"It's all about the herring," an anthropological researcher named Iain McKechnie said to me at a dinner party about a year and a half ago.

I scoffed. Herring?

Like most fish-swilling West Coasties, I was a devotee of salmon, British Columbia's iconic wildlife symbol. I was there every year for the running of the salmon, at whichever spawning stream was handy. I consulted my wallet-sized card and bought the salmon approved by Ocean Wise. I ate salmon grilled, baked, cured and smoked. I was even embarking on a book about the relationship between people and salmon.

Why should I care about the herring, that little silver bulldog of a fish that didn't have the grace to die after spawning? Sure, it had high Omega-3s like salmon, but really! Herring?

Little did I know that I was about to enter the opposing camp, the herring camp. For McKechnie was only the first of a growing crowd of researchers, environmentalists and First Nations activists who wanted me to shut-up, already, about the damn salmon. What was emerging from the scientific record, they said, was a past world much richer, more diverse, and decidedly less salmon-centric than most people suspected -- a world that had something to teach us about living in balance.

McKechnie, of the University of British Columbia, was the first but by no means the most vociferous of herring advocates I was to meet. That distinction belongs to Dana Lepofsky, an archaeologist at Simon Fraser University and a powerful engine in the drive to understand the complexity of ancient fisheries. At my last encounter with Lepofsky she was wearing a bright-blue T-shirt that read "I [heart-symbol] Herring" and she brought to her lecture the scrappiness of the herring legions. "My goal, as an activist and lover of herring," she said, "is that we make herring a household word -- that it's as loved up and down the coast as salmon."

Scientifically, Lepofsky's goal is to map the historical -- and pre-historical -- diversity and abundance of stocks other than salmon, using oral histories from First Nations communities and zooarchaeological data as part of the process. To that end, she has assembled a multi-disciplinary team of herring researchers at SFU and other institutions: ecologists, archaeologists, fisheries biologists and representatives of the First Nations. It is called -- touché, salmonistas -- The Herring School. Graduate students associated with The Herring School, as uppity as Lepofsky in their dedication to reassert the place of the little silver fish in the ecosystem, came up with the blue T-shirts.

Bones in the mud

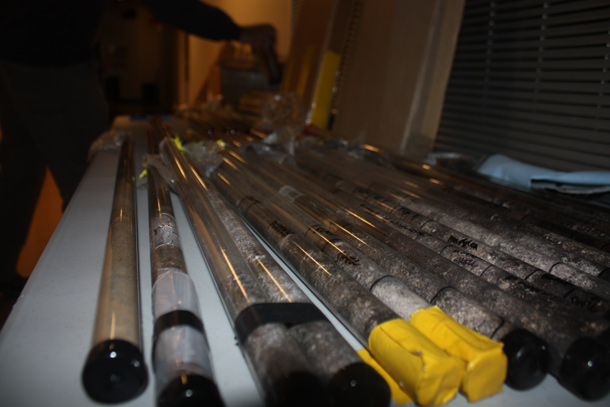

What McKechnie does to advance the herring cause is search for tiny bones in Barkley Sound, off the west coast of Vancouver Island. He uses corers -- plastic tubes -- to extract layers of mud, and augers to haul up shells and fish bones from village sites, some of them 5,000 years old. The corer lets him read layers as deep as seven metres. Across the island from McKechnie, in Comox Harbour, Megan Caldwell, from the University of Alberta, has already learned that the people using fish traps perhaps 2,000 years ago were stalking herring -- not necessarily salmon. And at Burrard Inlet, the fjord that separates the city of Vancouver from the North Shore Mountains, Nova Pierson, a Simon Fraser University graduate student, has found that herring and other small fish were exploited continuously for 3,000 years and were crucial to the well-being of communities. Salmon were prized, the herring students admit, but their portion on ancient plates rose and fell, an indication that people might have been concerned about over-exploiting a resource.

All three students do something a little different: they use at most a two-millimetre mesh to screen fish bones. The commonly used six-millimeter screen is too big to catch the bones of herring.

It isn't only salmon-eaters, then, who discriminate against herring: standard methods of research have long jaundiced the scientist's view. The quest for better methods recently led one University of Victoria archaeologist, Quentin Mackie, who works at sites in Haida Gwaii, off B.C.'s northern coast, to try sifting with mosquito nets. "You bring back half the site to the lab," he said. "Not viable."

Using water to wash debris helps in finding small bones, but it's labour-intensive and expensive. And there is always a trade-off: careful perusal of small samples yields otherwise overlooked fragments, but a quick wide overview of an area is valuable too. So refocusing the research lens to include small species is no easy matter.

The over-representation of salmon bones in the archaeological record is only one culprit in skewing our notion of ancient coastal ecosystems. Recent local extinctions of herring populations and the presence of invasive species, like mitten crabs, that damage fish habitats messes with our perceptions of what diversity was in the pre-historic scene along Canada's beaches.

Ghosts of herring past

I caught up with Caldwell in early spring at Gibsons Beach, an hour and half ferry ride across from Comox. The beach is a 15-minute paddle by canoe from the Tla'amin First Nation main reserve and about 130 kilometres north of Vancouver. Armed with an industrial-sized tape measure, a compass, and clipboards, Caldwell and Nyra Chalmer, from SFU, were surveying the beach. A blue heron stalked the water's edge behind them and an eagle twittered from one of the tall trees lining the rocky shoreline. As the tide receded before them, a rock pattern emerged -- a circle and chevron shapes that pooled water. It was a fish trap.

Caldwell and Chalmer were mapping the fish trap, along with other features of the beach that might help tell the story of an ancient people's eating habits. Although other sites in the Tla'amin territory go back more than 7,000 years, the material from Gibson Beach is only a few hundred years old, from just prior to European contact. When the blue heron plucked a fish from the water, though, we were quite sure it wasn't a herring: Tla'amin no longer has a herring fishery.

Caldwell spent countless hours during the winter in a lab at SFU, sifting through dirt -- bags and bags of Gibsons Beach midden samples stored on metal racks -- and using tweezers to pick out herring bones and other faunal remains. (I've watched her at it and wondered whether herring lovers have X-ray vision: I tweeze up a bone the size of a pine needle and, with a glance, Caldwell pronounces, "Cleithrum, probably from a herring. It's part of the pectoral girdle, it sits behind the gills.")

After walking the beach with Caldwell and Chalmer, we get in our cars and drive five minutes to the main village of Tla'amin territory to get another angle on local fishery history. The village is called Teeshoshum, which translates to "Waters White With Herring Spawn," and a generation ago, it still deserved the name.

The front yard of the village is a sandy beach with stone walls that scallop the shore for a kilometre -- sunken fish traps that echo the pre-Colombian-era remains that Caldwell and Chalmers were mapping -- and that still catch the odd fish in season. I found Michelle Washington, land use coordinator for the Sliammon Treaty Society, in Tla'amin's administrative offices.

"When I was a kid, this time of year was alive, this village was alive," she said as she placed a number of studies on the table, one was a land use survey she authored. "Everybody had their smokehouse ready, their herring racks ready, the kids were all down the beach, you know little kids just had ice cream buckets, the bigger kids had bigger buckets, because you could go down into the little pond in the intertidal zone and scoop up hundreds of herring in one scoop and run it to your house. That's not that long ago: 1984 was the last year I remember that happening."

Washington is only 40, young enough that in many families she might have grown up ignorant of Tla'amin traditions, but she was curious about the old ways and spent time with her grandparents as a girl. Over the years she has also interviewed lots of elders. One of the things she learned was the interplay of environment and people: stone traps invited in the herring, precisely when salmon stores were low (early spring) and villages needed an influx of fresh food. Animals and people danced an annual cycle together.

As land use coordinator, Washington is determined to help set the record straight, to show what the ecology of the Tla'amin territory looked like during thousands of years of human occupation. But repeating the story of the Tla'amin herring catch can be painful, especially if it has no effect. Management practices would have to change fast enough to restore the Tla'amin catch in her lifetime.

In the summer, Lepofsky brought Washington along with dozens of scientists and First Nations representatives, to SFU for a Herring School Workshop, and Washington's sadness echoed through the narratives of many of the aboriginal people. Barbara Wilson from Haida Gwaii ended her presentation with an honest comment. "It's very hard," she said just before leaving the microphone stand, "to again step up and give information."

There is an impatience, among scientists and First Nations alike, to restore herring fisheries. They all know that though the stories are readily available, the rest comes slowly: the research and the political haggling and the bureaucratic tinkering and the awakening of the public that could, someday, restore the fisheries.

Still, the stories at the workshop were wonderful -- of the Sitka, Alaska, herring spawn fishery, where Harvey Kitka has for more than 60 years employed traditional methods; of the Heltiusk nation's joyous harvest when the herring spawned and ecosystem exploded with life, which 85-year-old fisherman Edwin Newman recounted in vivid detail; of the Haida glossary that Wilson assembled for the Ee ung, which is what the Haida call herring. They have a word for milt in water --k'aajii -- a word for the movement of herring in water -- skiidguunang -- and a word for each of the four kinds of kelp on which the herring spawn. (Haida Gwaii has sites more than 10,000 years old yielding herring bones that likely were processed by people.)

The archaeologists and ecologists hung on the Haida's herring lingo, keen to soak up observances and practices passed on to Wilson and others, from a time before newcomers came from Europe, coastlines crowded up, and the attentive ways of living with fish died out, along with the rich diversity of the waters.

"When you lose a gathering site or a species, you lose all the practices, the songs, and the language that goes along with that cultural activity," Washington told me, as we looked over a map of traditional fishing, hunting, and foraging areas in Tla'amin territory. Tla'amin has a few fluent speakers but a language disappears in fits and spurts. The language of fading traditions dies first, and even a linguistic revival might fail to include language specific to such a lost resource as herring. So the narrative has been interrupted on many levels. It's frustrating for Tla'amin and other indigenous communities.

A few communities still depend on herring. The Yu'pik, for example, on the Bering Sea near Nelson Island, Alaska, have traditionally had plenty of herring and few salmon. But in many areas, commercial and aboriginal fisheries alike have declined.

Everybody's lunch

Nearly 200 true herring species -- of the family Clupeidae -- swim the temperate ocean, but what we commonly call herring are the Atlantic (of which the Baltic herring is a subspecies) and the Pacific. These, and all the true herring, are forage fish, which means they live near the surface and are the main breakfast, lunch, and dinner for a slew of predators. Silvery, with a single dorsal fin and the jutting lower jaw that gives them a bulldog look, herring are also distinguished by having no lateral line -- the organ that, in many fish, senses vibration or movement. They're also known to fart, that is, a herring communicates by blowing air out its anus -- it does this at night with lots of other fish around.

The lifespan of a herring averages 10 years, and some probably live for 20 years or more. Those that migrate may grow as big as a pink salmon. And like salmon, they usually return to their natal waters to spawn.

Herring populated the Pacific Ocean about 3.5 million years ago, colonizing waters from northern Baja California to northern Alaska, and across to Japan and Russia. The most productive North American herring habitats extend from B.C. to southern Alaska, an area that was covered by an ice sheet more than 11,000 years ago. When the glaciers retreated, it is possible that herring were among the first fish to show up, drawn by phytoplankton and zooplankton. It's possible to argue, then, that the pioneering herring lured both salmon and people to our continent.

Commercial herring harvests on the West Coast began a scant 140 years ago. The catch peaked in the early 1960s and collapsed soon after. Here's the way evolutionary biologists explain the collapse:

Overfishing removed most of the older fish from the gene pool, which promoted a "live fast, die young" population. Young, small fish had to reproduce early; older, bigger fish -- the kind that produce more eggs -- did not get to pass on their genes.

The federal government closed the West Coast commercial herring fishery for four years after the collapse, allowing only traditional and bait fisheries. Herring numbers climbed, and in 1972, the government established a roe fishery that remains dominant today. Yet three of the five identified stocks managed by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans still have no commercial fishery: Haida Gwaii, the Central Coast, and West Vancouver Island. The two that do, Prince Rupert and the Georgia Strait, are likely not what they once were. And trends in consumption remain a worry. High-end herring roe from B.C., for example, a traditional New Year's gift in Japan, is in less demand by young Japanese who are, well, less traditional.

Reviving the runs

Part of the fervor of the herring researchers is to pinpoint why particular herring runs have dropped and not recovered. Overfishing and shoreline development are obvious culprits. And some decline may be random: small, abundant species that reproduce quickly tend to have populations that yo-yo. Genetic isolation, too, may doom local populations. In the Georgia Strait as a whole, for example, the herring fishery is quite healthy, while the Tla'amin herring population within the Strait has tanked.

It is hard to assess population diversity in herring, because populations mix before they go off to spawn. Before the development of the automated genetic sequencer in 1986, efforts to distinguish herring stocks focused on reproduction rates, the kinds of parasites hosted, or growth rates -- all imperfect markers because they're affected by environmental conditions. Today, efficient, affordable DNA analysis is yielding useful results.

At the University of Washington, Lorenz Hauser's studies of Puget Sound herring populations has revealed that the severely depleted Cherry Point herring is an isolated, genetically distinct population distinguished by late spawning times in exposed areas. Segregation, and the vulnerability it brings, appears in many cases to arise from distinct spawning times.

Researchers hope that DNA from ancient herring bones will likewise help distinguish regional herring populations and their vulnerabilities. Camilla Speller, a postdoctoral fellow in the archaeology department at the University of Calgary, is on that track, having identified 43 unique DNA sequences from 85 specimens.

I'll have the herring

It is embarrassing to admit that it was only at the Herring School Workshop last summer that it dawned on me that, as far as I knew, I had never eaten a herring. At a local grocery store I asked the clerk behind the seafood counter if only pickled herring was available, what about fresh? He told me to call any morning, except Sunday, before 11 a.m. They could order frozen herring for an afternoon delivery.

On a Saturday morning after the workshop, I called and as luck would have it, a friend answered the phone at the fish counter with the news that fresh herring, caught off Vancouver Island, had just been delivered. "We only get fresh herring about four times a year," he told me on the phone. "Why do you want them?"

I guess it seemed absurd that I would eat them. "Hold a few for me," I said. "I'll be right down."

"No hurry," he said. The store would be buying 10 pounds; it usually only sells about seven.

Eight herring, each about the length of my forearm, freshly gutted, ended up costing me $6.51. Scored and salted, placed on a barbecue, five minutes on each side, they were delicious. I was an instant convert. They had a taste similar to the meatiness of salmon without the bombast. It was a taste sensation that was subtle and deep. From my hours picking through lab samples with Caldwell, I recognized the larger bones, and even came up with a name or two. As for the smallest, the only option was to crunch and swallow.

I thought of what Lepofsky had said one day as she guided a group of students to archaeological sites on Quadra Island, just north of Comox, about biological impoverishment darkening our vision of the past. The ecological baseline has shifted so severely, she said, that when we look to the past, we can't see its diversity. I thought, too, about Washington and her frustration at the pace of our learning. It made me realize that my own herring conversion -- writ large -- was part of the goal of the Herring School.

Since that first conversation with McKechnie, I'd started to look past salmon. If the Herring School could get the rest of British Columbia to do that -- or even a tenth of us, even the foodies who want to make dinner choices matter -- they'd be getting somewhere. ![]()

Read more: Food, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: