Canada's poster child for so-called clean energy and "the world's first CO2 Measurement, Monitoring and Verification Initiative" may have sprung a serious leak in Saskatchewan.

And it's the sort of geological and political disclosure that just might unravel plans to spend billions of taxpayers' dollars on constructing elaborate carbon cemeteries across the country, if not the world.

The story, which includes explosions, dead animals, and an international cast of characters, also raises some critical questions about transparency and the quality of government regulation in a carbon-centric economy.

Nearly a decade ago, the Paris-based International Energy Agency linked up with the Petroleum Technology Research Centre (PTRC) in Regina, Saskatchewan to study the Weyburn oilfield as a perfect model graveyard for greenhouse gases. It lies underneath 50,000 acres of flat farmland.

At the time EnCana Corporation (now Cenovus Energy) had started to flood the aging crude field with gallons of salt water and tonnes of CO2 piped from a North Dakota coal gasification plant nearly 320 miles away.

Carbon dioxide, an atmospheric climate warmer and ocean acidifier, simply coaxed more oil from the reservoir and enhanced production rates. Much of the CO2 also stayed in the reservoir.

As a consequence the IEA, the U.S. government, Alberta Research Council and 20 industrial firms -- including Cenovus -- spent more than $40 million to monitor what would become the world's largest demonstration project for storing carbon underground.

Early optimism

In 2004 the IEA declared that Weyburn was a "highly suitable for the secure long-term storage of CO2" and it could hold up to 55 million tonnes of CO2. But the site would have to be monitored for 5,000 years.

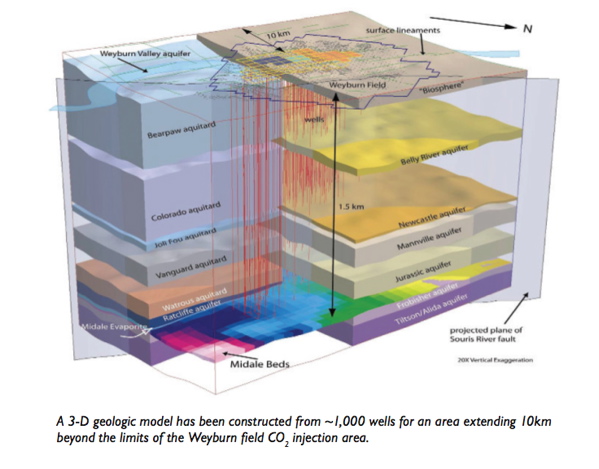

Computer risk models also predicted that CO2 would never leak into "either potable water zones closer to the surface or ground surface above the storage reservoir."

(To date more than 17 million tonnes of CO2 have been stored in the oil field, which makes Weyburn the world's largest geological CO2 sequestration project. Based on "the safety" of Weyburn, Ottawa and provincial governments have committed $3 billion to creating five or six large demonstration carbon cemeteries.)

Both the IEA and PTRC, a research group funded by government and the oil patch, also released a 283-page study in 2004 claiming there were no leaks to date and that storing carbon underground could play an important role in "tackling climate change." No real monitoring data on the project has since appeared in the public domain.

Around the same time Cameron and Jane Kerr, who own nine quarters of land in the midst of the project, started to notice some leaks.

Strange signs

For the record, the couple have 16 abandoned, producing or injecting wells within 1.6 kilometres of their land. Scientists have long noted that nearly 1,000 production and injection well sites on top of the project could act like wicks and draw up CO2 into the atmosphere.

In 2003 the Kerrs dug a gravel pit to service EnCana's oil roads. After the pit promptly filled with water, the Kerrs observed strange doings including foaming, discolouration and hissing bubbles. They also discovered the carcasses of dead ducks, a rabbit and a goat by the pit.

When several gaseous explosions rocked the pond in 2007, the couple moved to Regina. "We have a problem and no [one] wants to properly investigate it," Jane Kerr told Canadian Business at the time.

Although the Saskatchewan government promised to do a year-long study on the farm's air, water and soil, the Kerrs say it never happened. What they got instead were a few ad hoc day-long tests and nothing more.

With the help of EcoJustice, a non-profit environmental law group, and Jack Century, a retired Calgary-based geologist, the Kerrs then hired Paul Lafleur of Petro-Find Geochem to do some serious monitoring.

Unlike so-called government and industry experts intent on declaring the safety of carbon cemeteries before the evidence is in, Lafleur found lots of CO2.

Using tried and true carbon sensors designed to detect oil deposits, Lafleur discovered dangerously high concentrations of the gas on the Kerr's property.

Seeping dangers cited

In one location alone Lafleur detected concentrations as high as 110,607 parts per million (ppm), twice the amount needed to asphyxiate a person. Near the Kerr's home he also recorded concentrations of 17,000 ppm, a level "that far exceed the threshold level for health concerns."

As a consequence "CO2 could enter the home in dangerous concentrations through the crawl space due to negative pressures caused by a natural gas heating furnace."

Given that Cenovus's closest injection well lies a mile away from the Kerr home, Lafleur concluded that the CO2 was probably seeping through open fractures and faults that intersect the Weyburn field. In other words, there were cracks in the cemetery.

In addition a Saskatchewan lab confirmed that the CO2 found at Kerr's place clearly originated from "the CO2 injected into the Weyburn reservoir."

When the Kerrs and Ecojustice presented this information to the government and Cenovus nearly four months ago, they got a lot of silence.

That's why they released the report yesterday. "We want to bring attention to this so our neighbours can protect themselves," says Jane Kerr, a retired 57-year-old nurse. The couple also wants a full public investigation and is planning a lawsuit.

'Government's failure to regulate'

"It's a really story about a government's failure to regulate," adds Barry Robinson, a staff lawyer with Ecojustice. "A farm couple shouldn't have to hire a private contractor to get a proper study done. The government appears to be in denial about its golden goose."

Now Rhona Deflrari, a spokesperson for Cenvous, say the Kerrs are well known to the company and that the oil company has hired three experts to pour over the LaFleur report.

However she emphatically adds that, "There is no evidence that any activity of Cenovus has done any harm of any kind to the Kerr's property."

The Petroleum Technology Research Centre says the same thing. It promises that "a response to this report will be provided once it has been thoroughly reviewed."

Where is the data?

But the PTRC statement doesn't explain why public monitoring data on a so-called world class demonstration project appears to have disappeared since 2004.

Nor does it explain why the research group hasn't done field studies on the integrity of abandoned wells in the Weyburn field as claimed by Ecojustice.

The Kerrs aren't the only folks asking tough questions about carbon storage these days. In recent months scientists have raised serious concerns about the efficacy of burying massive amounts of carbon underground.

At Duke University, for example, researchers reported that CO2 leakage would not only acidify groundwater but mobilize heavy metals such as iron and zinc and thereby contaminate local aquifers. (Tests on water from the Kerr property have found high levels of acidity and heavy metals too.)

Last month the Stanford University geophysicist Mark Zoback challenged the viability of large-scale carbon cemeteries altogether. He concluded that the injection of vast volumes of CO2 underground could trigger small earthquakes that could in turn create fractures like those in the Weyburn field.

"While the seismic waves from such earthquakes might not directly threaten the public, small earthquakes at depth could threaten the integrity of CO2 repositories expected to store CO2 for periods of hundreds to thousands of years," stated Zoback.

Reduce or sequester?

Last but not least a Danish researcher reviewed the potential for leakage and concluded that the "dangers of carbon sequestration are real and the development of this technique should not be used as an argument for continued high fossil fuel emissions. On the contrary, we should greatly limit CO2 emissions in our time to reduce the need for massive carbon sequestration."

Cameron Kerr, a plain-talking farmer, hasn't read all these studies. But he does have one word of advice for Alberta which plans to bury millions of tonnes of CO2 under farmland throughout the province at a cost of $1 billion to $2 billion a year.

"Don't let it happen. Shut it down now. You'll have no different response from government than we got. And you'll waste lots of taxpayers' money." ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: