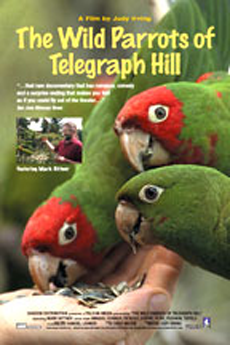

First penguins, now parrots: who would have thought that the bird-brained would have so much to teach us about humanity? Judy Irving's documentary The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill is equally about animal and humans. It seems we all have the same problems, the same wants and desires: a warm place to sleep, enough to eat, and someone to love us.

The central character of this extremely gentle film is a guy named Mark Bittner, who has lived on and off the streets of San Francisco for close to twenty years. He's a bum, but a Dharma bum, which is a critical distinction. Like many people who simply don't fit in, Mark has spent many years of his life looking for the right path.

When Bittner first moved to the city by the bay, his first intent was to become a rock star. But over time, he found himself doing a series of increasingly odd jobs. Nothing quite worked out for him until he stumbled onto the parrots. As part of a job looking after an elderly woman, he got a free apartment and a lot of time on his hands. In that free time, he started feeding some nearby parrots. Over the course of a year, Bittner was gradually able to build up the birds' trust, and come to know them by sight and personality. Eventually, he became known as the Parrot Guy of Telegraph Hill, another variation on the Bird Man of Alcatraz, and this led a documentary filmmaker to the door of his tumble down cottage.

Mind of a parrot

This is another one of those recent documentaries that is making fictive films seem somewhat irrelevant. Is there anything more curious than real life, whether that life is human or animal? Bittner remarks in the film that he was first drawn to the parrots (cherry-headed conures) because "they didn't seem like birds at all but more like monkeys." And after observing them intensely, he begins to see and eventually understand their behaviour.

The existence of a parrot is not an easy one: there are hawks to watch out for, jealous quarrels, lost loves, fights, death -- the whole egg, as it were. Time is the kicker here. You need a great deal of it to begin to observe and comprehend. The line between sentience and sentience gets a little fuzzy, as Mark comes to understand his feathered friends more deeply. Mark becomes an amateur ethologist by accident, but then again, maybe there are no such things as accidents.

This film raises deeper questions about why anything happens the way it does. Life and death are tricky: sometimes, it's a hawk that gets you; other times, it's the slow creeping sadness of disease. Like the story of Tupelo, the first bird that Bittner cares for, that dies, or Mingus, the Jekyll and Hyde of birds.

Nests on margins

There are many theories on how the flock on Telegraph Hill came to be, but the most obvious answer is that they all escaped, in one way or another, and made another life for themselves, eating local fruits and foraging in people's gardens, much like Bittner himself. He is an odd duck who lives partly upon the beneficence of strangers; little old Italian ladies give him free bread, and another couple let him live in their cottage rent free.

But everything must pass, and Mark's idyll also must end. The couple that has let him squat decides to renovate their property (with a few uneasy glances at the camera). In fact, the film becomes a portrait of the city of San Francisco and how it has changed since the time of the Dharma bums and beats like Kerouac, Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti. Like most major American cities, the tiny little hidey-holes, where people could scratch out an existence, are becoming fewer and fewer.

People like Bittner are forced into the margins, not because they're crazy but simply because they don't fit in: much like the parrots themselves who have been captured from the jungles of Peru, sold as pets in the US, but will do basically anything to remain free. Their very existence prompts an ornithological debate. Because they're not native species, some bird experts suggest that the entire flock should be captured and exterminated, raising questions about what makes one type of life more valuable than another.

Free fall

The strange parallels between the lives of birds and humans continue when Irving films the various species that make up San Francisco, including the Pigeon Lady and a few other rather wild looking individuals. Bittner quotes nature poet Gary Snyder, who said, "If you want to find nature, start where you are." Many of the ideas that Snyder has devoted his life to percolate like an underground river in this film.

Although there are obvious comparisons to other human-watching-animal stories like Never Cry Wolf or The March of the Penguins, the more immediate relation is to another literary form. We live in an age of memoir and this film with its highly personal slant feels like a memoir movie more than a straightforward documentary. It's a natural evolution, but of course, that's what nature does best as well: evolve, and survive. The more you observe animals the more you realize animals and humans are much the same.

This is also the conclusion that Bittner comes to. He quotes a Buddhist parable that compares life to one big river. When a river goes over a cliff, the water separates into a billion tiny individual drops, but when it hits the bottom of the cliff, the drops come together once more. Life occurs in that brief moment of free fall. What you do with that moment is of course, the big question, or one of them anyway.

Birds vs. birdies

The other day my mother was talking about how there are really three life crisis moments. One is in your early twenties when you're trying to figure out who you are, another in your late thirties when you're trying to decide if it's too late to change who you are, and a final one in your late fifties, when you ask yourself what you should do with the last third of your life and how to make it profound and meaningful.

Although many people in North America apparently choose golf as some sort of path for their remaining years, there are other traditions. In India, it is perfectly proper to give everything away and become a wandering sadhu in search of enlightenment. In North America, you can become a bird watcher, which will save you from looking too kooky but still allow you to ponder the ineffable and the unknowable through the eyes of birds.

Dorothy Woodend reviews films for The Tyee every Friday. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: