I have had a lifelong love affair with salmon. I spent 30 years as a buyer for a large B.C. seafood processor, led several industry organizations, worked for 10 years on harvest reform for NGOs, managed a large Indigenous fishing company, and even wrote my masters thesis on Skeena sockeye.

At the conclusion of every salmon fishing season, I prepare a recap of the commercial and recreational results. However this year, despite my friends and colleagues hounding me, for months I kept finding excuses not to sit down and write. I didn’t know why I was dragging my feet. It wasn’t until I forced myself to sit down and face the blank screen that I understood the truth about my avoidance: it was too painful.

My relationship with salmon fishing began when I was a pre-teen, working for my father in Richmond. In the late 1960s, my dad was a public accountant for several prominent Japanese fishermen and boat builders, including the Atagi brothers.

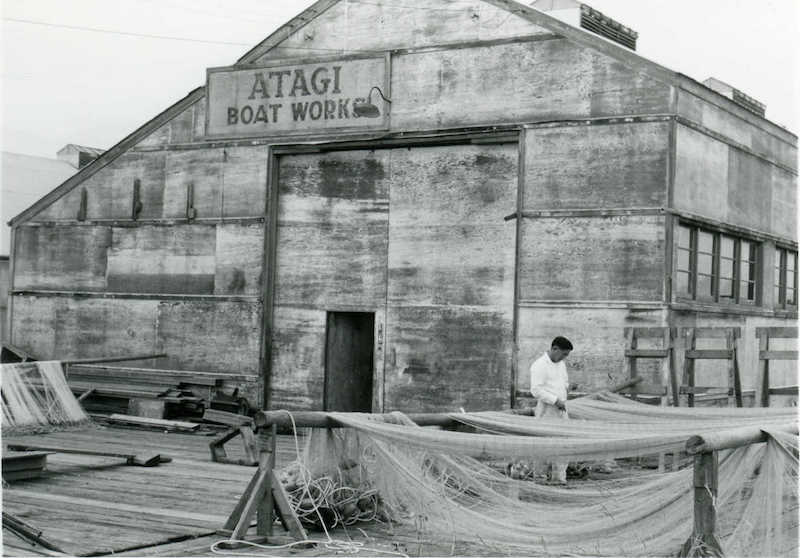

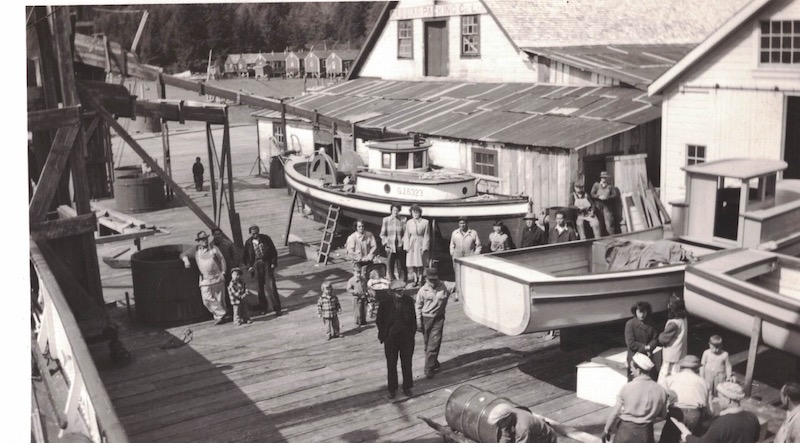

In preparation for Dad doing the Atagis’ taxes, I’d sort and reconcile a year’s worth of fishing receipts and fish tickets, usually delivered in a shoebox. I’d often ride my bike to Steveston, where their small wooden shipyard rested on the muddy banks of the Fraser River, woven into a patchwork of boardwalks, netfloats and boathouses, to collect a missing receipt or just hang out, watching Hisao, Kaoru and Kenji Atagi, quiet, slim men, build or repair a small fishing boat.

Finishing a boat is not like finishing a house: nothing in a boat is square. Everything in a boat must fit the curve of the hull while pleasing the eye. The Atagi brothers learned and honed their shipwright talents under their father Tsunematsu, who arrived from Japan in 1900. They took measurements by eye and, without writing anything down, could leave the boat and build a cabinet using skills and tools brought over from Japan. When they returned to the boat, they’d slide it perfectly into place.

Before being interned near Nelson during the Second World War, having had their boats, shipyards, and homes seized by the Canadian government, the Atagis built 32 fishing boats. Returning home after the war, they built 21 more; some of the hundreds built by Japanese boat-builders before and after the war.

In my early teens, I worked two or three summers for Stamnes Marina on the middle arm of the Fraser across the river from what is now a large hotel. Although pleasure boats were beginning to take over, many gillnetters and log salvage boats remained. Arne Stamnes, one of the dozens of Norwegian immigrants who populated B.C.’s fishing industry, lived in an old farmhouse across the street from the marina. In the late spring and early summer, he would fish "his" short stretch of the middle Fraser near the airport for chinooks in his small gillnetter. Think about this for a minute. He used to gillnet for chinook salmon. Forty-five years, or just over 11 generations of chinook later, these same populations of chinook are listed as endangered.

In 1980, I took a job at the Cassiar Cannery. Cassiar, at the mouth of the Skeena River, was the last independent isolated cannery in B.C., built in the salmon goldrush by determined Scottish and English businessmen.

Cassiar was my first introduction to First Nations communities whose lifeblood was salmon. The cannery may have been built in 1903, but the dozens of First Nations families who worked and fished at Cassiar were repeating an annual pilgrimage to their summer villages thousands of years old. The First Nations who fished the boats and processed the salmon at Cassiar were largely, but not exclusively, Gitxsan and Gitanyow, their stories and histories emanating from the proud totem poles overlooking their villages. I didn’t know it upon beginning my journey at Cassiar, but many of the prominent fishermen were chiefs, holding proud names tied to their lands and passed through multiple generations.

A fleet of Japanese fishermen also fished for Cassiar. One of my first jobs as a junior account manager was to visit them on their isolated floats and bunkhouses after the day’s fishing, traditional Japanese music wafting on a gentle breeze, rice and sockeye cooking, as they quietly spoke in Japanese or mended nets.

Cassiar in the 1980s was a living museum of coastal B.C. circa 1910. An amalgamation of people from all backgrounds, classes and communities lived close to nature, their lives guided by the annual pulses of the salmon. Everyone who worked in the salmon fishery shared the jittery excitement upon the arrival of the first sockeye in June, the heart-wrenching disappointment of a poor run, the joy in a good one, and we all spent our winters dreaming of what the next season might bring.

However, just as in early B.C., although people of different backgrounds worked together, they lived apart. Racism was woven into the fabric of life.

First Nations occupied their company-owned village adjacent to the cannery, in what appeared to me to be almost Third World conditions. Chinese men, hired out of Vancouver’s Chinatown by a Chinese man paid by the head, were rarely seen other than at work or walking between the cannery and their bunkhouse on site. The only thing I knew of these Chinese-speaking men were rumours about hard drinking, opium and entire season’s wages being won or lost. The Japanese lived a few miles downstream in a bunkhouse complete with a wood-fired communal bath. I lived with a mix of white workers from all over Canada in a separate bunkhouse upstream of the central boardwalk dividing the white section from the native village and Chinese bunkhouse. The managers lived in small cabins along the banks of the river between my bunkhouse and the cookhouse.

Michael Turner, the poet and author, who lived in a room down the hall from me, dubbed Thursday “in-seine day.” We would sit on the bull rail in the early morning waiting for the steam whistle to signal breakfast, looking out over the river shrouded down to the water in a thick mist. Slowly, the curtain of mist would begin to rise, revealing a fleet of seine boats that had arrived overnight from various north coast openings, laden with loads of pink salmon, scuppers nearly awash, the opening act for the busiest processing days of the week.

The seine boats were run by young, competitive men escaping a predictable life in Vancouver, or others from coastal communities such as Lasqueti Island, Sointula, Alert Bay and Prince Rupert following in their fathers’ and grandfathers’ footsteps.

A good proportion of the boats were run by men of Croatian heritage. The Croatians were from two waves of immigration. The first was around 1900, the second after the Second World War. Skippers of boats from the first wave golfed at country clubs, cruised the world in luxury liners, some changing from slippers to rubber boots only when they had to leave the wheelhouse. This generation revolutionized seining, inventing new fishing technology such as the power block that would reduce manpower needs and make seining much more efficient. The second wave was more rough, boisterous and tied to the traditions, food, and wine of their home country. A good season often led them to buy a second, third or even fourth small rental house in an East Vancouver neighbourhood.

For me, writing a recap of the 2019 season is a walk through an untended graveyard. The bounty of salmon that sustained it all is gone. Fraser River sockeye, where it all began, now supports a fishery only one year out of four. Fraser chinook and coho, which once supported troll fleets working out of coastal communities like Sooke, Ucluelet, Winter Harbour and Port Hardy, are listed as either endangered or threatened. Skeena sockeye is a shadow of what it was when I worked at Cassiar, kept viable only through enhancement. The First Nation gillnet fleets and the businesses they kept afloat are gone. As are Skeena pink salmon. Chums in Area 6, near Douglas Channel, an area beloved by the Croatians, are depleted, its pink returns inconsistent.

Everything — the salmon, the people, the communities — is buried under climate change, habitat destruction, overfishing and the loss of a collective memory of what was, and what could be.

I believe in salmon. I believe we can recover them. I believe we can get enough people to see what we have lost and what we could gain by gifting future generations with large returns of wild salmon. It will take a commitment of resources, a new way of thinking about development, relearning the lessons from thousands of years of successful First Nation’s management.

There are no quick fixes. The solutions are not to be found in enhancement, killing seals, or stopping all fishing. The solutions are to be found in making personal changes that contribute to slowing climate change and decreasing pollution, convincing our politicians that their constituents must be salmon, not harvesters or industries, improving stream flows, and rehabilitating habitat, especially on the Fraser River.

It will take changing our relationship with salmon, from seeing them as steaks on the BBQ or sport on the end of the line to understanding them as an investment in our collective future.

And hopefully, one day, future communities around the province can evolve and centre themselves around diverse, dynamic, and abundant populations of salmon. And they, like past generations, can experience a connection to the elemental pulses of the wild salmon's annual return. ![]()

Read more: Food, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: