On the afternoon of June 30, when parts of B.C. were engulfed in flames, Julia Kidder was alone in a friend’s SUV, barrelling down a road she could barely recognize.

That was bad. Kidder had driven the highway between Kamloops and Cache Creek many times. But as temperatures outside reached 47 C, the drive to her house in Ashcroft, B.C. became stranger and stranger.

Kidder’s vehicle had broken down a few days earlier. She had gone to Kamloops to borrow a friend’s car so she could be ready to flee with valuables, including her mother’s ashes, if wildfires neared Ashcroft.

The SUV had no air conditioning and Kidder, a communications specialist at the non-profit West Coast Environmental Law, kept spritzing her face and neck with a spray bottle. Yet she felt severely dehydrated. When she saw a wildfire vaporizing trees on a nearby ridge, she was still able to call the wildfire service.

But as the 36-year-old kept driving, the text on the highway signs seemed to be melting and falling. She started hearing laughter in the car and thought someone was on the phone. But when she picked it up, there was no one. Instead, the phone was flashing a warning it was too hot.

Finally, she called her father, accompanying her in another car and five minutes away. Worried, he asked her to pull over at the next rest stop.

She doesn’t remember him saying that and thought she was still hallucinating. On the verge of fainting, Kidder suddenly had a surge of energy, pulled off the road, opened the car door and passed out.

Growing crisis, slow response

The late June “heat dome,” which trapped hot air over much of the province, killed 570 people in B.C.

And two environmental organizations say extreme heat waves affect the health of many more people, causing brain injuries and other damage due to heat strokes and severe dehydration.

The province needs to begin tracking the impact, say the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment and West Coast Environmental Law.

The organizations estimate between 5,000 and 6,000 British Columbians suffered heat-related injuries in the first week of the heat wave. That’s based on a 2019 risk assessment by the provincial government which predicted that for every 100 deaths caused by heat waves that last for more than three days, 1,000 people would be harmed.

But estimates aren’t good enough, the groups say, and the province should be gathering better data on the impact of heat waves as they become more frequent due to climate change.

This could be as simple as assigning a billing and diagnostic code that doctors could use to record any health conditions caused by heat waves, in the same way they tracked COVID-19. But no code exists for heat-related illnesses.

Dr. Melissa Lem, the incoming president of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, said in the statement the heat wave had been devastating.

“For every person who died from the heat dome, 10 or more may have suffered heat stroke, dehydration or other complications, including permanent, life-altering injuries,” she said. “I saw more patients with heat illness during June’s extreme heat than I have in my entire career. Physicians need direction from the province on how to track these injuries.”

The two groups believe that measuring the health impacts of heat waves would help in holding government accountable and developing an effective response.

So far, the government has done a “poor job” of responding to the heat dome, says Andrew Gage, a lawyer at West Coast Environmental Law. “I think that’s pretty clear.”

The government’s 2019 risk assessment warned that extreme heat waves were going to be more common in the future, coming once every three to five years by 2050.

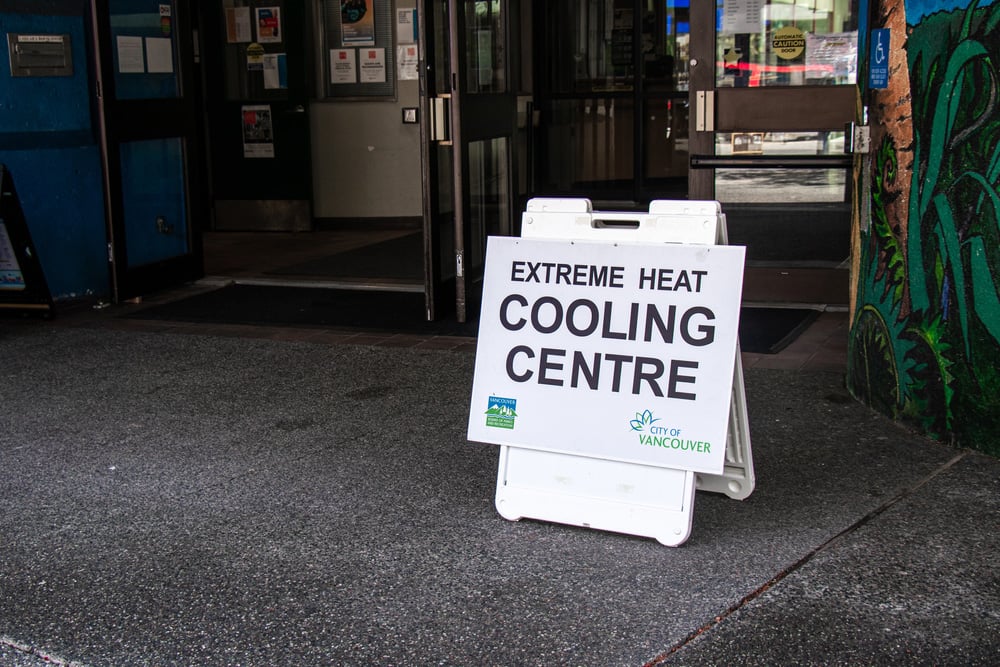

But the June heat dome showed basic measures, like access to water and cooling stations, were inadequate.

Gage said the province hasn’t created a comprehensive strategy to counter such calamities.

The Health Ministry told the Canadian Press the province “is developing a plan to prepare and adapt to climate change.”

“The province is also working to better understand climate change impacts and published a provincial climate risk assessment that is informing the development of climate preparedness and adaptation strategy,” it said in a statement.

Gage said the response is hollow.

In its current Climate Preparedness and Adaptation Strategy, the only specific action in the next five years to tackle heat waves is to “support BC Housing to lead the development of a provincial extreme heat and wildfire smoke response plan for populations disproportionately impacted by climate change.”

In 2018, then auditor general Carol Bellringer produced a damning report that found the government hadn’t updated its climate adaptation strategy since 2010.

The report called for clear timelines, roles and responsibilities and consideration of social and economic costs, none of which were featured in the province’s recent strategy to address heat-related calamities.

“It seems like this government does understand that climate change is serious and urgent, but it doesn’t look like it… these issues impact people in real-time,” Gage said.

Dr. Larry Barzelai, B.C. president of the Canadian Association of Physicians, told The Tyee that heat waves harm vulnerable groups such as the elderly and the homeless the most.

“It’s a real dividing line in terms of socioeconomic status. For instance, people higher on the socioeconomic [ladder] have air conditioners and better ventilation, whereas others live in apartments that are smaller and heat up faster and have poor ventilation.”

Research shows that long-term damage from heat strokes is rare. But symptoms such as headaches could last up to four months and harm workers who can’t afford to take time off work.

“It’s really important to calculate the impact of the heat waves on our vulnerable populations,” Barzelai said.

A slow recovery

Kidder came to as ambulances and emergency crews zoomed past her through a thick haze of smoke, sirens screaming. When she opened her eyes, she saw a man in a stopped car next to her, clapping and shouting.

“Hey! Are you OK? Do you know where you are going? Do you need a gas mask?”

Kidder replied that she was heading to Ashcroft.

“You can’t take the road to Vancouver,” he told her. “Lytton just burned down.”

Kidder thanked the man and told him that her father was on his way.

She wasn’t aware that she was having a severe heat stroke; she felt she was being "dreamy.” When her father arrived, they switched cars so she would have an air conditioner.

When she reached home, her father suggested a cold bath. But she balked — something that she regrets.

“I didn’t know that that’s what you’re supposed to do. That’s how serious it was. I should have just gone into the cold water… I could have probably avoided the serious side effects of this heat stroke had I known how to cool myself down.”

Kidder’s condition worsened, and she started having severe headaches and a high fever. She suffered a loss of balance and felt as if she were walking on a slant.

Her cousin Sara Kendall, a paramedic, picked her up that evening and drove her to the emergency room at UBC Hospital, where she was diagnosed with heat stroke.

Kidder, who is set to begin her PhD research in coastal adaptation and Indigenous governance at the University of British Columbia this fall, says she has been concerned about climate change since childhood.

But now the threat seems real, and personal.

“I had to stop obsessively looking at the wildfire map. But I couldn’t, because the fires kept encroaching [on] where we live,” Kidder said. “This is definitely human-caused climate change because heat of this severity is not possible without it, and that is because of the burning of fossil fuels… I could have easily lost my life.”

Kidder was relieved when the UBC doctor told her that she didn’t have permanent brain damage. However, her recovery took more than three weeks.

“There was this continued feeling of disorientation that’s really hard to describe, that just feels like you’re in a fog. And then there was numbness in my hands. The recovery process was just me taking rest and trying to be as quiet as possible. I was talking in my sleep; I was feeling very emotionally overwhelmed.... Other than my mom dying, this has been the most formative, intense experience in my whole life.”

She said she was fortunate to have someone to take care of her. But many people wouldn’t have that support, she noted. “I’m white, I’m privileged. I live on land that was purchased by my grandparents which was stolen [from Indigenous peoples],” she said. “I can only imagine how this might have affected a more vulnerable person.”

She still thinks about what would have happened if she had passed out while driving. “I could have easily driven off the road or, you know, hit somebody else or something awful,” she said.

“I feel lucky to be alive.” ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: