[Editor's note: What one paradigm shift would have the greatest positive effect on the future development of Vancouver? That's the question asked by Shift, a recent panel held as part of the UBC School of Landscape and Architecture's fall lecture series. Fifteen architects, artists and planners presented one worldview-shifting image, and discussed its significance and potential for the city. Here are some highlights.]

Shift #1 : See transit as a net, not a web

By Patrick Condon

Presently we inhabit a very strange cultural space, where a vision of a sustainable future inspired by George Jetson competes with one straight out of The Flintstones. For example, in Vancouver our leaders are, on the one hand, loudly supportive of the Jetson's Orbit City style version of a sustainable future -- enthused about a gleaming SkyTrain all the way out to UBC. SkyTrain. The name itself excites. This is no mere mass transit system. This is a fleet of spaceships gliding effortlessly out of reach of the impediments of the street -- sleek star cruisers that slow only to dock at luminous regional town centre space ports.

But really, the idea seems a bit dated, doesn't it? A vision from a time of moon shots and jet packs. A vision from a time when energy and resources were unlimited, and Earth a cornucopia to supply our every want.

Meanwhile, many of these same officials are equally enthusiastic about a second vision of sustainability that owes more to Bedrock than to Orbit City. Backyard chickens and front-yard wheat are just the ticket here, without acknowledging that for the $3-billion price tag on the UBC SkyTrain, you could buy all the wheat fields in Kansas and half of the chicken farms in Arkansas.

Having argued this point to the point of apoplexy, I am now sure that being for or against the Broadway SkyTrain line has nothing to do with facts, or even with cost, but everything to do with how you see the world. I am now convinced that people eventually end up seeing the city in one of two ways.

They either see it as a web or a net.

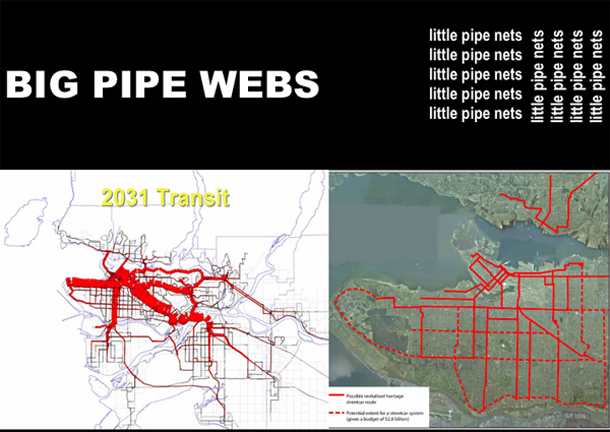

If you see the city as a web, you see it as hierarchical, with an important strategic centre and less-and-less important peripheries. In this world, you need "big pipes" to gather and manage all the energy directed towards the centre. That's why the graphic at the top is so scary to me. The one with the huge red line is a projection of the number of trips expected on Broadway after the proposed SkyTrain line goes in.

The graphic speaks for itself. It shows a 500 per cent increase in traffic out to UBC. It presumes that most of the new development in the city sits along this line within walking distance of station areas. As for the rest of the city, there is little transit growth indicated at all. As an urban designer, I find this image both frightening and depressing. It fails to acknowledge how fundamentally at variance it is with the underlying Streetcar City fabric it disrupts.

For me, this exemplifies the problem we face. I don't think big pipes are sustainable. After thinking about this for long enough to grow gray, I am convinced that the big pipe web concept of the urban region must be replaced. What we need now are little pipe nets.

We really have a limited amount of time and a limited amount of money to re-engineer our whole world for sustainability. I do not think we can do this by superimposing Orbit City big pipe webs on top of our existing Streetcar City. It's wasteful and it won't work. I also don't think we can do this by assuming we can unbuild the Streetcar City to create the room needed for enough wheat fields, chicken coops, and rain barrels to make any difference at all. They won't fit.

But if we acknowledge the inherent sustainability of the form of the city as it actually exists, not as Bedrock, not as Orbit City, but as the Streetcar City it truly is, then we might have a chance.

It seems absurd to ignore the existing little pipe framework we have inherited from the not-so-distant past. But it means thinking in unfamiliar ways. Think big! But not too big. Think small! But not absurdly small. It means reviving the little pipe net that we had and lost. It means reviving the streetcar city.

Shift #2: Close the landfill, and own our shit!

By Jennifer Marshall

If we all took ownership of our consumption, if there was no such thing as "away," if we closed the landfill... what would the consequences be? I believe it would reduce waste, reduce unnecessary consumption, and reduce unnecessary production and use of raw materials.

But it would also shift our paradigm. For one, we'd value what we have more. We'd demand higher quality, more durable goods. We'd create new industries of reuse, and foster community through sharing resources and means to recycle. Call it Craigslist on your block.

If we closed the landfill, the implications to the building industry would be profound. As the generators of 50 per cent of the landfill today, construction would be completely re-imagined. It would force industry wide change, all the way up the chain of production.

If we closed the landfill, we would literally have to own our shit!

So let's.

Shift #3: Model development on a West End wonderland

By Bill Pechet

This photograph was taken from the roof of my building, a co-op built in 1960 called the Lagoon Terrace. Located on Robson Street near Stanley Park in the West End, it's nine stories tall and contains 22 living units on a site that is 66 feet wide by 130 feet long. Like most of the buildings in the West End, it originally had one or two houses on it. The current building respects the setbacks of the original single family neighbourhood.

From my rooftop you can see a myriad of building types: three-storey wood frames, six to seven storey buildings built out to property lines, and repeated typologies of towers of varying heights, with four, six or eight units per floor. Some of these have parking pads adjacent, others have gardens, and even an occasional old house remains visible within the fabric.

This melange of housing is the product of almost 100 years of evolution, but principally, even with the radical zoning changes which produced all this density in the mid-century, the neighbourhood remains habitable, green, close to services, and recreational opportunities. Most importantly, it allows for a diversity of people: those who rent, those who own, those who are aged and those who are young.

With the pressing need to find solutions to increasing density in our city, we might benefit from looking towards the paradigm of the West End neighbourhood as a model for up-zoning strategic parts of Vancouver. Laneway housing aside, the ways in which our current models of densification are producing the endlessly repeating typology of tower clusters on townhouse podiums shortchanges the potential for these new neighborhoods to achieve experiential and social plurality.

Part of the problem is that nowadays, it is usually the rule that smaller sites are aggregated into large ones, which can't help but produce living environments of a banal and soul-scrunching character. The fact that I only live with 22 different neighbours means that I know everyone's name, feel part of a community, participate when I want in collective events, monitor the health of the older folk in my building, and even recognize next-door-building neighbours -- if not by name, at least by face.

While there is often a need and value for anonymity in our lives, the West End provides an alternative. Because its method of growth was organic, built in smaller chunks, there's a grain of intimacy still present in spite of its density. Additionally, as the development sites were once smaller than today's, the participation in development allowed for investment opportunities for different kinds of developers. Some were communities of people, while others were families or smaller-scale entrepreneurs.

My suggestion for a paradigm shift is a challenge to try and redefine the ways within which densification occurs. This new paradigm would be predicated on a free-market model which resists monolithic ownership and development, by promoting smaller scale, yet equally dense solutions for growth.

I know it's impossible to create urbanity from scratch, and that there are significant administrative hurdles -- more permits to process and squabbles about who can do what where. But it seems to me we've already achieved a kind of model for this in the West End, so a forensic analysis of how to apply similar principles elsewhere could be a goal to consider.

(I apologize to those of you who represent the development industry model of which I am critical. I don't mean to suggest that that model doesn't also have its place in the region. I love beautiful high-rises, and also know that model of living suits many people.)

I am simply suggesting there are other ways to proceed. Roughly speaking, five more West Ends dotted around the Lower Mainland would house over one-quarter of a million more people, and allow the market and flux of demographics to determine their patterns of development. That would mean experimenting with models which mix site development sizes, encouraging multiple models of development within the same block. The code written for such a new neighbourhood would need to be parametric in shape, like a flexible surface or topography of density which allows planners to proceed in a fluid manner.

I do not mean to suggest that we aspire to recreate the nostalgia of the West End verbatim, but rather that new, multi-scaled neighbourhoods built by the hands of many and not just a few is a paradigm to aspire towards.

Shift #4: Think small. New York City small.

By Dan Granirer

Building family-sized apartments in Vancouver is a major opportunity to replace the desperation over high housing prices experienced by many in the middle class, with economic dynamism, more growth in the size of young families, and hope for the future.

Vancouver is ripe for the kind of paradigm shift that occurred in New York around the turn of the 19th century, when in two to three decades, the majority of middle and upper class inhabitants of Manhattan moved from single detached homes to apartments and brownstones.

This occurred as both the city of New York and private developers successfully encouraged many people to change their expectations from raising families in houses that were becoming prohibitively expensive, to the convenience and affordability of apartment dwelling.

Construction in Vancouver of a large stock of apartments with multiple bedrooms and gracious living spaces (that came to be known in New York as Classic Sixes and Sevens) could help transform these expectations, and provide attractive alternatives for urban family living in our beautiful city.

Shift #5: Make Vancouver actually greener

By Cornelia Oberlander

Today Metro Vancouver, and so many cities around the world, are faced with unprecedented urban growth and pressures on available land. If we continue on our present course of densification, open urban spaces will become less and less available for the inhabitants.

Small parks and plazas, well-treed streets without cars for strolling and relaxing, playgrounds, bikeways, waterfronts and rooftops must be included in all developments. A new holistic vision is needed for creating open urban spaces that are safe, sustainable and healthy.

Rene Dubos said many years ago, "The concept of an optimum environment is unrealistic, because it implies a static human life. Planning for the future demands an ecological attitude based on the assumption that man will continuously bring about evolutionary changes through the creative potentialities inherent in his biological nature."

These words challenge us to re-think how we live and recreate in dense urban environments on all levels, yet providing nature experience for relieving us from stress of our daily tasks.

E. O. Wilson, the well-known scientist wrote, "The longing for nature is built into our genes," and "nature holds the key to our aesthetic, intellectual, cognitive and even spiritual satisfaction." This quote directs us to make nature accessible for all ages and abilities in well-designed open urban spaces, crucial to the quality of urban life in Metro Vancouver.

We should commit ourselves to establish a task force for public open space in 21st century Vancouver. These spaces ought to address the quality of life to which we aspire, as well as limiting footprints of developments, which will reduce our impact on the earth. These guidelines must address climate change, reduce storm water runoff, and show imaginative design, which save labour and operating expenses and choose plant material commensurate with our ecology.

This task force is to be composed of planners, architects, landscape architects, citizens, city officials, and parks officials, among others.

The Danish architect Jan Gehl says, "Basically, it is all about respect for people" -- designing the ground floor, the city at eye level, and re-ordering priorities away from cars and traffic, because everyone has the right to see a tree from their window, sit on a bench with play spaces for children, or to walk to a park within 10 minutes of their home. "We shape cities and cities shape us."

The buildings and landscapes we design today should be examples of the most advanced technology and incorporate green roofs with green balcony gardens. Then Vancouver would lead the way to being truly a green city. ![]()

Read more: Transportation, Environment, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: