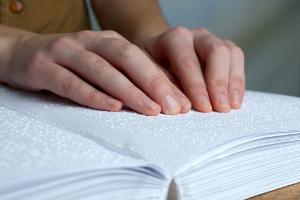

Countries from around the world last year reached agreement on a landmark copyright treaty designed to improve access to works for the blind and visually impaired.

As the first copyright treaty focused on the needs of users, the success was quickly billed the "Miracle in Marrakesh" (the location for the final round of United Nations negotiations) with more than 50 countries immediately signing the treaty.

The pact, which was concluded on June 27, 2013, established a one-year timeline for initial signatures, stating that it was "open for signature at the Diplomatic Conference in Marrakesh, and thereafter at the headquarters of WIPO (the World Intellectual Property Organization) by any eligible party for one year after its adoption."

In the months since the diplomatic conference, 67 countries have signed it. The list of signatories includes most of Canada's closest allies, including the United States, European Union, United Kingdom, and France. The major developing economies such as Brazil, China, and India have also signed the agreement. Curiously absent from the list of signatories, however, is Canada.

Digital locks impede access

Canada's failure to sign the treaty is particularly surprising given the important role it reportedly played in facilitating a deal. Reports from Marrakesh indicated that Canada worked to find common ground and helped craft the final agreement. Moreover, from both policy and legal perspectives, supporting the treaty would appear to be a proverbial no-brainer.

The treaty expands access for the blind by facilitating the export of works to the more than 300 million blind and visually impaired people around the world, which is needed since only a tiny percentage of books are ever made into accessible formats. Further, it restricts digital locks from impeding access, by permitting the removal of technological restrictions on electronic books for the benefit of the blind and visually impaired.

The treaty would require few changes to Canadian law. The basic requirements of the treaty are an exception or limitation in national law that permits the creation of accessible format copies for the blind or visually impaired without permission of the copyright holder as well as a scheme to permit the cross-border exchange of qualifying copies.

Canada already has an exception in national law relating to persons with perceptual disabilities. The current exception is not identical to the treaty requirements and would need some modest tweaking to comply with the new international standard.

Deadline looms

The biggest change would likely come from the need to establish an entity that would facilitate, promote, and disseminate accessible format copies of work and exchange information with other countries about accessible works. In other words, the treaty would require Canada to invest in improving access for the blind.

Given the narrow goals of promoting greater access for the visually impaired, signing the treaty should be relatively uncontroversial. Indeed, while both the U.S. and European Union expressed some concerns during the negotiation process, both are now signatories.

With a copyright review planned for 2017, Canada could sign the treaty now with the expectation of incorporating the necessary reforms as part of the next reform process. Alternatively, there are several bills currently before the House of Commons that involve intellectual property issues that could be amended to include the necessary changes.

Regardless of what legislative approach is adopted, the first step is for Canada to sign the treaty before the June 27 deadline. Failure to become part of the initial group of signatories would raise troubling questions about why the government was unwilling to take a strong stand in favour of the rights of the blind and visually impaired in Canada. ![]()

Read more: Politics, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: