We're going to hear a lot about third parties and vote-splitting as we approach the May 14 election. That's because everybody who knows anything about B.C. elections knows one big thing.

As a Young Liberal delegate said during last fall's annual party convention: "The only time the NDP wins is when the free enterprise vote is fractured."

The Liberals and Social Credit before them have been saying the same thing for more than half a century. When Martyn Brown was campaign director for the BC Liberals in the 2001, 2005 and 2009 elections, he worked that line like a government mule.

"It is a powerful argument, no doubt," he has written, "one that I helped elevate to an art form in my long time in B.C. politics. It certainly helped elect Gordon Campbell's three successive majority governments."

There are, however, a couple of problems with the argument. For a start, as Brown now concedes, it misses the point by ignoring why people vote for third parties. It's based on an outdated Cold War mentality. It also ignores how voters shift allegiance in elections. And it oversimplifies history.

As political scientist Norman Ruff wrote after the 1996 election -- one of the key events in free enterprise vote-splitting mythology -- "there has never been a monolithic free enterprise vote in British Columbia."

As we shall see, B.C's alleged free enterprise coalition has waxed and waned, shifted and scattered over the years. Sometimes the shifts have meant an NDP victory; usually they haven't. And such shifts also happen on the other side of the spectrum. In an odd mirror image, you will hear New Democrats complaining about "their" voters splitting off to the Green party, foiling the NDP's bid for power.

"I think it's a vanity the major parties have that the voters for third parties really belong to them," Ruff, professor emeritus at the University of Victoria, said in an interview.

Martyn Brown's change of tune

Brown, who spent almost a decade as chief of staff to former premier Gordon Campbell, examines the vote-splitting argument in detail in his ebook, Towards a New Government in British Columbia. The argument doesn't hold water, he concludes.

Still, he said in an interview, the caution against splitting the free enterprise vote is a powerful weapon.

"The reason it's employed is because it is readily received as being true," said Brown, who has also served as a senior election campaign official with the Social Credit and B.C. Reform parties. "From both the left and the right. The NDP have equally made the argument: split the vote and you elect the other guys.

"Where it misses the point is why people vote for those other parties... Sometimes it's to register their protest, sometimes it's to embrace their values and more often than not it's because they're disaffected with the parties that had temporarily held their support in a fluid coalition."

People who vote for third parties often do it because they like their values, Brown said. Parties like the BC Conservatives and the Greens aren't necessarily arguing about who should form the government; instead, they're arguing about what ideas you should vote for, he said.

The argument against splitting the free enterprise vote also ignores the way voters behave by assuming there is one universe of NDP voters and another made up of anti-NDP voters, with no crossover.

The last few polls from Angus Reid Public Opinion suggest that about 15 per cent of voters who supported the Liberals in 2009 now intend to vote NDP. Ruff, the political scientist, cautions that this finding is based on respondents' memories of how they voted last time, which may not be totally reliable. And, he adds, he has "old school" reservations about Reid's online polling methodology.

(Note: Pollsters currently use a number of different techniques to reach prospective voters. Online polling is viewed with caution by some, but has proven to be accurate in recent elections. For a discussion of polling techniques, see this article from The Tyee's archives.)

Reid's numbers, if accurate, refute the idea that the majority of British Columbians are anybody-but-the-NDP voters.

How big is 'NDP's universe'?

The kinds of shifts suggested by the Reid poll have always happened in B.C. elections, said Brown.

In 1991, Brown was an official with the campaign of the governing Social Credit party. On Election Day, the Socred vote went way down, the Liberal party vote went way up and the NDP formed government. Pundits and Socreds called it proof of the old argument against vote-splitting.

Except, Brown said, the Liberals took votes away from the NDP.

"If that had just been a two-way race between the Socreds and the NDP, you probably would have seen the NDP pushing 60 per cent -- 55 to 60 per cent," he said.

"The NDP's universe is much, much larger than most people assume it is. And the Socreds knew this and so do the Liberals today."

Some 59 per cent of respondents to the latest Reid poll say they want a change in government, and 29 per cent of former Liberal voters agree, Brown noted. That says the NDP universe is much larger than the 47 per cent who told the pollster they would vote NDP if a vote were held today.

Coalitions are fluid, Brown said.

"There's always what we call swing voters and that's why they're called swing voters. They're able to move from one party to the next and they're not terribly wedded to ideology."

None of this is to say that mainstream parties don't try to stop supporters from switching to third parties. Between now and May 14, the Liberals will be fighting to woo supporters back from the Conservatives, just as the NDP will be fighting to suppress the Green vote.

But vote-splitting mythology is founded on two claims that get repeated over and over. One: every time the free enterprise vote splits, the NDP gets in. Two: the NDP only gets in when the free enterprise vote splits. As we'll see, history doesn't support either statement.

History's lessons

Back in the 1940s, B.C. was governed by a formal centre-right coalition. Backed by big business, the Coalition government rose from the Great Depression and the early years of the Second World War and it existed, at least in part, to keep the socialists out.

By 1952, the coalition government was looking old, tired and weak. The coalition fell apart and a new government was formed by the upstart Socreds, who would be seen as the new centre-right coalition for the next 20 years.

In every one of the seven elections that Social Credit leader W.A.C. Bennett won, the "free enterprise" vote was split. The Liberal party took 25 per cent of the popular vote in 1952 and it continued to take about 20 per cent of the vote for as long as Bennett won elections.

By 1972, Bennett's government was long past its best-before date. It was seen as old, tired and out of touch. On Election Day, the free enterpriser's nightmare came true. Vote splitting, it was said, defeated Social Credit and let the NDP swarm into power.

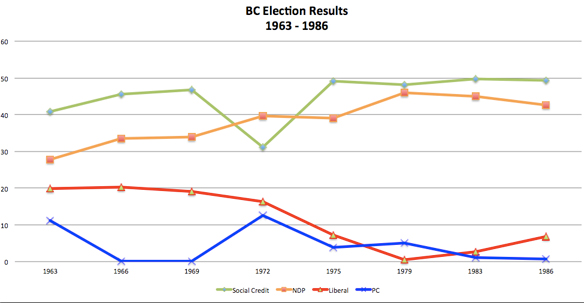

But consider this chart:

The Socred vote dropped 15 percentage points between 1969 and 1972. And the Liberal vote dropped, too, by about two-and-a-half points. So you can't accuse the Liberals of vote splitting. Must have been the Conservatives, whose vote jumped 11 percentage points.

But this is where UVic's Norman Ruff enters the picture again. He has run the numbers from that election; even if every Conservative vote had gone to Bennett, the Socreds still would have lost. The result would have been much closer, but the NDP still would have pulled out a narrow majority government, Ruff said.

Between 1969 and 1972, the NDP vote jumped more than five points. Those votes had to come from somewhere. Maybe some former Socred voters did the unthinkable and -- not content to merely split the free enterprise coalition -- actually switched sides and voted socialist. Or maybe a lot of former Socred voters jumped to the Liberals at the same time that an even bigger tide of former Liberals was switching to the NDP.

In 1975, a revitalized Social Credit, led by W.A.C.'s son Bill, turfed the NDP. Mini-WAC, as he was known, built a new coalition, raiding MLAs from the Liberal and Conservative parties, and took almost 50 per cent of the vote -- better than his father had ever done.

The NDP vote held steady in '75, and the Liberal and Conservative votes dropped sharply, giving some fuel to the vote-splitting myth. But even then, as Brown notes, centre-right third parties took 11 per cent of the overall vote.

The Liberals and Conservatives didn't collapse entirely until the 1979 election. But when they fell, former Liberal and Tory supporters don't appear to have bolted to the free enterprise alternative.

Instead, as the third parties waned in '79, the Socred vote declined by one point and the NDP vote jumped almost seven points. The Socreds won by just over two points, Bennett the Younger's narrowest victory.

The party Bill Bennett helped revive held power until 1991, when the coalition fell apart again.

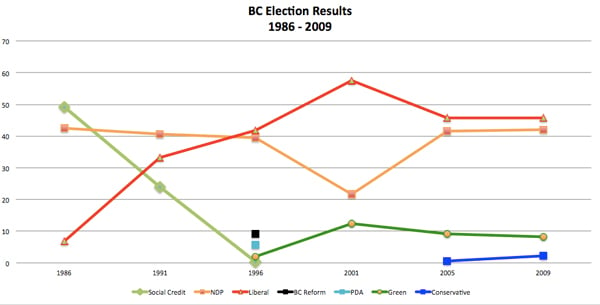

Riddled with scandals, discord and perpetual general wackiness, the 1991-model Socreds saw half their vote disappear in one of the strangest B.C. elections ever. With the campaign winding down, the NDP appeared set to win in a landslide.

Then Gordon Wilson, leader of the seemingly moribund Liberal party, rode a solid debate performance and a wave of media attention to opposition status. As Brown argues above, by Election Day the Liberals were splitting the NDP vote.

By 1996, voters had turned against the NDP. The Liberals -- without Wilson -- had become the main free enterprise party. New Liberal leader Gordon Campbell, who was pretty unpopular himself, alienated voters in the North by promising to privatize BC Rail and shrink the legislature -- thereby reducing the representation of the North.

B.C. Reform took more than nine per cent of the vote, good for two seats – both of them in the North. The Progressive Democratic Alliance, headed by Gordon Wilson, took almost six per cent of the vote and one seat. Even though the Liberals won more votes overall than the NDP, they lost in the seat count.

That's what happens when you split the free enterprise vote, said pundits and Liberals. If those northerners had stuck with the Liberals instead of voting Reform, Campbell would have won.

Brown, who was working for B.C. Reform in the '96 campaign, argues that the Liberals could have won a majority in that election with better campaigns in only six key ridings. With an extra 704 votes in only two of those ridings, they could have formed a minority government.

With a better campaign in those key ridings, Brown writes, "the BC Liberals would have won and the arguments about free enterprise vote-splitting would have been all but mute."

This case also points up the vanity aspect of the vote-splitting argument. Anti-vote-splitting logic implies that northerners should have gone to the polls intent on keeping the NDP out at all costs – but in this case doing so would have meant voting against their own economic and democratic interests.

Clearly, they weren't prepared to make that sacrifice. Which just goes to show that even a powerful tool like the vote-splitting myth will get you only so far.

Want to learn more about the BC 2013 election and your riding? Visit The Tyee's Election Map and Guide.

![]()

Read more: BC Politics, BC Election 2013

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: