Our country prides itself on its ethnic diversity. This goes hand-in-hand with a general openness to immigrants who bring the many wonders that their respective cultures have to offer, from all corners of the globe.

More often then not, our cities are the first stop for immigrant populations looking to come into Canada. This is no surprise since urban environments offer the wide range of services, amenities, and employment opportunities necessary to ease the transition into an unfamiliar cultural environment.

Over the past few decades, Vancouver has grown as a significant landing pad for incoming immigrant populations and although the locations where incoming immigrants have chosen to start their lives in the city are somewhat known, they are really only discussed in general terms and often in reference to "cultural pockets" that have matured enough to be readily visible.

Enshrouded by this blanket of generality, the underlying forces that shape the decisions of immigrant populations looking to call Vancouver home often go unnoticed.

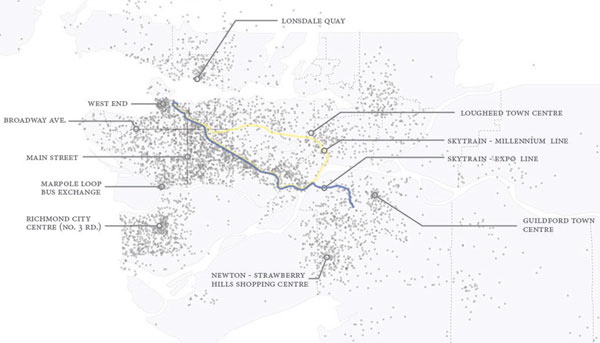

This drove the development of the map you can see by clicking here that charts the locations of incoming immigrant populations to Metro Vancouver from 1981 through to 2006. To be more specific, this graphic compiles the spatial distribution of incoming immigrants by census tract for the years of 1981, 1991, 2001, and 2006.

I chose to combine all of the information into one graphic as a means of highlighting larger patterns that are less visible when looking at each year individually. This occurs as the cumulative effect of overlapping dots form dense clusters across the metropolitan landscape.

I've taken the liberty of labeling the locations of the most significant clusters and reference the main infrastructural elements (i.e. Broadway, the Skytrain lines, transit nodes, etc.) that seem to play a part in the locations chosen by immigrant populations.

Although clusters are distributed throughout the region, the tie that binds these dense nodes is access to transit. The largest clustering occurs as a diagonal swath across the region alongside the Expo Line from Vancouver through to New Westminster. Less so along the Millennium Line given that it was only recently completed (in 2002) at the time of the census. The Canada Line, of course, wasn't built yet so is not included in the graphic.

Travel goes both ways

Consequently, those who decided not to live near Skytrain lines, found locations that were close to regional transit nodes, such as Guildford Town Centre, Richmond City Centre, or Lonsdale, that allow for easy access to transit.

With this in mind, it is no surprise that Metro Vancouver's transit nodes are the cradles of our regional cultural diversity. Both are intertwined in a symbiotic, mutually supportive relationship whereby immigrants move near transit nodes that allow them to travel around the city; over time, as more immigrants move to these areas, they begin to establish themselves as a neighbourhood with entrepreneurs opening culturally-specific businesses nearby.

This, in turn, attracts "outsiders" interested in experiencing and partaking in the unique culture (events, food, etc.) available in the area and who can exercise the use of transit.

The reason for this pattern is straightforward, being the directly result of the needs of incoming immigrants who require accessible transit as a means of navigating the city in the absence of cars and drivers licenses. Only once they get more established -- financially and otherwise -- can they move to break their dependence on transit.

Affordable housing is key

Also related to the need for transit is the necessity for a variety of housing options around transit nodes. This is to say that house types that can support the needs of immigrant populations (i.e. with extended families, etc.) -- that can be rented or bought affordably -- are a prerequisite for incoming immigrant households.

Understanding this pattern is particularly relevant now, as increasing pressures to develop and densify transit nodes are radically altering existing neighbourhoods around Metro Vancouver. All too frequently, this means the construction of expensive condominiums catering primarily to two person households -- building types that offer developers the highest return on investment. Yet, as the graphic clearly demonstrates, among many of the benefits that a good transit system brings, one of the most important is supporting the immigrant populations that bring so much vibrancy, life and diversity to the region.

So as we exercise our powers of creative destruction and continue to reshape our cities around transit hubs, we must ensure to meet the needs of this transitioning population explicitly in terms of diverse housing and transportation options. A failure to do this literally puts the social health and energy of the region at risk.

[Editor's note: For a related article, with animated map, by the author looking at the spatial distribution of incoming immigrant population information between 1981 and 2006, and viewing the data in sequence over time, go here. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: