New radar satellite imagery shows that intense oil and gas activity has destabilized the geology of a 10,000-sq.-kilometre area in west Texas causing the ground to heave and sink dramatically.

“If we do not mitigate the possible geohazards with continuous monitoring of surface deformation,” warned researchers, “we can expect one or more possible outcomes” including damage to roads, railroads and dams, groundwater pollution, more earthquake activity and “potential threat to residents in surrounding communities.”

Geophysicists at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas, took a hard look at the Permian Basin where companies such as Calgary-based Encana are now furiously fracking for light oil.

The Permian is one of the continent’s oldest oil fields, with more than 30 billion barrels of oil pulled out of the ground over the last 100 years.

The brute force technology of hydraulic fracturing, which injects pressurized fluids to crack open source rock, has reanimated the basin.

But the scientists found that all that activity had taken a toll and resulted in substantial ground movement.

Satellite images, for example, showed that injection well sites which pump lakes of saline water into 3,000-metre-deep oil formations have raised the ground by as much as three to five centimetres in some parts of the Permian.

Satellite radar technology allows scientists to detect ground movement not visible to the eye by sending pulses of energy from a satellite to the Earth. The difference in time that it takes a wave to travel back to the satellite can provide detailed information about movement in ground levels.

The study also found that the ground was sinking near horizontal wells that had undergone hydraulic fracturing near Pecos, Texas, since 2015.

Six small earthquakes had been recorded in the area, “suggesting the deformation of the ground generated accumulated stress and caused existing faults to slip,” the researchers noted.

With the advent of hydraulic fracturing, west Texas has experienced “unprecedented increases” in seismic activity in the last five to six years, as have Alberta and B.C.

The study, published in Nature, also reported that the ground was sinking by two to 10 centimetres around active, abandoned and orphaned wells.

“This region of Texas has been punctured like a pin cushion with oil wells and injection wells since the 1940s, and our findings associate that activity with ground movement,” explained Jin-Woo Kim, a research scientist at the Roy M. Huffington Department of Earth Sciences at SMU.

Researchers also found that in some areas oil and gas activity had created sinkholes by introducing freshwater to salt formations which caused them to dissolve.

Similar issues have plagued oilsands development near Fort McMurray where the melting of salt formations under bitumen deposits has created sinkholes and other geohazards and cracked the cap rock.

“Developing a karst terrain for oil production or other human activities requires careful operations,” said Kim. Karst terrains are based on water-soluble rocks like limestone.

“Improper borehole management (wellbore plugging and sealing, casing, cementing... ) or mistakes in controlling freshwater (aquifer system, rainfall, surface water flow) can lead to the dissolution of evaporite (salt) and carbonate (limestone) rocks. Companies or regulators in oilsand production industry will need to pay special attention to monitoring of surface/subsurface motions for safe operations,” added Kim in an email.

Ground heaving can be so significant in some bitumen regions that industry monitors both pipelines and processing facilities, particularly near Cyclic Steam Stimulation operations. The companies inject steam under the ground for weeks or months to heat the oil, and the surface can be lifted by more than 50 centimetres. The monitoring is important, say researchers, “to protect surface assets that may be subject to harm from ground motion.”

In response to a Tyee query about the Texas study’s relevance to highly drilled western Canadian basin, Kim noted that the ground above every oil and gas basin responds differently to industry activity. It would be difficult to gauge the impact in Alberta or B.C. without a satellite image analysis.

“Even wells with massive oil production and fluid injection can undergo no significant deformation,” said Kim. “But wells with a relatively small fluid injection can experience surface uplift.”

In recent years hydraulic fracturing, in which water, chemicals and sand are injected into the ground under high pressure, has dramatically increased seismic activity in northeastern B.C. and northwestern Alberta.

Several magnitude 4 earthquakes triggered by industry have rocked both areas and raised concerns about groundwater contamination, gas migration, public safety and threats to infrastructure, such as nearby dams.

Anthony Ingraffea, an expert on the science of fractures at Cornell University, said the Nature study clearly laid out the physical consequences of high density oil and gas extraction over time.

“For those who still think large-scale, long-term oil/gas development has no surface manifestations, the study tells them to wake up and see the motions.”

Given the rate of drilling and fracking in places like Pennsylvania, British Columbia and Alberta, “forewarned should be forearmed,” added Ingraffea.

“What is happening in the Permian can happen in those places as we drill our way towards 1,000,000 more wells as forecast by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Cracking sidewalks and basement walls will be the least of our problems.”

In Texas the oil industry has suggested that 110,000 more wells might be needed to drain the Permian basin alone over the next decade.

In many respects the study highlights geohazards that were well known to oil and gas industry insiders but little discussed by the public or regulators.

Around the world groundwater exploitation, waste water injection, freshwater impoundment, hydraulic fracturing, CO2 injection and sustained hydrocarbon extraction have destabilized the ground, leading to heaving, sinking, fault reactivation, swarms of earthquakes and the formation of sinkholes.

Alberta, California, Texas, Louisiana, Venezuela, the Netherlands, the North Sea, Italy, Russia, Georgia and Oman, for example, have all recorded major ground sinking or “subsidence” due to unrelenting oil and gas extraction.

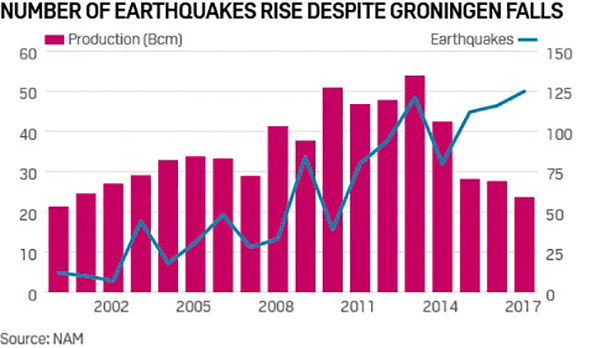

In recent years public concerns about safety in the Netherlands forced a joint venture operated by Shell and ExxonMobil to reduce the volume of methane being pulled from Europe’s largest gas field around Groningen due to swarms of earthquakes.

Residents say seismic activity that they compare to “bombs” as well as steady subsidence has reduced the value of their homes by $1.6 billion.

To prevent further ground sinking and unpredictable seismic activity, the government has ordered industry to cut methane extraction by nearly half since 2013 and is expected to order further reductions.

But the reductions have not stopped the earthquakes. In some parts of Groningen the ground has sunk nearly 24 centimetres due to the withdrawal of methane.

Approximately seven million households in the Netherlands and many large factories still depend on the high quality methane extracted near Groningen.

New research has shown that earthquakes have been a regular but hidden companion of the oil and gas industry in Texas since 1925. Fluid injection caused some of the earthquakes while others were triggered by the shear volume of hydrocarbons extracted from the ground.

A 2016 study found that most seismic activity in the state was often “situated within a few kilometres of high-rate injection wells or near fields where large volumes of oil and gas have been produced over many years from relatively shallow strata.”

In contrast to what the science now says, Texas regulators have been reluctant to admit that industry can literally make the ground move in hazardous ways.

In 2015, D. Craig Pearson, an earthquake seismologist employed by the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates the oil and gas industry, even claimed that there was “no substantial proof” that induced earthquakes have occurred in Texas. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: