The family of a man killed in a police altercation last week says that RCMP and media attention focused on the death of a police service dog in the same incident is perpetuating racism and undermining the loss of a man they describe as a gentle giant.

Jared Lowndes, who is from the Laksilyu Clan of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, was shot multiple times after he was cornered by RCMP officers at a Tim Hortons parking lot in Campbell River on July 8.

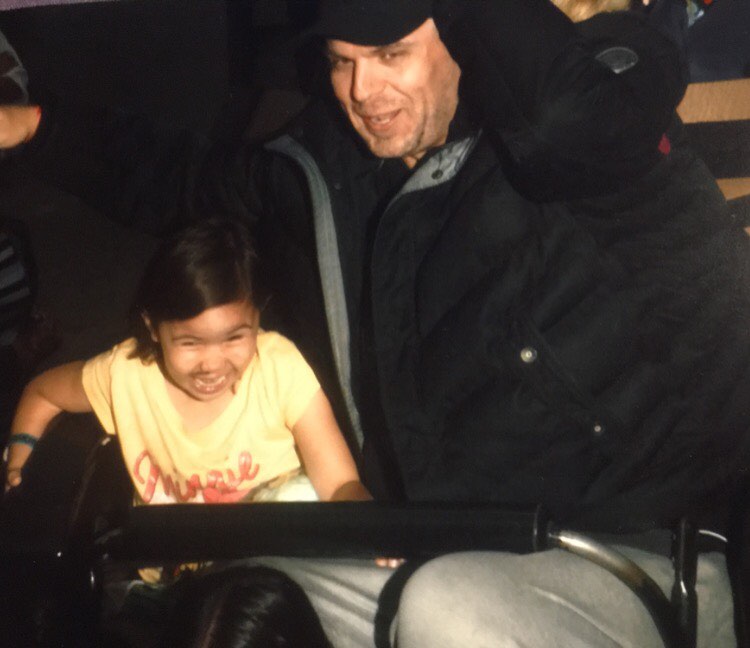

His aunt, Fay Blaney, says the tall father of two was “well loved by everybody,” and had a special fondness for children and pets. Lowndes’s four-month-old puppy was in the vehicle with him, and she believes he may have been defending his own dog when he stabbed a police service dog that the RCMP sent into his car.

But she says that media attention and ceremonies held for the police dog have made the family a target for racist comments and made grieving her nephew more difficult.

“This is a human being, a life that was lost, and he was loved,” Blaney said. “He was important. It was a lot of work to even bring any attention to this.”

An RCMP statement released the day of Lowndes’s death says that Campbell River RCMP attempted to stop a vehicle in relation to an outstanding warrant. After the vehicle failed to stop, police “boxed in” the vehicle at a nearby parking lot and a confrontation occurred.

“During the interaction, the police service dog was stabbed and killed, and the suspect was shot and was pronounced deceased on scene,” the statement reads. The police dog handler was treated for a knife wound, it added. B.C.’s Independent Investigations Office is investigating the shooting.

Hours later, RCMP issued a second statement, this one dedicated to Gator, the police service dog killed in the incident.

“It is with great sadness that we share that earlier today our Police Service Dog Gator died while assisting with a call in Campbell River,” this statement read, adding that no further information would be released as the incident was being investigated by the IIO.

Media outlets quickly jumped on Gator’s story. The day after the shooting, Campbell River Mirror coverage of the shooting led with the death of the police service dog, giving passing mention to “the death of a male” in addition to the dog.

The article was syndicated in Black Press newspapers across the province.

Other outlets followed.

“Memorial grows for Gator, police dog killed in Campbell River incident,” reported Chek News on July 10. “Procession for Gator along Dogwood St. today,” read the headline in My Campbell River Now the following day.

On July 12, Black Press followed its initial coverage with a story about hundreds turning out for a parade honouring Gator that was hosted by Campbell River RCMP.

Blaney called the reporting “lazy” and added that it does little to honour the life of Lowndes.

Speaking for both herself and Lowndes’s mother, Laura Holland, Blaney said that the media’s focus on the police service dog has glorified the dog while villainizing and undermining Lowndes’s life.

People have vandalized the memorial set up for Lowndes and sent racist comments to the family over social media.

“This is a way to detract from their own wrongdoing,” Blaney said, referring to the RCMP.

Blaney said Lowndes was injured, had no means of communication and was boxed in by police when the service dog came at the passenger side of his vehicle. He likely felt trapped, she said.

“This just goes to show the degree of helplessness that he may have felt in his final moments,” she said.

Lowndes himself had expressed feelings of helplessness and fear of police in an essay written just days before his death.

In the essay, which was distributed by family at his memorial, he spoke about his family history in northern B.C. and how his mother was hidden from Indian agents and the RCMP who sought to remove her from her family in the 1970s.

Shortly after he was born, Lowndes said his mother fled the area for Vancouver, where police and social workers placed him in foster care at age four.

“I was taken from my mother at gunpoint and brought across the city to a foster home,” Lowndes wrote, adding that while in care he was mentally, physically and sexually abused. He said he was charged with assault twice after defending himself from abuse in both a group home and a foster home.

After being released, he was told the system could not help him and he was left to fend for himself from age 13.

“I spent the next 16 years drinking, doing drugs and wasting my life away, because I thought I wasn’t worth it,” Lowndes wrote. “I’m now in my late 30s and my daughter, dog and I are homeless, living out of my car. All because I can’t trust.”

The essay said Lowndes had been sober eight years.

On Tuesday, the First Nations Leadership Council, made up of the BC Assembly of First Nations, First Nations Summit and Union of BC Indian Chiefs, expressed outrage at the “dehumanizing treatment” of Lowndes by Campbell River RCMP.

“The incident, which saw no attempt at de-escalation from the RCMP, left the 38-year-old father dead, his family seeking answers, and a community divided, as racist, hateful sentiments begin to rise,” it said, pointing to colonial violence, discrimination and disenfranchisement as having left Lowndes distrustful of police.

“When the RCMP attempted to stop him on an outstanding warrant, boxing him in at a Tim Hortons and sending in a police service dog, his experiences as an Indigenous man likely left him fearful, re-traumatized, and acting in self-defence,” it said.

“The police put Jared into an unnecessary, preventable situation that forced him to act under extreme duress and fear.”

The dehumanizing treatment continued after Lowndes’s death, by both police and media, the statement said.

“He deserves to have his name spoken out loud and his life remembered — that a dog would receive more news coverage and be prioritized over his life is unspeakable and unconscionable,” UBCIC’s Grand Chief Stewart Phillip said.

In an email, RCMP Staff Sgt. Janelle Shoihet said that because police are restricted by what details they can disclose when an incident is under investigation by the IIO, the information released about Lowndes mirrors other similar incidents.

She added that police service dogs — and their deaths in the line of service — are treated like RCMP officers.

“When a serving dog dies in the line of duty, the impact is felt not only by their handler, but that detachment, the greater RCMP family and the members of the communities he/she serves,” Shoihet said. She added that when an officer dies, how the force responds is done in consultation with the officer’s family.

“On the same token, the impacted detachment may choose to mourn and recognize the dog’s death in whatever way they feel is most appropriate after careful consultation with the handler, who is the police dog’s family.”

Gator was the second police service dog killed on the job in less than a month, she said.

In June, Lionel Ernest Gray, an Indigenous man from northern Alberta, and police service dog Jago, originally stationed out of the Lower Mainland, were both killed when Gray exchanged gunfire with RCMP officers after a manhunt near High Prairie.

The incident was referred to the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team for investigation. RCMP held a procession and lowered their flags to half-mast for the police service dog after this incident, too.

Three days later, police shot and killed a man near Cold Lake, Alberta after he stabbed a police service dog. The dog survived and ASIRT is investigating, according to media reports.

According to the CBC’s Deadly Force database, Black and Indigenous people are over-represented among police-related fatalities in Canada and incidents appear to be increasing, with as many people killed in the first half of 2020 as the full-year average for the previous 10 years.

Based on the most recent data released in July 2020, Indigenous people form 16 per cent of police-related deaths but only 4.21 per cent of the population; Black people form 8.63 per cent of deaths and 2.92 per cent of the population.

While the data the CBC gathered does not include specific information about incidents involving racialized people and police dogs, a 2020 Ontario Human Rights Commission report into racial profiling and racial discrimination of Black people by the Toronto Police Service found that while Black people made up only nine per cent of Toronto’s population, they were over-represented in almost all use-of-force categories, such as firearms, pepper spray and tasers.

Black Torontonians represented 57 per cent of cases involving police dogs.

The use of police dogs in incidents involving African Americans is something that has been fairly widely written about; the same is not yet true in Canada.

Lowndes’s family is calling for police to be disarmed and to be required to wear body cameras so that officers can be held accountable when their actions lead to injury and death, rather than de-escalation.

The family said that the warrant was a result of a years-old court order for Lowndes’s DNA. But Lowndes had been acquitted of the charges and they felt he should not have to provide that information.

“He was alone,” Blaney said, “and they opened fire on him.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: