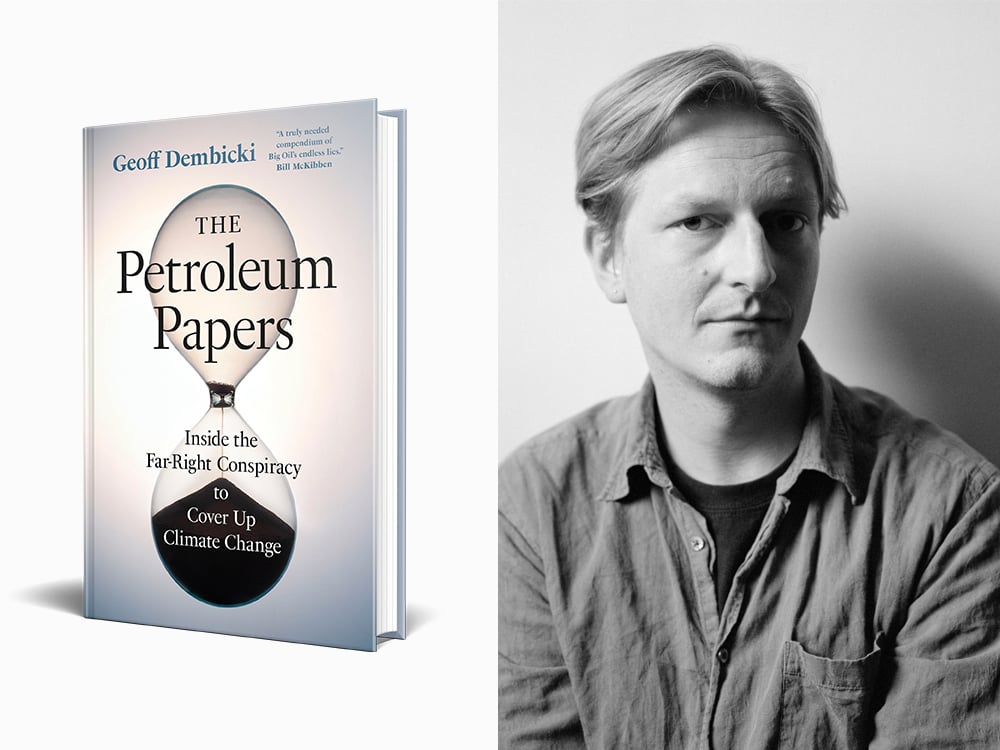

[Editor’s note: This is excerpted from the highly praised new book 'The Petroleum Papers' by Geoff Dembicki, a deeply researched, gripping expose of how Big Oil and its backers have long known the threat of climate change but relentlessly averted chances to stop it. Read an interview with Dembicki and attend The Tyee launch of his book on Sept. 20.]

On a November day in 1959, one of the most powerful people in oil and gas received a credible warning that his industry could cause death and suffering for large numbers of the planet’s inhabitants.

The warning came during an event in New York City called “Energy and Man,” a daylong symposium that was attended by government officials, historians, economists, scientists and fossil fuel industry executives — more than 300 in total. Organized by the American Petroleum Institute along with Columbia University’s Graduate School of Business, the event was described as “an inquiry into the role of energy, past, present and future, in the lives of each of us.” It was also a celebration of the industry’s 100th year of existence.

Robert Dunlop was among the attendees that day who walked up the stone steps of Columbia’s Low Library, passed by Ionian columns and bronze busts of Zeus and Apollo, entered a foyer containing a white marble statue of Athena, and then a library reading room lined with green marble columns topped with gold. Dunlop presented himself as the successful 50-year-old businessperson that he was: black tie, horn-rimmed glasses, not a trace of stubble and hair slicked back and meticulously parted to the side.

He was the second speaker at this gathering of postwar power brokers, and he opened his 35-minute speech with a not-so-subtle metaphor.

“It pleases me to note that on its hundredth birthday, the petroleum industry is not a tired, old industry. The petroleum revolution is not history, but is a current, pulsating event, still unfolding,” he told the crowd lasciviously. “Under the thrust of competition, which was midwife at its birth, petroleum developed as an industry of great independence and vitality, as a restless innovator which continuously shook up the status quo.”

Born in Boston, Dunlop attended the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce at the University of Pennsylvania and graduated at the top of his class in 1931. He was soon after hired as an accountant by Sun Oil, at the time a large regional oil company in the U.S. northeast. Sixteen years later, at the age of 37, he was named president, and under his leadership Sun Oil expanded aggressively across the United States and into Canada and Latin America.

“Endowed with remarkable recall — always remembering the names of employees after an initial meeting — Dunlop was serene and pensive, as well as sometimes self-effacing, often referring to his accounting roots but obviously proud of his superb technical prowess,” his alma mater would later describe him.

Dunlop was at Columbia that day not only as head of Sun Oil but as a director of the American Petroleum Institute, a trade association founded in 1919 which by the late 1950s had become the main research and lobbying group for the U.S. oil and gas industry. It was also a leading source of fossil fuel propaganda.

A black-and-white film produced by the institute during this period showed two oil company geologists stepping off a helicopter onto an Oklahoma prairie potentially containing new supplies of petroleum. “You are looking at men on a hunt,” the narrator explains. “The game they seek is not a living thing, and their weapons are not firearms, but they are hunting, and they are armed — with the weapons of science.”

During his speech that day, Dunlop sought to describe the challenges of early oilmen like Edwin Drake, who had drilled the first successful U.S. oil well in 1859. His phallic metaphors now turned biblical. “At least one man was purported to have argued with Col. Drake that his idea was immoral; that the oil was needed down there for the fires of hell, and to withdraw it was to protect the wicked from the punishment which they so just deserved,” Dunlop said. “While this proved not to be the last criticism directed against the petroleum industry, it was at least among the most novel.”

A century after the industry’s founding, Dunlop projected confidence about the decades ahead. “To me, the future appears to hold great opportunities for the oilman,” he said in New York.

However, Dunlop hinted cryptically at challenges to come: “There are aspects of the future which are clouded by the penetration of non-economic forces into the functioning of an industry which has always performed best in an atmosphere of economic freedom.”

Dunlop didn’t say what storm clouds specifically threatened the expansion of oil and gas. But the next “Energy and Man” speaker did. That speaker vividly described a new and unexpected threat to the industry: its vast and growing emissions of a greenhouse gas called carbon dioxide.

Edward Teller was no back-to-nature romantic. The scientist who took the podium after Dunlop was known primarily for his lead role in creating the world’s first weapons of mass destruction. Teller was part of a secret government team at Los Alamos, New Mexico, that during the 1940s developed atomic bombs that were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, causing the deaths of over 200,000 people. Yet Teller began his talk at Columbia by warning of a threat that was potentially greater than nuclear destruction. “And this, strangely, is the question of contaminating the atmosphere,” he said.

Teller tried to ease his audience into a concept many of them were likely hearing for the first time. “Now,” he explained, “all of us are familiar with smoke and smog and all of us know about it as a nuisance.” Teller went on, “I would like to talk to you about a more hypothetical difficulty which I think is quite probably going to turn out to be real. Whenever you burn conventional fuel, you create carbon dioxide. It has been calculated that the carbon dioxide which has been put into the atmosphere since the beginning of the industrial revolution equals approximately 10 per cent of the amount of carbon dioxide that our atmosphere contained originally.”

This was a fairly avant-garde statement for the time, but not unprecedented. Scientists had first described the ability of gases in the atmosphere to trap planetary heat during the 1800s, and in the early 1900s Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius was one of the first scientists to link this warming to human activity, calculating the greenhouse gases released by burning coal. By the 1950s, the science was becoming more precise through the work of people like Roger Revelle at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, who along with Hans Suess of the U.S. Geological Survey showed the oceans are limited in their ability to absorb carbon dioxide. Most of the gases released through our use of fossil fuels, they calculated, end up in the atmosphere.

Depictions of global warming’s impact on human society were also starting to enter popular culture. Several years before Teller attempted to alert his New York audience, an article in Time magazine warned that CO2 building up in the atmosphere could by the early 2000s “have a violent effect on the Earth’s climate.”

It’s no coincidence that Teller was aware of the latest climate science. During the same period when it was funding early atomic research, the U.S. military was also looking closely into earth sciences. This included Project Gabriel, a classified study of the impact of nuclear weapons on weather patterns launched by the U.S. Weather Bureau in 1949. In subsequent studies, military scientists sought to figure out through models the best weather conditions for explosions and how detonating nuclear weapons could affect the natural world. It was during the course of such research that these scientists first coined the term “environmental sciences.”

Teller knew the audience at Columbia might find it hard to be too concerned about carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that can’t be seen by the human eye and poses no immediate danger to people’s health. “So why should one worry about it?” he asked. Teller then provided an intro to the burgeoning field of climate science: “[CO2’s] presence in the atmosphere causes a greenhouse effect in that it will allow the solar rays to enter, but it will to some extent impede the radiation from the Earth into outer space. The result is that the Earth will continue to heat up until a balance is re-established.”

The impacts, he warned, could be catastrophic. “It has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10 per cent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York,” he said. “All the coastal cities would be covered, and since a considerable percentage of the human race lives in coastal regions, I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe.”

This wasn’t the first time Teller had delivered such a warning. In late 1957, he’d spoken to members of the American Chemical Society about the impact of burning coal and oil, stating that the carbon emissions coming out of chimney and exhaust pipes could someday change the climate and melt a large portion of the polar icecaps. This had apparently caught the oil industry’s attention. In October 1959, the month before Teller’s Columbia speech, Royal Dutch Shell scientist M.A. Matthews published a paper saying he didn’t think Teller’s prediction would come true because “nature’s carbon cycles are so vast that there seem few grounds for believing Man will upset the balance.”

Yet there is reason to think many of the oil executives and industry representatives hearing Teller’s speech in New York were learning about climate change for the first time. “Could you please summarize briefly the danger from increased carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere?” the dean of the Columbia Graduate School of Business, Courtney Brown, asked following Teller’s talk.

“Our planet will get a little warmer,” the nuclear scientist responded, explaining that global CO2 levels would grow exponentially if we continued to burn petroleum and other fossil fuels. “It is hard to say whether it will be 2 degrees Fahrenheit or only one or five. But when the temperature does rise by a few degrees over the whole globe, there is a possibility that the icecaps will start melting and the level of the oceans will begin to rise.”

“Well,” Teller went on, “I don’t know whether they will cover the Empire State Building or not, but anyone can calculate it by looking at the map and noting that the icecaps over Greenland and over Antarctica are perhaps 5,000 feet thick.”

There is no historical record of how Dunlop or any other oil industry executive in the audience reacted. But the Sun Oil CEO was apparently paying close attention, having promised during his own speech to “listen with the keenest attention this afternoon to Dr. Teller.” What Dunlop heard that day is one of the earliest known climate change warnings to the oil and gas industry. The products his industry hunted, extracted and sold, the oil executive now knew, were capable of someday flooding the very city where his industry’s hundredth birthday celebration was taking place.

In 1963, Robert Dunlop crossed his nation’s northern border to visit what would decades later become one of the biggest oil and gas operations in the world. At the time, however, the site was a remote patch of boreal forest in northeastern Alberta.

It had been nearly four years since the Columbia University “Energy and Man” conference, and if Dunlop had taken Teller’s warning about climate change seriously, his actions didn’t reflect it. During those intervening years one of Dunlop’s top priorities as president of Philadelphia-based Sun Oil was to figure out a way to commercially develop the Canadian oilsands, a deposit that by some estimates contained more petroleum than all of Texas, and even the entire Middle East. ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: