During a lecture last fall, I asked my 200 undergraduate students to raise their hands if they believed they would someday own a home. Only about one in 10 thought they would.

My reaction at that moment was shame. I am one of the lucky ones. Born in the great baby boom glut of the '50s and '60s, I and most of my peers own a home.

But I fear this will not be the case for my students. Confronted with salaries that have stagnated for almost 20 years, they are faced with a housing market where the real cost of owning a home has increased by 300 per cent during the same time span.

When housing affordability is measured against average family income, Vancouver is the second most expensive city in the world, with the average home costing over 10 times our average income. (The commonly accepted ratio between average family income and average house price is four. A ratio of six is doable but crushing. A ratio of ten is considered impossible.) By this measure, Vancouver is more expensive than New York, more expensive than Paris, more expensive than London.

Vancouver baby boomers, on the other hand, are mostly sitting pretty. While our children struggle to pay high rents, never mind a mortgage, our net worth has risen to a million dollars or more just by sitting in our living rooms. And none of us want this gravy train to stop. City officials in Sydney, Australia, where similar price-to-earnings anomalies have emerged, recently clamped down on house purchases made by outside investors. In Vancouver, to even to mention such a thing is political suicide. Anyone who has bought into the system, however painful the entry fee and however long ago that payment was made, has a deep investment in ensuring that housing values continue their rapid rise.

But what is the result for our children? Well, more of them are renting than they might like. On a square foot basis, renting an apartment is a lot cheaper than buying. In many of the gleaming tower districts downtown, over half of the condominium units are rented out by their actual owners -- owners who are likely older and richer, likely living in other parts of the city, the region, the country, or the world. This disturbing inter-generational housing/affordability inequity seems even more distressing when you consider that up to 14 per cent of our downtown condos and seven per cent of other city homes sit empty, according to BC Hydro records and Statistics Canada data. Among the reasons for this vacancy is that well-heeled investors are often more interested in finding safe, simple and productive real estate investments than in the often comparatively less lucrative work of managing residential rental units.

City of lost children

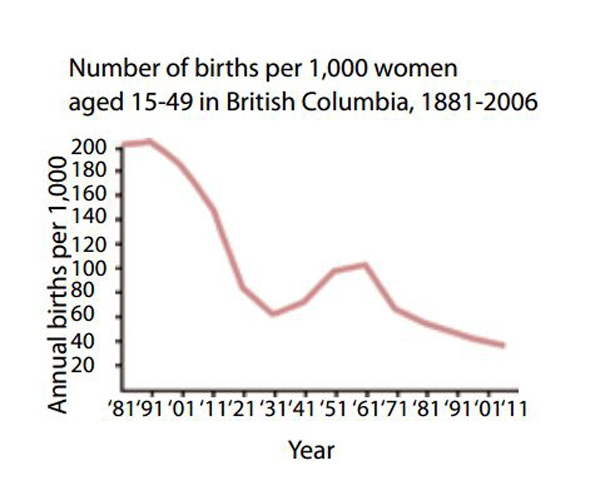

But not every trend is alarming. We are not seeing a dramatic drop in the number of Vancouver residents in their twenties and thirties, not yet. There are simply too many university slots, and too many good jobs in the city for that. What we are beginning to see are fewer children. For a long time, the city has seen a steady decline in the percentage of school-age residents. But the steady increase in our population disguised this proportionate decline, keeping absolute numbers of school-age children roughly steady and our neighbourhood schools full. But that changed between 2001 and 2010, when the number of children enrolled in Vancouver schools dropped by over five per cent. This trend seems to be accelerating, such that the Vancouver School Board recommended the permanent closing of five neighbourhood schools on the east side of the city. The hue and cry from area residents was so loud that the school board relented, proposing instead to repurpose the empty space and hope that enrollments might increase someday soon. But will they? Meanwhile the number of school-age children in Surrey continues to skyrocket, where schools are overcrowded but affordable family homes can still be found.

The east side of Vancouver, where the five schools proposed for closing by the Vancouver School Board are located, is particularly stressed. Why? The Dunbar area is even more unaffordable than the east, but its school-age children numbers are holding steady, likely because it is a preferred area for families at the higher income levels. But what is the income demographic of families who can and will spend over a million dollars for a home in other parts of the city? Why not move to Burnaby or Coquitlam instead? At this point it becomes all speculative, and we can only wait for more data from Statistics Canada. But the trends are unhappy. If the loss of school-age children is not reversed by 2050, should we expect to lose 5,000 more school-age kids? How many schools worth of kids is that? A dozen? More?

Meanwhile, for over 30 years the number of residents of the city over the age of 65 has not changed much, so we have experienced no pressure to find extra space for them. But, in the same 30 years the absolute and proportionate number of residents between the ages of 40 and 65 has more than doubled, correlating with the aging of the baby boom generation. Unless these 100,000 plus folks all move to Sun City Arizona, we can expect the absolute and proportionate number of elderly in our city to also double, and fast.

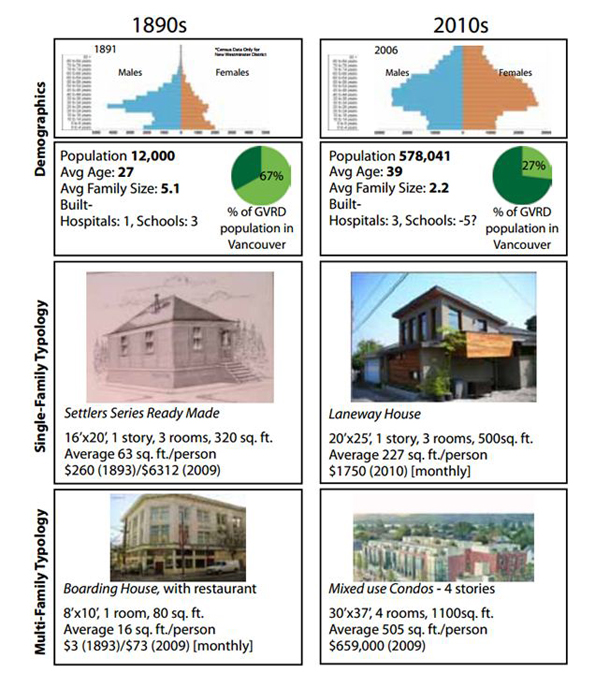

When we put all of this information on the table it made for a depressing afternoon. But after a few days of conversation and careful study, we became increasingly more hopeful. What we discovered was that in each generation, Vancouver has rebuilt itself to respond to some huge demographic shift. Back in the 1890s, when the city was first getting started, the population was mostly young men. The housing? Small one-person one-room frame homes and rooming houses predominated: a city for lumberjacks. By 1920, when women finally arrived in large numbers, the Craftsman-style home predominated, each containing many bedrooms for all the children women of that generation would typically bear. After a lag for the great depression and the Second World War, the baby boom hit and the city took off again. This time the smaller, more affordable bungalow style predominated, a starter home with room to expand. After the baby boom ebbed, things got more complex. During the '70s the "Vancouver Special" style predominated: a way to make housing more affordable for smaller families and to integrate new waves of immigrants. We are now in a period where the single family home is being broken down yet again, this time into three units, for the even smaller families now common. Now, parcels where five to seven people once lived in one family are home to five to seven people in three families.

Seeking a home for all

So how do we understand these organic trends and take the next step forward? How do we find space for our kids and our elderly so our community stays a real place? We came up with four basic strategies.

Four units per typical lot. Under present economics, it is just barely possible for the average two-income family to purchase a million dollar home, but only if they have two units to rent out. In most parts of the city, current regulations prohibit subdividing these three units into strata units. This prevents two of the three families from sharing any equity benefits as home values rise. This should be changed as soon as possible. But this is only part of the solution. Given the average incomes in our city, the numbers work out much better if there could be four, not three, units per lot. Given current land prices, this would make it possible to purchase your own two or three bedroom home, with a small garden, in an established neighbourhood, close to schools, for under $500,000. There is a second important benefit as well. Permitting four strata units per lot would allow elderly single family home owners to stay in their home as it is renovated, while liquidating two-thirds or more of the equity they have accrued. Imagine what a benefit this could be to them or their children.

Family-oriented mid-rise housing. A second opportunity for family housing is in the mid-rise category. Certain forms of mid-rise housing can be extremely family friendly, with individual access to protected exterior space, close to existing schools and services -- and, importantly, purchasable for under $400,000. Mid-rise structures at the Arbutus walk project already give an indication of how well this form can accommodate families. Many existing four-storey mixed-use buildings lining our arterial streets already hint at these same possibilities, with elevated enclosed second-storey play areas, private terraces and gardens a feature of better projects. The current cost of land is making it difficult for developers to profitably provide this type however, probably requiring allowances for higher than four stories in some parts of the city.

Shift elderly into nearby homes on arterials or age in place. In addition to the possibilities for aging in place in renovated single family homes, the elderly might also move their equity into a new nearby home. The students recognized that transit served arterials are never more than a five minute walk from any part of the city, and are already the locations for most clinics, cafes, and social clubs. Given the equity available to this cohort, there is a huge opportunity to induce a downsizing move to nearby locations, thus freeing up over large homes for use by sons and daughters or other young families.

Flexible schools. It was noted that schools are the centre of every community. Yet in many areas these schools are presently threatened with closings. Hopefully the measures suggested above, or others that are equally robust, would stem the flow of young families from Vancouver. But no matter what happens,our city will change, with many more elderly in our districts than we have now. Given this, the class suggested that schools might evolve. Entire neighbourhoods might be reconceived almost as "assisted care" districts, with the schools taking on a new function of providing daily meals and as a base for home care services, as well as keeping electronic watch on neighbourhood residents to avert medical catastrophe.

In the end, we had to conclude that, for the foreseeable future, high housing prices would be a fact of life. For those of us over 50, that is generally a good thing. For those of us under 35, it is currently a very bad thing indeed. We tried to figure out a way to make high home prices an advantage for everyone. We needed to find a way for current homeowners to be able to access their equity should they want to, and for entry level homeowners to start capturing some equity of their own. The only way we could see this happening was to change current policies yet again, upzoning all R-1 parcels currently approved for three units (one principal ownership and two rentals) to an allowed four units per parcel (four strata units or three rental units or some combination).

This would allow seniors to age in place if they chose but capture their equity in a way they now can't. With this cash in hand, they can either bank it or use part of their gains to purchase a new unit still within their neighbourhoods. For a variety of reasons we felt that the most obvious location for that smaller home was on or close to the city's many arterials, where services were abundant but families were still close by. Finally, a relatively new type of affordable family home might emerge, also on or near the arterials but designed in such a way to have protected play areas incorporated into the architecture.

Next Wednesday: What place is this? Protecting the things we love about Vancouver in chaotic times. ![]()

Read more: Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: