People regularly flow through the O.U.R. Ecovillage. They come from all over the world to do internships, to volunteer, to learn how to make natural buildings out of cob or design permaculture gardens. The unique blend of zoning at the village allows for experimentation with materials and technologies that would be too difficult or unsafe to test out elsewhere.

The potential for experimenting with alternative systems is what drew Ian Ralston, an engineer who specializes in developing sustainable sewerage systems in B.C. to the site, which is run by a non-profit and co-ops. Ralston wrote the recent Manual of Composting Toilet and Greywater Practice published by the BC Ministry of Health and co-authored the BC Sewerage System Standard Practice Manual. He credits his experience at the O.U.R. Ecovillage, located on 25 acres just east of Shawinigan Lake on Vancouver Island, with helping him to figure out the practicalities of those standards.

“[Experimenting at O.U.R.] has been useful for working out levels of complexity and need for maintenance,” he says. “For example, humanure is simple, but too maintenance-heavy perhaps for cities, but other forms [of waste treatment] require less human intervention.”

Alternative wastewater treatment systems, like the one Ralston has implemented at the village, could address the harmful ecological impacts of water treatment systems in Vancouver. The current setup for Canada’s third largest city starves the hydrological system by whisking water away to treatment facilities. Heavy rainfall causes those whisking channels to overflow, which in turn causes raw sewage and stormwater to flood the area and run off into local waterways. While alternatives exist, incorporating them into urban centres like Vancouver remains a challenge.

I wondered whether demonstration sites, like the O.U.R. Ecovillage, could serve a useful function for cities, not just by working out alternative systems like wetlands wastewater treatment and demonstrating their safety, but also by determining what it would take to make widespread application feasible. I spoke with several urban planning and design experts in the region to get their perspective on the importance of demonstration sites for finding sustainable solutions.

An example of experimentation

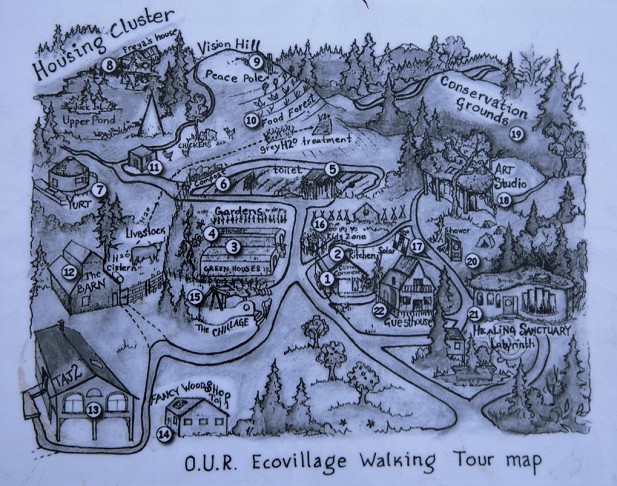

Ralston’s treatment system at the village sits on a hill overlooking the greenhouses and permaculture gardens and the smooth, rounded walls of the cob buildings that dot the landscape below. There are chicken coops on one side and a fenced barnyard with a cow and several goats on the other. When I visited, there were approximately 30 people at the village, although only 10 live there permanently. The others, volunteers and interns, sleep in tents in the forested conservation grounds at the back of the property, or in a 40-bed dormitory above the community commons building.

That building is the main meeting area for the village and contains the kitchen where shared meals are prepared by the volunteers on a rotating basis. Ralston says that four years ago, when the building was constructed, he volunteered to engineer the treatment system that would filter the water from the building.

Water from the kitchen receives aeration pre-treatment before combining with the rest of the grey water in septic tanks by the building. The water sits in the tanks to allow solids to settle out before the grey water and a little bit of effluent from black water septic tanks is piped a short distance up to the wetlands. The water then fills beds of gravel in those wetlands that are covered in a biofilm of bacteria and organisms and stays in contact long enough for those organisms to consume impurities. It then drains into subsurface drip irrigation that waters the fruit trees in the orchard at the back of the property.

This system not only provides a high level of treatment using low levels of energy and complexity, but it also generates a habitat that can be beneficial to other plants and animals. Ralston says wetlands systems are also more effective than other systems in the treatment of dangerous contaminants like hydrocarbons and chemicals used for airport de-icing.

Ralston has given several presentations at the village and says that understanding how waste gets treated and the effect the treatment has on the environment is important.

“It has beneficial socio-cultural effects that are hard to quantify. It makes people aware of and connected to how their wastes become resources,” he says. “It’s healthy for people in general to be in control and to understand what’s happening in their environment.”

Wetlands wastewater treatment facilities are already used in many cities and towns including Arcata, Calif., River Hebert in Nova Scotia and Niverville, Man., but Ralston says B.C. has fallen behind on wastewater treatment. Municipal regulations in the province are not favourable to installing wetland systems.

The problem with city infrastructure

While Vancouver is a leader in many sustainability initiatives, Larry Beasley, retired co-director of planning for Vancouver who now writes, teaches and serves on the board for TransLink, says that the need for changing water treatment in the city has only recently been acknowledged.

“We were focused more on restructuring the city for density and diversity,” he says. “We didn’t realize that we also have to restructure the use of energy, the management of waste, handling water, the availability of all the components of production, food, the locality of all that. Around the whole world we’re learning slowly, what is a sustainable city?”

Part of what makes change so difficult in big urban centres like Vancouver is that vast infrastructure systems are already in place. Patrick Condon, a frequent contributor to The Tyee who recently ran for mayor and has over 25 years of experience in sustainable urban design, says it is not as easy as identifying a problem with existing infrastructure and finding alternatives. It takes a lot of money and political support to orchestrate widespread change to something like the wastewater treatment system in Vancouver.

“Once you've devoted 100 years or more into that system,” he says, “it’s very difficult to change. It would require a huge reinvestment, you'd have to abandon the existing system for the most part that you've spent many billions of dollars building and maintaining, and it would require huge increase in taxes. That’s unlikely to get political support.”

While Condon explains that Vancouver has made progress by implementing distributed stormwater management systems that channel rainwater into ponds, he says that to correct the harmful impact cities like Vancouver have on hydrological systems the changes need to be adopted across the system.

“It doesn't do any good to do it on one yard really,” says Condon. “It has to be done watershed-wide, and the only people who can do that really are the city, through policies and the way they engineer the road systems.”

Beasley agrees that cities are designed to improve what they’re already doing instead of changing directions, but he sees the potential for gradual change by implementing progressive policies that will be carried through the ever-shifting roster of elected officials and governing bodies.

“I think what we all have to do is look at this in a multigenerational, organic way,” he says, “meaning everywhere that we can start progressive moves we need to do that. And that’s why plans like Vancouver’s Greenest City Action Plan and TransLink’s Green Transportation plan are so important because they start us early to make many kinds of changes that go beyond the direct objectives of sustainability to help restructure the city.”

Zoning for sustainability

The BC Climate Action Toolkit — an intergovernmental resource intended to provide tools and strategies for reducing greenhouse gas emissions to the B.C. government — recommends pre-zoning or rezoning in order to encourage the implementation of more sustainable alternatives. I asked Beasley what this would look like. He said that zoning is important in that it can specify how development is allowed to proceed.

“With zoning, you can set up a very progressive framework of public expectations for the performance of a developer and it can have all the different aspects of sustainability built right in if you want to. In my whole life I’ve been taking zoning and building all the most contemporary ideas right into it.”

This is what the city has done for encouraging green buildings that meet LEED energy efficiency standards. While it would be too difficult and expensive to mandate retrofitting all existing structures to live up to these standards, all new builds and rebuilds are expected to do so. This allows for a slow shift towards sustainability that is manageable in a complex urban system.

While it may not be feasible to replace the vast wastewater treatment infrastructure with distributed treatment all at once, new systems could be implemented by requiring future developments and rebuilds to make use of distributed wastewater treatment facilities.

Ralston points out that making use of distributed systems can also bypass regulatory issues.

“If you keep them small enough here in B.C. you can avoid municipal wastewater regulation entirely and use the sewerage system regulations, which are way more flexible and will allow for systems that will perform better,” he says.

The importance of testing new systems

Before requirements that allow this shifting to occur can be mandated, however, new systems must be deemed safe.

Frank Ducote, senior planner and senior urban designer for Vancouver for over 11 years before going into private consultation, recalls the infamous “leaky condo” fiasco in the 1980s and 1990s as an example of what happens when regulations get it wrong.

A new national building code was developed for Canada based on a cold, dry climate. For most of Canada, the envelope that was designed for walls included in the code prevented cold from getting in or out, but in Vancouver’s wet, cold climate, that pocket trapped condensation, leading to rot and mould. That and a variety of other factors involved in construction and regulatory oversight caused damage to thousands of homes and resulted in massive lawsuits against builders and developers.

Determining the safety of a new material or service is not the only reason for testing before implementation. Ralston stresses that when experimenting with new technologies, it’s important to focus on process.

“If you’ve got a complex system for greywater recycling installed in an apartment building and something goes wrong,” Ralston points out, “is the plumber that comes in going to know what to do with it? Who is going to service that?”

This is part of the complex reality of cities — you can’t simply install a new system or new technology and leave it to do its thing. You need to work out the institutional and societal implications and educate service providers to monitor and maintain them.

Ralston says he learned this first-hand at the O.U.R. Ecovillage. Swept up in the potential of the wetland water treatment model, he didn’t put much thought into whether the labour force there could sustain the project. Because the village relies on volunteer labour and people regularly come and go, ensuring that there is always someone there with the capacity to keep the system going is tricky. Ralston says when the one person who knew how to maintain the wastewater system left, the project was largely abandoned — not because it wasn’t working, but because there was no one there to maintain it.

The danger, says Ralston, of focusing too much on the technology side of things without emphasizing process is that you end up with a technology that isn’t effectively sustained. That can look like a failure on the part of the technology.

“If the technology is implemented without that and it is disastrous,” he says, “that may lead to conclusions that the technology itself isn’t viable, or safe. It can result in abandonment of what may potentially be very useful.”

He’s now experimenting with smaller-scale bark mulch treatment facilities on the property that will be simpler and easier to maintain and will back up into the main wetland treatment system if something goes wrong.

Demonstration sites for testing

Not only do demonstration sites allow for the safety of a new technology or system to be established and the process elements to be worked out, they can also serve as an education site where those who will be responsible for installing and maintaining them can learn how it’s done.

The urban designers I spoke to pointed out that testing sites don’t need to take the shape of an actual separate village but can be done in designated sections of the city.

Beasley says Vancouver is well-positioned, given its many separate city centres, to test out alternative technologies in pockets of the region. He pointed to the Athlete’s Village as an example of such a site within the city.

“I think the whole region can learn from the research that’s been brought together in order to create that blueprint, so I think we could do many of those different experiments,” he says. “I’m also a great believer that even a small experiment can have a powerful change in people’s consciousness and lead to much more excitement about other experiments.”

Part three of three in our series “Experimenting with Sustainability.” You can view all the stories in this series here.

Read more: BC Politics, Municipal Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: