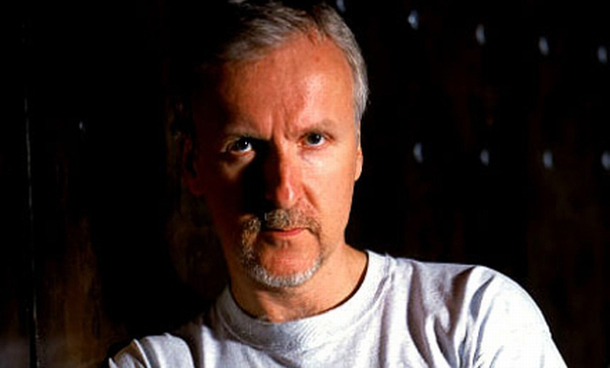

James Cameron, one of the world's most famous story tellers, is the sort of Black Swan that multinational oil companies and Alberta politicians never imagined would land anywhere near their huge toxic tailing ponds in Canada's oil sands. Although imperfectly prepared for ducks and geese, neither big oil nor Canada's Saudi princes had any idea how to deter let alone welcome a big Hollywood bird.

Yet after three days of sponging up the energy-intensive nature of bitumen and the corrosive politics of oil sands development, Cameron, the Canadian-born son of an electrical engineer and a physics major, managed to say what no Canadian politician has had the courage to declare about the mega project: "It will be a curse if not managed properly or it could be a great gift if managed properly... Right now it's going in the wrong direction... I think the federal and provincial government need to play a stronger role."

Now Black Swans are simply small and unpredictable events that can create big ripples in a complex globalized economy.

Nicholas Nassim Taleb, the Levantine philosopher who coined the expression, argues that rare shocks and jumps pretty much shape every aspect of our social and political lives and that we all now live in Extremistan. The economic critic also thinks that ordinary folks behave like shipbuilders who don't believe in icebergs. He'd probably argue that Alberta politicians possess even less insight.

What a Black Swan can do

In recent months Black Swans have improbably shaken up the fossil fuel business. Although degreed experts confidently pronounce all petroleum activity as stable and secure in Extremistan, shit still seems to happen. The BP blow-out pretty much rearranged life in the Gulf of Mexico as well as all the regulations for deep water drilling.

On land, the rupture of two Enbridge pipelines ferrying bitumen across Michigan and Illinois also sent deep shockwaves through the petroleum industry. These modest Black Swans (two leaks) polluted a river, shut off more than 500,000 barrels of crude a day, upset the operations of five refineries in the Midwest, boosted the price of oil for millions of consumers, forced companies to barge gasoline up the Mississippi River and lowered the price of bitumen. The leaks also threatened the future of a 1,000 kilometre-long proposed pipeline from Alberta to the port of Kitimat, B.C. to put more cars on the road in China.

In other words, Black Swans tend to illustrate the brittleness of over-engineered systems the same way a child can effortlessly deflate a pompous adult.

And so when James Cameron, the eloquent director of Aliens, Terminator and Titantic, accepted an invitation from Canadian aboriginals to visit the world's largest energy project, Alberta's corporate czars held their breath. Many sweated like boiler room engineers on the Titantic.

Premier Ed Stelmach, a bumbling bitumen servant who has yet to visit the embattled downstream community of Fort Chipewayan, even rearranged his schedule and commandeered a private jet to catch an audience with the icon.

Trying to shoot him out of the sky

Meanwhile spin doctors in the corridors of petro power questioned Cameron's motives the same way Saudis view foreign visitors. Some swore that the film director was a hypocrite to fly into the region, because as any Albertan knows you can't criticize fossil fuels and use them at the same time. Others hinted that only pinko Liberals and New Democrats watched Cameron's films anyway. Others dismissed the Canadian as a dangerous interloper.

(Note to readers: You have to live in Alberta to appreciate the subtle nuances of a dysfunctional state ruled by one political party for nearly 40 years. Even the U.S. Council On Foreign Relations describes this Texas-like petro kingdom as "skeptical of environmental management.")

Less oily folk speculated about the impact of Cameron's visit, too. Could a film director as famous for exposing human hubris as well as living it say something that might unravel a $200 billion project? Would the technical wizard behind the globe's most popular film, Avatar, compare the mined-out landscapes north of Fort McMurray to the blighted developments portrayed in the cinematic 3-D world of Pandora?

Cameron's science nerd tour

Petro states, of course, are much more sensitive to criticism than normal democracies. Being fragile objects subject to the extreme volatility of oil prices and the ire of oil patch lobbyists, petro politicians fear the pronouncements of Hollywood as much as they scorn the antics of Greenpeace.

When Cameron initially described the bitumen mining development as a "black eye" on Canada's environmental reputation several months ago, members of the Alberta government and the Edmonton Sun suffered the sort of paroxysms hapless space travellers do when incubating aliens get ready to pop from their chests. Even before Cameron frankly pronounced his views, Premier Stelmach, sounding more and more like a grumpy Venezuelan dictator, warned that shadowy "sinister forces" had a hidden agenda against Alberta and the oil sands.

Unlike Stelmach, Cameron did the right thing before opening his mouth. He donned a Syncrude hat and rubber boots and visited a small reclaimed mining site. After listening to their corporate story, he poked around a Suncor tailings pond whose waste had been transported to another pond to create good industry PR. Then he examined the primitive and energy-wasteful technology used to steam bitumen out of the ground. The man asked lots and lots of questions. Even the right-wing National Post commented that Cameron behaved more like a science nerd than a crusader.

In the community of Fort Chip, a place as big as Cameron's home town of Kapuskasing, the director patiently listened to the concerns of aboriginal fishermen, hunters and oil sand workers. (Many asked why the Alberta government didn't behave this way.) A 2009 Alberta Cancer Board study found a 30 per cent higher rate of cancer in the community than expected. Peer reviewed science has now documented cancer makers and heavy metals in waters downstream of the mining and refining project.

Next, Cameron sat down with Premier Ed Stelmach. They had a "gracious and polite" discussion as one farmer's son does with another farmer's son. But they didn't agree about much.

'The world is looking at what you do'

And then the Black Swan landed at one of the biggest press conferences witnessed in Edmonton in a long time. Accompanied by Shawn Atleo, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations; Gerald Amos of Kitimat's Haisla First Nation, George Poitras, former chief of the Mikisew Cree First Nation and Chief Al Lameman of the Beaver Lake Cree, Cameron spoke with the kind of honesty and brilliance citizens pray they might someday find in their elected representatives.

The chiefs didn't mince words, either. Atleo called Cameron's visit "a historic moment where art imitates life," and demanded that Canadians respect treaty rights in the region. Amos said the proposed Enbridge pipeline to transport bitumen from Alberta to Kitimat would threaten the sustainability of B.C. coastal life. "The issue for First Nations is the pace and scale and type of development that is allowed to happen on our territory."

Cameron didn't miss a beat or utter a cliche. Without notes or script he simply spoke as a citizen of the world who brought a pair of fresh eyes on the project which proved to be as "bad or worse as I thought it was." Yet he called bitumen "an incredible resource and I understand why everyone has stampeded toward it." But he defined it as a transitional source of power. He deplored the influence of the oil patch on U.S. energy policy, which was moving from "being brain dead to slowly coming out of a coma."

Cameron also strongly advised both Alberta and the federal government, who have yet to do a cumulative impact study on the project, to get a handle on the full environmental and economic costs and to "future proof" the monster development.

Cameron, a man who understands complexity, didn't call for an end of the oil sands but for significant reforms. Given the difficulty and cost of reclamation (industry has spent 10 times the amount of money on PR plots than it has budgeted for all the disturbed areas), he recommended a moratorium on any more tailing ponds. He also called for better monitoring on the Athabasca River. He said that industry-funded science made a "good prop" but nothing more. He demanded more independent peer-reviewed science, something neither the Alberta government nor its industry funded monitoring group has ever produced. The techno-geek and inventor also accused industry of using obsolete technology. "The world is looking at what you do here."

Skeptical of 'immaculate conception'

He also didn't buy the big denials about industry contamination of the river with heavy metals and hydrocarbons. (Incredibly both industry and government claim all pollution in the river comes from naturally eroding bitumen deposits.) "It's hard to imagine a refining and mining process of this scale that doesn't have an impact. That would be some kind of immaculate conception."

Cameron also recognized that the mining projects, despite their "horrific" city-sized scale, remained the most economic and energy efficient. In contrast he called the steam plants, the future of the oil sands, a much dirtier and carbon intensive process in which "you are using as much energy as you get out."

In the end, Cameron, the father of five children, called for what both Alberta and Canada have tried to avoid: informed debate about unconventional energy and its full long-term costs. He demanded better science, better regulation and a dramatic slowdown until key issues had been resolved. Most of all he called for respect for aboriginal rights and health downstream. He sounded a lot like a younger Peter Lougheed.

Cameron also mentioned climate change and warned it could be a powerful determinant of the project's size and future. When it comes to understanding what's happening to this planet, "we are all indigenous people now," added Cameron. "We're all connected."

After this unscripted spontaneity and honesty, Alberta's politicians didn't know what to say afterwards. At a legislative press conference much larger than the one held after Stelmach's election, the premier stood alongside three blue-suited cabinet ministers. All four men looked like four deer caught in a Hollywood spotlight.

After mumbling something about whether one liked Cameron's visit or not, Stelmach read from his usual Saudi-like script: "We're doing our part to move the world to a cleaner energy future." He also announced a community health study for Fort Chip and then left the room like a man oblivious to swans.

A vow to return

Cameron, however, not only promised to return but made a "life-long commitment" to reforming the project and advocating for aboriginal rights. Perhaps the only thing worse than a Black Swan is a returning one.

In the end, I asked well-informed Paul McLoughlin, the publisher of Alberta Political Scan and an observer of the province's petro politics since 1983, just what kind of impact the Hollywood bird would have on Alberta.

McLoughlin was pointed and terse. "I think it's good that Cameron is using his celebrity to improve aboriginal rights and to pull the Alberta government and corporations in the direction of environmental stewardship. They are still going to produce the hydrocarbons. But the environmental damage will be less because of this exercise."

Outside of Alberta the Hollywood swan just may generate bigger waves on bigger ponds in unpredictable ways. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: