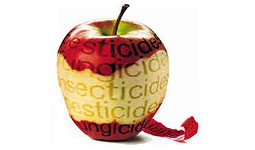

Canadian parents can be forgiven for feeling panic today, convinced that they, or their children, are at grave risk of contracting any one of a number of horrible diseases. The reason? They had applied Weed N Feed to combat the dandelions in the lawn, or put a flea collar on the family dog, or even allowed their children to eat non-organic apples that had somehow, somewhere, come into contact with a pesticide.

The panic, while largely unjustified, stems from a report made public last week by the Ontario College of Family Physicians, which concluded that pesticides are so toxic that there may well be no safe level of exposure.

Spokespersons for the College spoke of a litany of health problems they believed occurred from pesticide exposure, ranging from various cancers to learning disabilities and depression. They said they would begin to encourage Ontario doctors to advise patients to avoid all pesticide exposures, not even eating food that had been exposed to pesticides if it was at all possible to avoid it.

Their comments were based on a 179-page report prepared by a committee of the College whose members had spent the past year reviewing as many previous studies as they could find on the effects of pesticide exposure on human health. Although a number of media reports described the work as "the largest study" ever done in Canada on pesticide exposure, the team did not conduct any clinical or epidemiological investigations itself. Its work was limited to reviewing studies others had done.

And therein lies the problem. The team was stuck with those other studies, with any methodological flaws they contained, and most especially with whatever groups it was that those other researchers had chosen to study.

Few ordinary families studied

When their work is studied in detail, it becomes apparent that almost none of the studies used involve ordinary families who put a flea collar on the dog or eat non-organic produce or even use pesticides once or twice a year to get rid of the tent caterpillars on the trees or the weeds in the lawn. Rather, a high proportion of the studies cited involve people who are exposed to pesticides at very high dosages, very frequently, and, far too often, without proper precautions being taken. They are people who work in factories where pesticides are made, or farmworkers who labour day after day among pesticide-laden plants, or golf course workers who are applying herbicides to fairways and greens on a regular basis.

Even worse, many of the workers studied were employed in countries where worker safety regulations are virtually unknown. They were banana workers in Ecuador, pest-control workers in India, potato farmers in Colombia, to name just a few examples. In some cases, the studies also looked at the children of the farmworkers and pesticide applicators.

Unquestionably, the studies showed that, over-all, those who were subjected to those high levels of exposure were at greater risk of developing some cancers, some reproductive problems, some chromosomal aberrations. Those who conducted the studies were the first to admit that it was extremely difficult, even in those cases, to determine just how great the increase in risk was. That's because it's very hard to winnow out the effects of the pesticide exposure from that of other contaminants to which such workers are exposed, ranging from other chemicals used on farms to animal viruses. All the same, the cumulative results of the studies are certainly strong enough to state that strict regulations should be put in place to protect farmworkers and others who must be exposed to high levels of pesticides in their jobs.

More difficult, however, is to take those findings and try to decide what they could mean for that average homeowner or gardener. The Ontario doctors choose to interpret the data as meaning that any level of exposure must, therefore, be dangerous, especially to pregnant women or children.

Accidents, not fruits and vegetables, the big risk

But that conclusion is not inherent in the studies themselves. Only a very few of the studies suggest any link at all between low-level exposure and health problems.

And not a single one suggests that eating fruits or vegetables that have been treated with pesticides poses a measurable health risk.

Most of the other cases of serious harm cited involve accidental poisonings by pesticides - people, especially small children, who ate or drank relatively large amounts of pesticide because they were unaware of what it was or of the dangers of taking in large amounts of it. The results of those studies stress the importance of storing pesticides where children can't get at them and ensuring they remain clearly labeled in their original containers. (A number of poisoning cases have occurred because people have transferred the pesticides to empty pop bottles for ease of application, but haven't relabeled the bottle to make it clear that it no longer contains Coke or 7-Up.)

However, in order to reach their conclusion that all pesticides should be avoided in all circumstances, the Ontario doctors are relying on what is known as "the precautionary principle." The report describes this principle: "When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken, even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully understood."

When precautions do more harm than good

In many cases, the precautionary principle can be applied with few unintended negative consequences. But the pesticide study is a good example of where its application could actually cause more health problems than it could ever prevent.

Pesticides can greatly benefit human health where they are used to kill, for instance, insects or rodents that serve as vectors of potentially fatal diseases. Millions of lives are saved in tropical countries by using insecticides to kill mosquitoes that would otherwise spread malaria. Even here in North America, the use of larvicides against mosquitoes may prevent the spread of West Nile virus which has killed hundreds of people across the continent in the past three years.

More indirectly, the use of pesticides to produce cheaper, more accessible fruits and vegetables over-all produces a significant health benefit. Eating fruits and vegetables protects against some types of cancers. Those who eat lots of fruit and vegetables rather than processed high-fat, high-sugar foods are much less likely to be obese, to contract heart disease and to suffer from adult-onset diabetes. But if someone decides that it is safe to eat only organic produce, their over-all consumption of produce may well decline unless they can afford the significantly higher prices of organic items.

The Ontario family doctors have doubtless done the country a favour by raising awareness of potential problems. No one suggests any more that chemical pesticides should be a first line of defense against any insect or weed infestation.

But a detailed read of the studies also shows that no one needs to panic because the dog is wearing a flea collar and the children are eating lots of produce, even if it isn't all organic.

Barbara McLintock is a contributing editor to The Tyee. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: