"I'd strike the sun if it insulted me." -- Captain Ahab

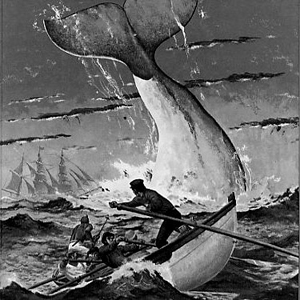

A couple of years ago Robert Wagner Jr., a well-known Houston energy banker, read the famous novel Moby Dick by Herman Melville, a former whaler. It's a rambling and gritty tale about the 19th whaling industry and America's first energy boom.

The narrative, which richly details the nature of an economic obsession, squarely harpooned Wagner, a good friend of the late energy critic, Matthew Simmons. "I was blown away by the synergies and the comparisons of whaling with the oil and gas industry, " says Wagner.

For more than 40 years the 69-year-old banker financed Texas oil deals and had a front row seat to the world's most volatile commodity while working for the likes of Bear Stearns and Arthur Andersen.

And so the maniacal pursuit of a white whale to illuminate North American homes haunted Wagner. It also reminded him how every age irrevocably passes into another whether people are prepared for change or not.

"The rampant obsessive exploration, production and consumption of hydrocarbons that saturates our society today can be read much like the situation for the men on the Pequod," notes Wagner. The world of "There she blows" and "Give it to him" actually led, if not descended to "Drill, baby, drill."

In fact Wagner found the parallels so striking that he self-published his Phd thesis on the topic: "Moby-Dick and the Mythology of Oil." It's a mighty admonition about the petroleum age and the impact of improbable events. Paired with Philip Hoare's magnificent book The Whale, the two accounts offer some rather surprising observations about human energy production and consumption.

Modest beginnings

Now the whaling industry began modestly enough in the 17th industry as source of meat, industrial lubricants and other sundries. But it was pretty much a local affair. Basque or American whalers hunted right whales close to shore in shallow waters.

But then a Sephardic Jew and American immigrant discovered that spermaceti, the waxy oil from the giant head of sperm whale, made a brighter, cleaner and harder candle than animal tallow or bees wax.

The innovation sparked a change in consumption habits and soon lighthouses, street lamps and public buildings were burning whale oil or whale candles. Wealthy urbanites abandoned home-made tallow candles, and demand for the whale's brilliant illumination exploded from London, England to Lexington, Virginia. The spermaceti candle even set a new light standard: the lumen.

"They afford a clear white Light; may be held in the Hand, even in hot Weather, without softening," wrote Benjamin Franklin. "They last much longer and need little or no snuffing."

From the beginning Americans dominated this new trade the same way the United States, the world's first petro state, later monopolized petroleum production until the 1970s. Pious Quakers with names like Starbuck, Folger and Coffin mostly managed the business from Nantucket Island.

As these Bible-quoting entrepreneurs prospered, they opened branch plants in Hudson, New Bedford, Halifax and other busy ports. At its peak the cetacean killing business employed 70,000 people and became the fifth largest business in the United States. Two thirds of the world's whaling fleet sailed from U.S. At its peak, in the 1850s, it produced more than six million gallons of whale oil a year.

Hidden horrors

But like 21st century well-chilled consumers of petroleum, the burners of spermaceti candles had little inkling of the leviathan gore of the whale fishery, says Wagner.

When they lit their candles they did not know that former black slaves, aboriginals and Cape Verdeans murdered the world's most social animal in perilous seas of blood or that these very same working men often sailed for as long as four years for a payday.

Most candle lighters did not know that a whaling vessel resembled a 19th century Satanic mill complete with oil cooking furnaces any more than natural gas furnace users understand the industrial consequences of hydraulic fracturing on rural groundwater.

Nor did they realize or dream about whales that increasingly attacked their hunters as they become more traumatized by the deadly trade. Some bull whales even stove and rammed the boats of the oil miners with a ferocity that was distinctly calculated.

Nor did the candles shed any light on whale widows who, as Hoare writes, would sit alone in their houses "smoking opium and employing plaster dildos known as 'he's at homes.'" Candle burners, too, did not know that most of the whale carcass was wasted or left to sharks. Or that a young calf would attempt to suck on a vessel that contained nothing but the rendered scents of his parents. "The whaler was a kind of pirate-miner -- an excavator of oceanic oil, stoking the furnace of the Industrial Revolution as much as many man digging coal out of the earth," writes Philip Hoare in The Whale.

No end in sight

The cetacean economic fraternity, much like modern petroleum club, could not imagine the future and often mocked any thought of replacements. They even described lard oil or coal oil as "luminous humbugs."

But around 1846, just a few years before Melville published Moby Dick, the industry peaked. After plundering the Atlantic, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, it now chased smaller whales in colder and more extreme waters in bigger vessels over longer periods of time with fewer and fewer capital returns. Meanwhile the price of whale oil doubled.

By the 1850s the majority of the industry concentrated all of its ships in just one singular whaling grounds; the north Pacific Ocean. (Today much of the continent's petroleum industry has focused investments in Alberta's bitumen deposits or the Bakken play.)

And then the whaling trade collapsed. Abraham Gesner, a Canadian geologist from New Brunswick, played a role in its demise. In 1849 he distilled Trinidad bitumen to make kerosene.

With discovery of vast amounts of "rock oil" in Pennsylvania and Ontario in the late 1850s, kerosene soon flooded the market. Its appeal was largely economic: it took fewer people less time to refine crude into kerosene. It cost but 32 cents a gallon while sperm oil sold for $1.43 in 1862.

All in all it took 30 years for whale oil to fall out of fashion and decline into a ghost, notes Wagner. The financier now sees the petroleum industry on a similar path. Just like the whaling industry it has progressively moved from the simplest and most accessible oil fields to the most complex, extreme and expensive.

The toll on nature

At the same time the consumption of the resource has created untold ecological damage ranging from climate change to urban waste heaps. Wagner believes that "We are getting to a critical point in resource supply and ecosystem tolerance for hydrocarbon consumption." Adds the former U.S. Marine, "We need to be concerned."

Ironies abound too. Plastics made from petroleum now occupy old whaling grounds (The Great Pacific Garbage Patch) while oil tankers strike and kill cetaceans as mere obstacles to human speed.

Wagner often talks about these themes in Houston circles where many industry analysts thoughtfully consider the implications of another oil industry that once called itself indispensible. In fact the cetacean killing business remains an uncomfortable mirror for the Petroleum Age.

The stakes, of course, are higher. The world consumes 40,000 gallons a minute or 85 million barrels a day. Nearly 90 per cent of what we consume has been touched by petroleum.

Ugo Bardi, an Italian chemist, says the history of the whaling industry really teaches us two things about peak oil or the end of cheap petroleum. As sperm whales got dearer, candle buyers experienced strong price oscillations and greater instability in the marketplace. Depletion happened without a reliable or cheaper technology on the shelf.

At the end of his rumination on Moby Dick, Wagner asks a rude question. It's one that Melville posed in a later novel: do we want to become "the graceless Anglo-Saxons, who, in the name of Trade, deflower the World's last sylvan glade?"

When Moby Dick first appeared in bookstores, nobody wanted to read about the whale fishery. Nearly 50 years passed before critics recognized the book's genius, let alone its brazen revelations on what lengths humans will go for energy. And money. ![]()

Read more: Energy

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: