Does planting a tree equate to meaningful action against climate change?

It projects hope and sends a message to the next generation. A tree can live for 500 years, not only storing a large amount of carbon but also enriching the air with oxygen. And it provides a home for countless species.

But well-intentioned tree-planting schemes carried out by companies and private individuals in public forests highlight an unfortunate reality — one that can be laid at the feet of the government agencies responsible for forest management.

By planting huge areas with spruce and pines, these agencies have been paving the way for an ecological disaster for decades. Their efforts have been so successful that today more than half the forests in Germany consist of nothing but non-native conifers.

This has never made sense. Even before the dry summers of 2018 to 2020, more than half the spruce — the most important species for forestry — were falling victim to bark beetles or storms. It was almost as though the industry was designed to fail in spectacular fashion, a predictable disaster in an industry bailed out time and again with tax dollars.

In Germany, when disaster strikes, both private forest owners and, of course, public forest agencies, have a legal obligation to replant trees within a few years. This means that areas planted by well-meaning individuals in their free time would have been replanted anyway. The authorities in charge, the federal forest agencies, would have made sure of that.

Volunteer initiatives often don’t even save forest owners money, because both private and community reforestation initiatives after catastrophes and the replanting of plantations are heavily subsidized.

All that remains is a gigantic public-relations operation. Volunteers are under the illusion they have done something good — and nature bears the costs as it steps back to make way for yet another plantation.

Rebuilding from the ground up

There are a few situations where planting a forest from scratch seems like a good idea. It could work, for instance, in places where there are no old trees nearby that could seed themselves — in wide-open expanses of agricultural land, for example. In places like this, natural reforestation would take longer, but natural processes at work would be fine to allow them to proceed somewhat more slowly.

Nature has plenty of time; people usually have less. If we view reforestation not only as a return to nature but as an initiative to combat climate change, then it’s okay to give nature a hand. And in many cases, planting works, especially if you plant native species, which in Germany are deciduous trees such as beeches, oaks and birches.

Even then, the little deciduous trees face severe challenges from the beginning. The first issue concerns their roots.

In nature, a 40-centimetre-tall beech has a root system that stretches out over more than one square metre. You can’t dig the little tree up and replant it without damaging its roots. And even if you could, the weight of the clinging soil would require an excavator to move the sapling and put it in the ground.

No one wants to go to such an expense to move a small tree — the process needs to be cheap and quick. Just as in agriculture, there is a race to the bottom with prices, and the result is that a small beech or oak must cost no more than 2.5 euros — including the costs of planting.

A tiny tree for as little money as possible that can be planted cheaply and quickly.

Returning to the roots

Root tips are among the most sensitive organs in a tree. As the root system must be as small as possible so it fits into a hastily dug planting hole, the roots are trimmed back at the tree nursery and often once again in the forest.

This is where scientists have discovered structures that act a bit like brains. This is where a tree decides how much to drink, which neighbour it will supply with sugar solution via the trees’ underground network, and which fungi to pair up with.

Once the tips are trimmed, these sensitive organs never regenerate quite as they were. The little trees no longer sink their roots deep into the ground and barely network with each other.

Communication — at least via their root systems — mostly stops, which leaves the infant trees susceptible to dangerous attacks by insects or herbivores.

Normally, when a tree is attacked, it uses a chemical alarm call to warn others of its species so they can prepare to defend themselves by building up their stores of toxins. It’s as though the young forest falls silent and loses its sense of direction.

Root amputation also leads to flat root systems that no longer adequately anchor trees. When the roots of native deciduous trees grow out rather than down, they no longer have access to the deeper layers of soil where the life-giving rains of winter are stored. These defects are clearly visible in areas of Germany that were newly planted in 2019 and 2020. The trees here often dried up in their first year.

In contrast, wild trees of the same age growing naturally in the immediate vicinity were resplendent in their fresh green growth despite the intense summer heat. These wild seedlings have another advantage: they are locals.

They know the climate and are adapted to the harsh realities of life in this area, unlike cohorts from tree nurseries. How could nursery trees learn to manage their water intake during a dry summer when they’re being irrigated?

Intergenerational and local knowledge of trees

Little trees from the tree nursery aren’t only missing what they could have learned for themselves, but also what their parents would have passed down to them under normal circumstances.

Tree parents pass the distillation of their life experience to their offspring through epigenetic markers. These are methyl molecules that attach to genes like bookmarks and are passed down to the next generation when seeds are formed. The seedlings then “know” how to deal with the soil where they are growing, the amount of rain that falls, and the current summer temperatures.

Forests that regenerate naturally have one more thing going for them: they are better placed to face new challenges. A beech produces an average of almost two million seeds over its lifetime, all of which have different characteristics.

Statistically speaking, only one of the seedlings will grow to maturity to replace its mother. And that one is, logically enough, the one most suited to the exact conditions it encounters where it’s growing.

Towards resilient forests

The situation is different when planting new forests on former agricultural lands. What is the most effective way to restore these ecological deserts when you want a forest to grow as quickly as possible?

It’s very simple. All you need to do is simulate natural reforestation but speed the process up. You start by planting the fields with birches and aspen. These pioneer trees are among the first to settle new areas, but if there are no mother trees close by to provide seed naturally, you can help by planting these trees at a density of 500 trees per hectare. Growing as fast as one metre a year, they will quickly form a small woodland to shade the soil and keep it moist.

Waiting for nature to take action might not look particularly impressive — but the more you work with nature, the less spectacular the results.

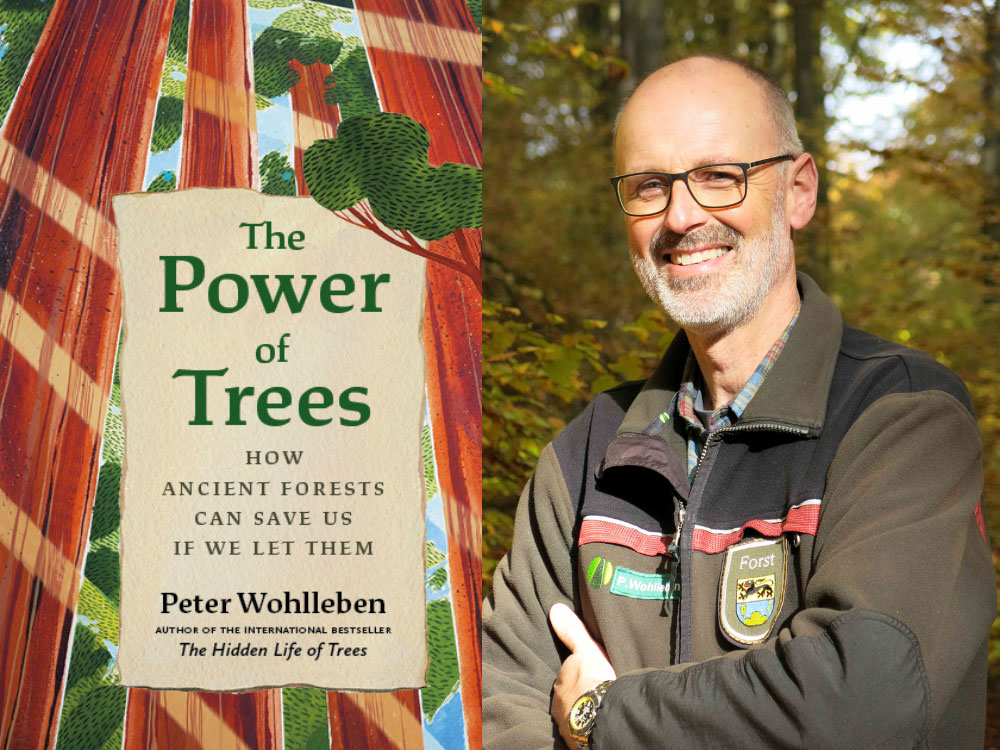

Join Peter Wohlleben in conversation with Arno Kopecky on May 7 in Vancouver, presented by The Tyee. Admission includes a signed copy of the book. Get more info and buy tickets.

Adapted with the permission of the publisher from the book ‘The Power of Trees: How Ancient Forests Can Save Us if We Let Them,’ by Peter Wohlleben, translated by Jane Billinghurst and forthcoming from Greystone Books this May. ![]()

Read more: Books, Environment

This article is part of a Tyee Presents initiative. Tyee Presents is the special sponsored content section within The Tyee where we highlight contests, events and other initiatives that are either put on by us or by our select partners. The Tyee does not and cannot vouch for or endorse products advertised on The Tyee. We choose our partners carefully and consciously, to fit with The Tyee’s reputation as B.C.’s Home for News, Culture and Solutions. Learn more about Tyee Presents here.

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: