sweet, but it’s [done with] buckets in the kitchen. Artisanal is wonderful because each time you make your product it’s a bit different. Commercial is the opposite — it needs to be of consistent quality, the same every time.”

Shortly after she incorporated 7 Leagues in June 2019, Nathanson said, the French clothing designer Lacoste — the one with the green crocodile logo — contacted her for a large order. While she didn’t have the capacity then, she plans to be able to meet a large order in the future. “I’m setting out to make an impact in how an industry is run.”

Bringing 7 Leagues items to market will take another year and a half of further research and development, estimates Nathanson.

To test one of her central products, fish leather boots with heels fashioned into fish tails, Nathanson wore a pair every day for six months, she said. At the end of the period, the boots, scuffed and darkened to a burnt sienna, were displayed in a glass case at a Vancouver public library.

“It turns out they’re very sturdy,” Nathanson said.

Sholl takes a warier approach to the prospect of ramping up production of fish leather products. Mindful of her responsibility to the traditions she has inherited from her Sugpiaq/Alutiiq predecessors, she said she cares deeply about fish leather as a vehicle to heal from the wounds of the past and chart an alternative future.

“At the end of the day, I don’t want this knowledge and practice to disappear,” Sholl said. “Though, the way things are going, it doesn’t look like it will.”

That hopeful outlook is shared by McIntyre. “Fish leather is beautiful. It’s also sustainable and, in Alaska, local. Our ancestors knew that. It kind of has it all.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: