Like the four million others who had purchased Three Cups of Tea, I was moved by Greg Mortenson's story of how he came to build schools in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Back in 2007, the book's focus on cross-cultural understanding and forging strong grassroots relationships with local communities seemed to provide a much-needed counterweight to news stories about the Taliban, suicide bombers, and realpolitik manoeuvring by western states in the Middle East and central Asia. In view of increasing troop deployments to Afghanistan, and mounting combat and civilian mortalities with no end in sight, Mortenson seemed to offer a higher-minded, peaceful and effective strategy to address the roots of terrorism.

I read the kids' version of the book, Listen to the Wind, to my son several times while he was in kindergarten. The picture book version depicts Mortenson's journey to the impoverished community of Korphe, where he is nursed back to health after a failed mountain-climbing venture, and where he decides to build his first school. My son had heard about the war in Afghanistan and had asked about the reasons behind the conflict and the casualties. I wanted him to have a more balanced, complex view of the situation that would go beyond media stereotypes of intolerant hostile religious fanatics or passive, hapless victims. The book showed him that there were children just like him living in that part of the world, who had parents and leaders that deeply valued what education could bring to their communities.

Growing up familiar with women's equality, he found it unfair at first that most of the schools were built for girls. He didn't understand why girls would be deprived of an education and married off at 12 or 13 to become second or third wives to much older men. "Why would they want girls to get married so young?" he queried. "The husbands want more babies," I answered, trying to avoid a complicated exegesis of sexual dynamics, gender relations and fundamentalist religious practice until he was older. But this puzzled him even more."Why would they need all those babies?" he asked. My explanation that young girls would be brought into families to act as unpaid servants with few rights finally seemed to satisfy him, along with the reassurance that some of the schools were geared for both sexes.

For his next birthday party, my son and I agreed to ask his friends to donate their spare pennies toward the Pennies for Peace program to support schools built by Mortenson's organization, the Central Asian Institute (CAI). As some of his friends were not only keen penny collectors but also keen donors, he managed to raise about $32 worth of pennies. Then we counted and rolled the pennies together, lugged them to the bank, asked for a bank draft and mailed it off. I hoped to show him that his efforts could make a positive, concrete difference. He was excited to get a note of thanks about a month later. Feeling inspired by the success of his first fundraising effort, he would choose various other charities to support at his next few birthday parties.

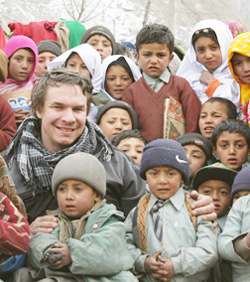

A year and a half ago, my sister bought tickets for us to hear Greg Mortenson give a talk in Vancouver about his second book, Stones into Schools. As a speaker, Mortenson seemed humble, sincere and knowledgeable. Like his missionary parents, Mortenson had an important message, albeit a secular one, to impart to the rapt masses that filled local high school auditoriums. When he talked about his work with senior officers in the U.S. military and at U.S. military academies, I felt a twinge of surprise. This seemed a huge shift for a man who had written about being interrogated by the CIA regarding the whereabouts of the Taliban and Osama Bin Laden, and who'd struggled late at night to painstakingly type out letters to potential donors across the country. With the overwhelming success of his first book, Mortenson had clearly been accepted as part of the mainstream. Soon afterward, U.S. President Barack Obama donated $100,000 from his Nobel Peace Prize to the CAI.

'Three Cups of Deceit'

Then, earlier this year, a 60 Minutes exposé aired on television, alleging that Mortenson's first book contained fabrications and inaccuracies. During the show, a fellow mountaineer and former supporter, author Jon Krakauer, dismissed Mortenson's tale about recovering in Korphe after being lost in the mountains as untrue. (Krakauer even published an online book, Three Cups of Deceit, detailing his accusations.)

A spot check by 60 Minutes investigators of 30 of the schools CAI had allegedly built were shown to be either empty or built by other organizations. Some schools stated they had not received CAI funding for years. Also shown to be false was one of the more gripping anecdotes in Three Cups of Tea about Mortenson's kidnapping by the Taliban in 1996. Mortenson and the CAI board refused requests to be interviewed for the show.

Soon afterward, Mortenson and the CAI issued rebuttals. Mortenson stood by the facts in his book, although he acknowledged that there may have been some compressions and omissions. Since that time, class action lawsuits have been launched against Mortenson in Montana and Chicago.

I wondered what to tell my now nine-year-old son. How would he deal with the possibility that the man depicted as a hero had allegedly used over half of donor funds not to build schools, but to hire private jets and finance the promotion of his book? Would disillusionment and cynicism replace idealism, would he hesitate or even refuse to support any apparently good cause again?

Given that blind trust and blind optimism can be as dangerous as their opposites, I decided to tell him a few key facts about the controversy. It did look like Mortenson had built or supported a significant number of the schools overseas. He and the CAI continued to issue statements insisting that 100 per cent of funds raised through the Pennies for Peace program had been put directly toward educational initiatives in Pakistan and Afghanistan. However, sufficient doubt had been cast on the book and the CAI to warrant a thorough and independent audit to determine if there had been any misappropriation of donor funds. It did seem probable that Mortenson's story about being kidnapped by terrorists was made up to inject drama into his book and enhance his reputation. But the possibility remained that he might be partially vindicated. Time would tell whether this particular idol had feet of clay -- or merely a few toes' worth.

The Santa Claus factor

Would partial vindication be enough? Of course, we try to teach kids that lying is wrong. Feeling ambivalent, I'd always given vague answers to my son's questions about Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy while going through the motions of leaving milk and cookies beside the glass-enclosed gas fireplace and rooting around in the dark under his pillow to replace lost teeth with loonies. I hadn't the heart to undermine other kids' illusions and destroy their parents' elaborate make-believe rituals. In this case, however, I hoped that laying the groundwork for critical thinking and healthy scepticism might be helpful in the long run. (Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy had never relied upon donations to fund their private jets in any versions I'd heard!)

Even the comic book heroes and fictional characters in novels are multi-dimensional, with storylines based on that kernel of truth about human nature and the human condition: good guys aren't always wonderful, and bad guys are not always evil. On the one hand, there are times when issues are clear cut along binary ethical poles; but on the other, they sometimes lie somewhere in between, although admittedly, moral relativism can be a slippery slope.

Even though I was dismayed by the allegations myself, I wasn't shocked. There have been many exposés over the past years of non-fiction writers posing as other people. Most recently, Tom MacMaster, a 40-year-old married American graduate student living in Scotland, was revealed to have authored a blog purportedly written by a 35-year-old Syrian lesbian, Amina Abdallah Araf al Omari. The "Gay Girl in Damascus" hoax fueled outrage amongst Syrian activists and overseas, especially in light of the internet campaigns resulting from "Amina's" supposed detention by Syrian security forces. White, middle-class author Margaret Seltzer wrote a critically acclaimed novel under the pseudonym Margaret B. Jones, pretending to be a half Native American foster child raised by gang members in south central Los Angeles. Other recent literary hoaxes include the infamous J. T. LeRoy scam and Misha Defonseca's fraudulent Holocaust memoir. In any of these cases, even if the hoaxes served a higher end (e.g. improved treatment for addicts, social programs for the disenfranchised) the ends never justifies the means. A betrayal of trust can do significant damage to legitimate causes.

Memoirs and truth

Mortenson's situation seems most akin to that of James Frey, who had embellished his best-selling addiction memoir, A Million Little Pieces, with exaggerations and fabrications. Having shaped legal submissions built on "relevant" facts in my brief past career as a lawyer, and being a writer now myself, I know there can be a fine line between truth and fiction. That line is clearer with journalism, as in the notorious case of reporter Jayson Blair, who during his five years at the New York Times fabricated quotations from sources, wrote about events that never occurred, and plagiarized from other news outlets.

Memoir as a genre can be a bit more problematic. It incorporates many of the techniques of fiction in terms of developing characters, conflict, narrative arc, and dramatic tension. Dialogue and scenes might be recreated according to underlying emotional truth as opposed to factual accuracy. There will always be many different points of view and interpretations of any one event. Memory can be faulty. As author and instructor Madeleine Blais has put it, "truthiness" might be the best that can be hoped for in the case of most memoirs.

"But did Greg Mortenson lie about being kidnapped by terrorists?" my son asks. Wasn't it the young kid in the story who pointed out that the emperor had no clothes? Clearly, something like being held hostage by the Taliban can't be fudged, and my son knows it. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: