"There is nothing so powerful as truth -- and often nothing as strange." Daniel Webster

When a writer is born, a family is destroyed, or so goes a famous truism. In the case of Truman Capote, a writer was born, and a family was blown to bits with a shotgun, but the two events only became related later on.

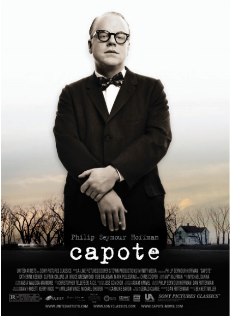

Capote, the latest biopic about a famous person and his infamous doings begins in 1959, when the writer was researching and birthing his big bad baby of a book (In Cold Blood). The notion that writers will sell everyone they know down the river is evidenced by Capote himself, who sold out his subjects and his soul in return for a masterpiece of journalism. He got what he paid for, and so do we. There are no big surprises in this film. What you expect is exactly what you get: lots of Philip Seymour Hoffman acting up a storm and the other players adding more subdued, sedate performances.

It's a bravura one-man-show that feels somehow oddly empty, as if the void that existed in Capote himself is made manifest on the screen. The film does, however, pose some interesting questions about whether art is above morality. It's a moot question.

Small town planet

This film begins with an opening shot of wheat blowing in the wind. It is the late 1950s, and America is about to undergo all types of storms and squalls, but in Holcomb, Kansas, change is nowhere to be seen. This is small town America, full of girls in prim sweaters and men in fedoras. Into this staid place wafts Capote, with his Blanche Dubois manner and expensive clothes. The clothes jump out at you, not only as a statement of character and social function, but as the delineating line between high, low and middle class people. It's the drapes versus the squares; the bad men wear greasy duck-ass haircuts, and black leather jackets, and the good hardworking citizens don clothes from the Sears Roebuck. And Truman himself, with his camel hair coats, cashmere scarves (from Bergdorf's) and impeccable suits, is a visitor from another, much more fashionable, planet.

But despite his fancy wrappings, Capote also came from mean beginnings: an alcoholic mother who abandoned him. He's got poverty, pain and the dark side of Southern charm. He was, in essence, made for the story he was about to tell.

Director Bennett Miller's restrained approach has a clean, spare feeling that screams "QUALITY PICTURE!!!" but it's so quiet and understated, that the story occasionally threatens to disappear. The raunch that characterized Capote's work is nowhere to be seen here. The murder of an entire family, which precipitated Capote's trip to Holcomb, is initially given short shrift. The only blood in evidence is a discreet splash on the bedroom wall. As Capote sets about infiltrating the society of Holcomb, shots are interspersed of his other life as the toast of New York's glittering parties. Possessed of a skewering wit, and meanness to match, he was, often quite literally, a scream.

To kill a friend

More interesting, and indeed, more human, is Capote's childhood friend, Nelle Harper Lee who was busy producing her own masterwork To Kill a Mockingbird at the same time as she was acting as Capote's research assistant. Harper Lee (Catherine Keener) is the only presence that seems truly trustworthy. It's up to her to provide gravity and judgment, and she acts as the film's moral compass.

Capote and Harper Lee were friends, possibly even co-authors; they complemented each other well. Capote claimed that he had actually written large portions of To Kill a Mockingbird, and his spirit is evident in that book in the character of Dill, the odd little boy described as a "pocket Merlin, whose head teemed with eccentric plans, strange longings, and quaint fancies." Like the character of Dill, darkness drew Capote "as the moon draws water." Whether or not Capote actually ghosted Harper Lee's novel, these two works; To Kill a Mockingbird and In Cold Blood, stand as two very differing interpretations of the American experience. There are curious parallels. In one story, a brother and sister escape murder; while in the other, they do not. One might be fiction and the other horribly real, but the differences are negligible, "Actual drama, though technically a fiction, is...a search for truth," says David Mamet.

The six years that Capote spent bringing the book to life, ended with "a snap and a thud" when Perry Smith and Richard Hickock were hanged. There is something horribly parasitic about the book. So too, the film: despite its sheen and polish, it has an unsettled hollowness.

Slow motion crash

In the collision between Perry Smith and Richard Hickock, and the Clutter family, the two intersecting narrative lines move ever closer, it's the inevitability of their eventual meeting that gives Capote's book such force. The ending is preordained -- like most tragedy -- all the reader does is watch it play out.

What it needs, of course, is someone to tell the tale. And here, the writer is a lawless entity whose ultimate loyalty is only to his art. Perry Smith, as the sad shadow of the glittering, sleek Truman, is appropriately underplayed by Clifton Collins Jr. The scenes with Capote and Perry Smith are unnerving with their subtext of mutual usage, desire and constant manipulation. Who is the bigger user is difficult to determine, the charming murderer or the charming writer?

Capote's book offered the somewhat startling notion that murderers might be as much victims as their actual victims. The idea that acts of sudden, atrocious violence don't strike like thunder from a clear blue sky, but are laid down by years of systematic violence and abuse is old news to us jaded modern people but to the 50's naïfs, it struck horribly home. The horror of people randomly murdered in their beds used to sell newspapers, books, and of course, films, comes with its own horrors, to which numbness is the only reaction currently available.

The other stated purpose of Capote's book was to undermine capital punishment, even though the idea that the writer needed his subjects to die in order to end his book, is deliberately, and bluntly, stated throughout. Perry's jailhouse confessions are depicted with blond head and dark head bent together, bonded together by a terrible need to be seen. It is this one quality, more than ego, or ambition that seems to unite this unlikely pair.

Hard luck manipulation

Smith and Capote shared the same hard-luck childhood story of death, alcohol, suicide and abandonment -- one wrote, one killed -- but whether Capote's book was also a form of self-murder is the question that the film ever so quietly asks. If you sell your soul for art, the devil will eventually come calling. He accepts booze, pills and all major credit cards. Capote might have been a liar, a drunk and a general all-around jerk according to the many people that he variously used and abused, but he was one hell of a writer. But then again, Picasso and many other "great men," were great at being artists, and not so great at being men. Where sociopath ends and artist begins, is the central question. There is, of course, no answer.

The book seemed to have sucked Capote dry by the end of his life, but the parasitic nature of writers couldn't find a greater champion than Capote who used his way with words to construct an entire persona -- the society swans, the black & white balls, appearances on Carson etc. -- but to then also systematically dismantle that very spun-sugar edifice, biting the pretty manicured hands that fed him. Having struggled so mightily to escape his meager upbringing, the glamorous world of high society and Hollywood must have seemed heaven to this fey young man from the South. The realization that they were simply another version of hell may have prompted Capote's later social suicide in book form.

The genre of true crime fiction, which gets a special little section in the bookstore all to itself, was virtually spawned by Capote's work. From In Cold Blood to Henry, Portrait of Serial Killer, it's a hop, skip and jump from art to exploitation. Nonfiction seems the dominant mode of popular culture lately, but whether you can lay this heavy mantle on the elfin shoulders of Tru, is difficult to say. Capote believed that In Cold Blood, would change the way people wrote, and he may have been right. The later years of drugs, self-immolation and death are alluded to in the final epigram of the film taken from the words of Saint Theresa of Avila "There are more tears shed over answered prayers than over unanswered prayers."

In the life of Truman Capote, those were often the same thing.

Dorothy Woodend reviews films for The Tyee every Friday. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: