The nurses in Mississauga Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit had been trying to convince Donna May to take a break for hours. She hadn’t eaten or been outside all day. She’d stayed with Jac, her daughter, who was in the ICU dying of complications related to years of intravenous drug use. Earlier that year, Jac was hospitalized in Surrey when her legs became inflamed as a result of necrotizing fasciitis, a severe infection killing the body’s soft tissues for which intravenous drug users are at increased risk. Her mother had flown across the country from her home in Mississauga to find her in Surrey Memorial Hospital’s Intensive Care Unit. The hospital discharged Jac into her mother’s care, who took her home to Mississauga in late February 2012, where they spent the final months of Jac's life together.

Stepping outside the hospital, the air was warm. May looked at the moon. “I thought it was beautiful,” she says. “I wished Jac could see it too.” It was 10:10 p.m. on August 21, 2012. Inside the hospital, Jac, 34, drew her last breaths.

Jac died in hospital, in a context that did not count her death as part of the illicit drug overdose data kept by provincial coroners.

“The manner of death is undetermined,” wrote Ontario coroner David Lewis in the coroner’s investigation statement for Jac’s death. “It is probable that the deceased died of mixed drug toxicity, intentional or accidental, combined with aspiration pneumonia which occurred due to vomiting due to intubation.”

May had found Jac in her bedroom the night before, moaning and struggling to breathe. She had been taking prescription opioids to manage chronic pain. In the emergency room, her blood test was positive for the opioids morphine and methadone, as well as benzodiazepine and tricyclics, both used to treat anxiety and depression.

The coroner recommended that the Hospital Quality Care committee review its use of naloxone, a drug that reverse the effects of opioid overdoses. It was not used when Jac was in the emergency room. “At the time, she [the emergency room physician] felt that narcotics were not the cause of the deceased’s problems,” wrote Lewis in the coroner’s report.

But Jac’s story, many times over, must be included in the toll taken by opioid addiction and the criminal underground into which it pulls so many because of current laws and policies.

The toll extends beyond users to their friends and family – to loving parents like Donna May who suffer alongside their children, struggling to make meaning of their unfolding nightmares.

‘Something different’

The year Jac died, 2012, was the first year that the powerful opioid fentanyl appeared on coroner’s reports as a contributor to a growing number of overdose deaths in B.C. Though she had lived in the Downtown Eastside and Surrey, Jac wasn’t counted as one of them. And her death did not become part of the Ontario coroner's data for overdose deaths in her home province. However, Jac’s fentanyl use led to health complications that resulted in her death.

Many lives like hers do not exist as part of the coroner’s illicit-drug death data, but are related to drug use. Like many others, Jac was using drugs to cope with a tumultuous life in which volatility and trauma featured strongly.

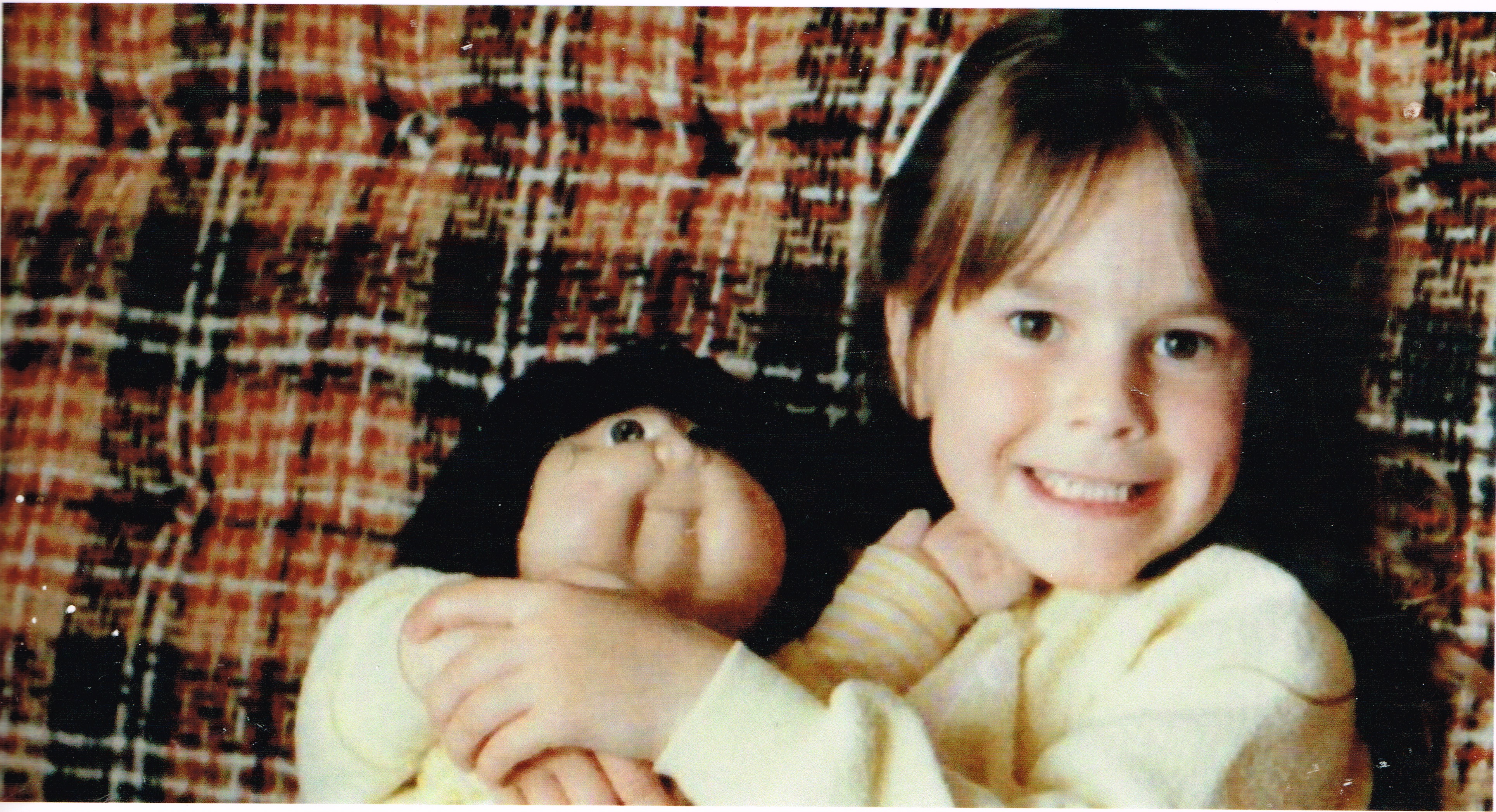

She was a quick, charismatic kid who spent her childhood in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. “She lit up a room, comical beyond belief. She could make something funny instantaneously. And that was the joyful part about being around her,” May remembers. “She was also very brilliant beyond my capacity of knowledge.”

But Jac was bored. She didn’t like school; she wanted more of a challenge. And of most concern to her mother, Jac couldn’t seem to demonstrate or understand much empathy or compassion.

“I knew, at a very early age, that there was something different,” she says. She tried to seek help through psychiatric counselling. “But the responses that I got were, ‘Your daughter’s too young;’ ‘We don’t make these diagnoses.’”

Other counsellors suggested that May change her parenting skills. She was only 20 when Jac, her second of three children, was born.

“I already had this concept in my mind that I don’t parent properly. So when people continued to tell me, ‘You’re the one who’s not parenting your daughter properly,’ I bought that and took that on and thought, okay, well, more discipline. More times out. Showing her more attention,” May says. “I did everything that I could possibly do to work with her to get her to understand the right from the wrong and things like that. But it never changed.”

For years, she tried in vain to take a tough love approach to fix her child, the kind of hard-lined, punitive parenting that seemed common. “I was like, ‘She’s going to straighten out. She’s going to hit rock bottom,’” she recalls. “It never worked.”

May tried to punish Jac for it by taking privileges away. But doing so only drove her daughter away from her and into increasingly dangerous situations.

As soon as she was able, Jac ran away from home, started using alcohol, and smoking marijuana—“the typical things ‘bad’ teenagers do,” as her mother describes it.

But she also got into heavier stuff, like theft and turbulent romances that left her pregnant at 15. She kept that child and two others. She also aborted two pregnancies and put another child up for adoption. She felt conflicted about it all.

It was, her mother says, “an awful lot…just a lot of emotional traumas, constantly. It was always a drama. Always. It never ended.”

Jac was already vulnerable when she started using opiates. After falling hard down a flight of basement stairs in her late twenties, her doctor prescribed her OxyContin, a time-released pain medication for people needing around-the-clock relief.

The drug helped Jac beyond her injuries. She struggled with debilitating social anxiety that could make daily tasks difficult; going out to shop for groceries or taking her kids to school felt impossible sometimes.

The new prescription made things feel more comfortable. “I’m functioning,” Jac told her mother. “And it feels good.”

May, who had watched her daughter struggle mightily, was overjoyed to hear that she was experiencing even a measure of relief. But Jac’s doctor cut her off from her prescription when she disclosed to him that the OxyContin was helping with her social anxiety. According to May, he fired her as a patient.

Jac found workarounds, taking prescriptions from anyone she could find. Eventually, with few options left after various acquaintances cut her off, she turned to the illicit market, where she bought fentanyl patches and started using them to relieve her pain.

“In and around that same time, she got involved with the criminal elements very deeply,” May remembers. “I think she always had a foot in that world. But it was very apparent that that’s how she was surviving.”

‘Beginning of the end’

Jac spent her late twenties and early thirties surviving on petty crimes, sex work, and trafficking and manufacturing drugs. Her mother had moved to the Greater Toronto Area from Sault Ste. Marie after she and her ex-husband divorced when Jac was a child.

One day, she got a call from the Children’s Aid Society saying that her grandchildren had not been attending school. May returned to Sault Ste. Marie to spend a week with Jac and her grandchildren, trying to sort things out and clean her daughter’s apartment, where the children were sleeping on piles of dirty clothes.

“I went out and bought groceries galore,” she says. She filled the cupboards and went out again, intending to make lunches for her grandchildren to take to school when she came back.

But when she returned, everything she’d purchased was gone. Jac didn’t give her a straight answer as to why, so May sat in her car outside the building and watched people come and go throughout the evening.

“That night that I sat there, the apartment just lit up like it was a highway truck stop,” she says. “She had sold the food to get money for drugs.”

That’s when May decided to take her grandchildren out of her daughter’s care. “That was the beginning of the end of Jac’s life.”

As Jac became more involved of the criminal elements of drug addiction, she became an informant to the police. The wrong people found out what she was doing and put a hit out on her life in 2010.

“One of the three people that were hired to kill her had a change of heart, literally as the knife was at her neck,” says May. “He was murdered just a couple of weeks afterwards for not following through with what he was told to do.”

Jac survived the hit, but was still in danger. “She had nowhere to turn,” May says, including to her own mother, who she was angry at for taking her children away. “There’s no trust there.”

So Jac moved west, landing first in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and finally a stretch of 135A Street in Surrey known as “The Strip” for homeless encampments and drug scene.

Her mother tracked her down after filing a missing person’s report. The two were in and out of touch until May got the call from Surrey Memorial Hospital that Jac was in the ICU.

“I can remember flying from Toronto and just going, ‘Live. Just live. Let me say goodbye,’” she says.

“And just being in utter shock. I don’t know how I could be in shock after everything else that had happened. But I think the shock came from realizing that everything I had done had failed. I didn’t have any answers. I didn’t try hard enough. I didn’t do enough—all these self-blame and self-doubting and things like that. I think that by the time I got off the plane, I had decided in my head if I found her alive, I would be by her side ‘til the day that she died. And that would be my only way of forgiving myself.

And I did that.”

May and her daughter began a slow process of making amends. They’d talk late into the night. For the first time, May started to understand the complicated nature of her daughter’s life. “She began using because it did make her feel socially acceptable and able to cope with what was going on,” she says.

Jac also told her mother, “I just know I’m dying.”

She said, “‘I want this time to teach you,’” May recalls. “Meaning addiction, and how she lived her life.”

In the years since Jac’s death, May has tried to carry out her daughter’s final wishes to make meaning out of her life.

‘We have turned them into criminals’

May has worked as an interior designer and a law clerk. Today she pours most of her energy into advocating for a harm reduction approach to drug addiction. In that role, she has spoken before the United Nations. And she has founded mumsDU (Mothers United and Mandated to Saving the Lives of Drug Users), a Canadian network that connects parents who have lost children to illicit drug use and encourages harm reduction policies specific to opioid addiction.

“I wouldn’t be doing this if it wasn’t Jac’s request,” May says of her advocacy work. She travelled from her home in Mississauga to Vancouver earlier this year to participate in an invitation-only roundtable of frontline workers, researchers, and drug policy specialists to share knowledge and best practices for addressing B.C.’s overdose crisis, which killed a record 931 people in 2016.

In the first three months of 2017, 347 British Columbians died of illicit drug overdoses, at least three people dying every day. The January-through-March numbers for this year already exceed the total number of people who died of illicit drug overdoses a decade ago. The BC Coroners Service reported 202 overdose deaths for the whole year 2007.

May is calling on the federal government to decriminalize illicit drugs. “Substance users will do what they need to do to get their substances. And that’s because we have criminalized it. We have turned them into criminals in order to support their habits,” she says.

“As a parent, if I did it all over again, I would go as far as to purchase the drugs myself. Pharmaceutical grade. I would do anything I had to do to work with her through it.”

Substances users, she says, need support and resources, not punishment and deprivation. What, for May, is harm reduction? “To know that a person’s there to support you through it. That is it,” she says. “I wish I had used that practice with Jac. I really do.”

She wishes she could have supported Jac through her addiction. She wants to find ways to reduce the harms around substance use so that people in Jac’s position can survive rather than die like she did.

All of this work has been pivotal to May’s own process of healing and of moving through grief. “It changed me in ways that I never thought possible,” she says. “It changed my way of thinking. It changed my way of living. It changed my way of how I view my own self-worth.”

“You learn so much so late.” ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: