If you think sex between humans is complicated stuff, I have some news for you. Turns out that the torrid affairs of lusty sapiens are pretty vanilla compared to the wild world of insect love.

This might not come as much of a surprise to anyone who had the opportunity to take in Isabella Rossellini’s Green Porno films. The series of shorts explores the copulatory rites of different members (heh…) of the bug world with perverse genius.

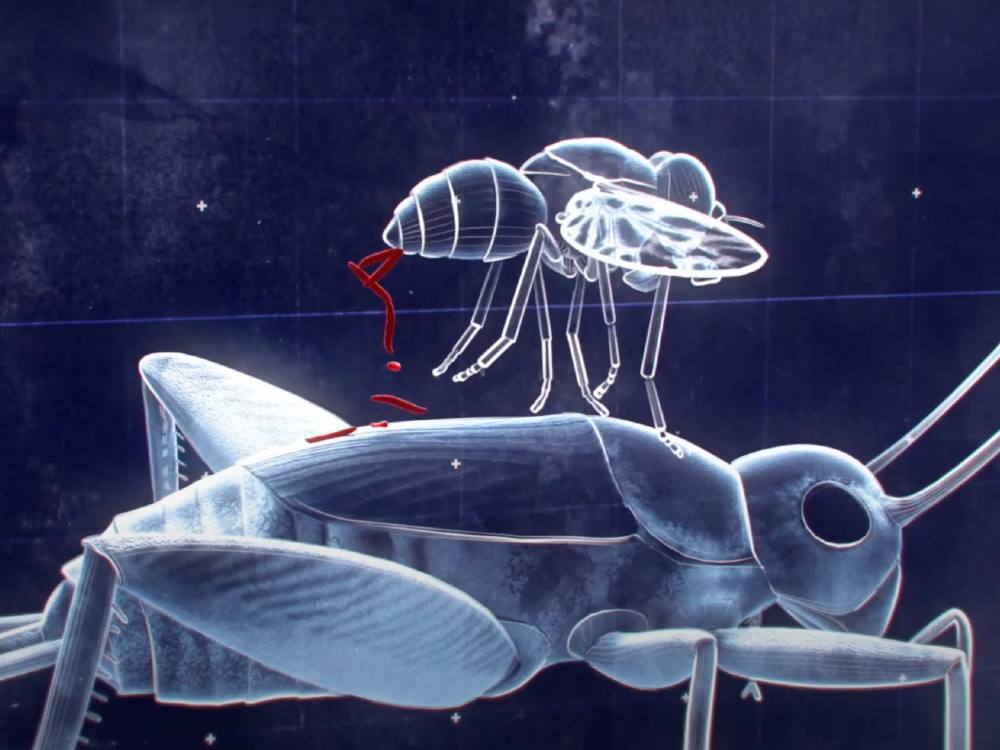

Although the new nature documentary Bug Sex doesn’t quite scale those same horny heights, it’s still packed full of fascinating information. But first you have to get past how the show’s earnest host and Vancouver titan of environmental advocacy David Suzuki says the word “sex.” A little too much relish on that hot dog, I say. But who can blame him: sex is the stuff of life, as well as a good reason to get up in the morning.

As Suzuki informs us at the outset, there are more than 10 quintillion insects on the planet, vastly outnumbering humans. How bugs make even more bugs is only the beginning of a vast contemplation of the basis of life itself. To be blunt: it’s almost too strange.

Director Andrew Gregg doesn’t shy away from the outré information, but it is ecologist Maydianne Andrade who sums it up best. “Sex in bugs is fascinating, gruesome, counterintuitive, ridiculous in its complexity, ridiculous in how extreme it is. And most people know nothing about it.”

The documentary sets out to rectify this. And rectify it does!

Sex screams

Fruit flies might be some of the freakiest little guys. For one thing, a male fruit fly’s sperm can be 20 times the length of its body. But the sexual habits of Pacific field crickets, black widow spiders, monster haglids and dance flies are equally as wild.

Turns out that the people who study the reproductive proclivities of bugs are also some pretty fascinating creatures.

The ecologist Andrade and her husband Andrew Mason from the University of Toronto research the auditory habits of monster haglids, large prehistoric-looking insects capable of making noise that rivals a rock concert.

In a section appropriately titled “Shrieking Monsters of the Bush,” the pair hunt down the bugs in forested areas near Hinton, Alberta. Capable of emitting a mating call that comes in at about 105 decibels, the males scream out a sexy siren song that the females follow.

Well, it’s not exactly that simple. Sometimes the females come around with amorous intent. But more often it’s other males who show up spoiling for a fight. Male haglids are extremely territorial, claiming individual trees and then loudly yelling about them to anyone who cares to listen. Much like some human men.

A louder sound is a stronger defense, but it also demonstrates to the females that the males are propertied creatures, capable of defending their turf from, um, all comers, if you will.

If and when sex does occur, the male sweetens the deal with a set of special pads hidden under his wings that the female eats while the act is taking place. Other times, same-sex relations occur between two males, although no one is exactly sure why.

Down and dirty

There are many remaining unknowns about why insects do the things they do. This might be due, in part, to the fact that women scientists have only recently begun to enter the field. As one scientist notes, the study of female insect courtship behaviour (largely led by women researchers) didn’t really get rolling until 2013, whereas male reproductive habits have been studied since the 1900s.

As another researcher wryly explains, the most extreme sexual behaviours didn’t just suddenly come out of the blue, but in only focusing on male sexual behaviour, half of the story was missing. The sexual cannibalism of wolf spiders is a case in point.

On the coast of Uruguay, researcher Anita Aisenberg pays close attention the amatory habits of Allocosinae spiders. She explains that her attraction to spiders came about in part because of their badass reputation, which inspired her own sense of personal rebellion.

As she hunts spiders in the sand dunes, she explains that sexual habits of the Allocosinae are some of the more unusual in the spider kingdom, in that it is the females who come a’courting.

The male digs deep burrows in the sand, which the female enters when she is looking for some down and dirty action. She dances about, waving her arms/legs in an enticing display, and if all goes well, the deed proceeds. Sometimes all the waving in the world doesn’t work, though, and he eats her.

Aisenberg gives a heavy sigh after witnessing this act of sex cannibalism. Nature red in tooth and claw and all.

Meanwhile on the Hawaiian Islands, evolution is in overdrive with the behaviour of male field crickets. Marlene Zuk, her husband John Rotenberry and their research assistant examine an unusual development in the sexual behaviour of the crickets.

The mating call of males had the unfortunate effect of attracting not only prospective mates but also parasitic flies. Over the course of only a few generations, male crickets have largely gone silent out of a need for self-preservation.

So, what about the sad lonely females wandering the islands, looking for love? It sounds a lot like the Vancouver dating scene.

As Zuk explains in the film, the most interesting aspect of this situation is how quickly the crickets have adapted. Over the course of five years, within three to four generations per year, males have largely lost the wing structure that allows them to make noise. It is one of the fastest mutations ever witnessed by scientists.

The loss of sexual signal is an indication of how quickly sex can drive some of the most extreme adaptations, hence its attraction to scientists and researchers who can witness this type of change taking place almost in real time.

The ultimate sacrifice

On Vancouver Island, Catherine Scott and her partner Sean McCann flip fallen logs. They’re looking for black widow spiders and their smaller, more benign-looking mates. The reputation that female black widows carry as man-killers isn’t quite what it seems. It’s more often the male of the species who practice a form of sexual self-sacrifice.

As the males approach the females, they carefully announce their intentions by plucking individual strands of her web, communicating that they’re not prey, but would-be lovers.

After mating, males will often somersault into the female’s open fangs, offering themselves as a meal, the idea being that if she is satiated in every way, she’ll be less likely to get it on with another male. By allowing themselves to be eaten, the males also ensure that they can deposit more sperm, meaning their spider babies will have a better shot at coming into existence.

Food and sex are often combined in insect sex acts. In dance fly populations, males of the species present treats, called nuptial gifts, to the females as an enticement for sex. The females attract the males by inflating their abdomens and displaying their hairy legs.

If this doesn’t sound too different from the human world, picture this: while the females are eating dead midges, the male mates with them, soaring through the air in a three-way stack, called a flying triplicate. Picture doing that on your next date.

Insects genitals are also fascinating, in that they often break off, plug up and other somewhat startling stuff. In the face of all this extremity, the bigger question of pleasure lingers. Do bugs experience it? The answer, according to Dr. Lisha Shao, from the University of Delaware, is a definite yes.

The two things that fruit flies love best in the world are alcohol and sex. But when given a choice, they choose sex. The role that pleasure plays in evolution is, in the realm of insect research, still pretty new stuff.

As the film makes clear, we have barely scratched the surface on insect sex, given how many insects are on the planet and how little is known or understood about their reproductive habits.

In the midst of watching the film, it’s hard not to extrapolate about what would happen if some of these behaviours were to take place in the human world.

Probably best not to think on that too long and hard, but one has to give Mother Nature full props for wild imagination and the try-everything-at-least once approach. She’s one kinky MILF.

‘Bug Sex’ premieres on March 10 on CBC’s 'The Nature of Things.' ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: