Joseph Trutch’s name is finally coming down.

The lieutenant-governor of B.C. from 1871 to 1876, Trutch was known for malicious hostility towards Indigenous people. He did everything in his power to whittle away their land rights, like shrinking the size of their reserves. In a letter to his mother, he compared them to dogs and called them “the ugliest and laziest creatures I ever saw.”

In 1886, the City of Vancouver named a street after him in a nice part of the West Side. It’s in Kitsilano, stretching north from 18th Avenue all the way to the water, with a sweeping view of the inlet and the mountains.

In July 2021, 135 years later, city council unanimously voted in favour of a renaming. Mayor Kennedy Stewart called Trutch a racist, saying “he doesn’t deserve to have a street.”

Debate around names seems to be everywhere in recent years, as Canadians and Canadian institutions reckon with the ugliness of the nation’s colonial past.

It’s a huge legacy to confront.

Trutch Street may be in the process of being renamed, but what about McBride Park, just a block away? It was named after the anti-immigrant B.C. premier who wanted to shut out “Asiatic hordes” to prevent the “extinction of white people.”

It’s left me wondering if there’s a racist behind every monumentalized name. Was Oak Street named after a racist? Or was it just named after the tree?

You really never know where Vancouver’s place names come from. South Vancouver’s Bobolink Park might appear to be named after the bobolink blackbird, but it was actually chosen as a tribute to the Bob O’Link golf course in Illinois.

A CBC analysis found that a third of B.C.’s 358 schools are named after settlers and notable Britons. Among them, bigots like McBride and men with no connection to Canada. These guys are indeed immortalized everywhere.

Toponymy — the study and discipline of place naming — is growing in importance, with extensive policies and experts making decisions in committee, from the United Nations down to cities.

It’s an “anguishing” responsibility, members of Vancouver’s Civic Asset Naming Committee have said. The committee, formed in 2012, ponders weighty topics like privilege, particularly concerning white, male supremacy; a far cry from when city engineers and surveyors needed a name for a new street and asked staff to bounce ideas around.

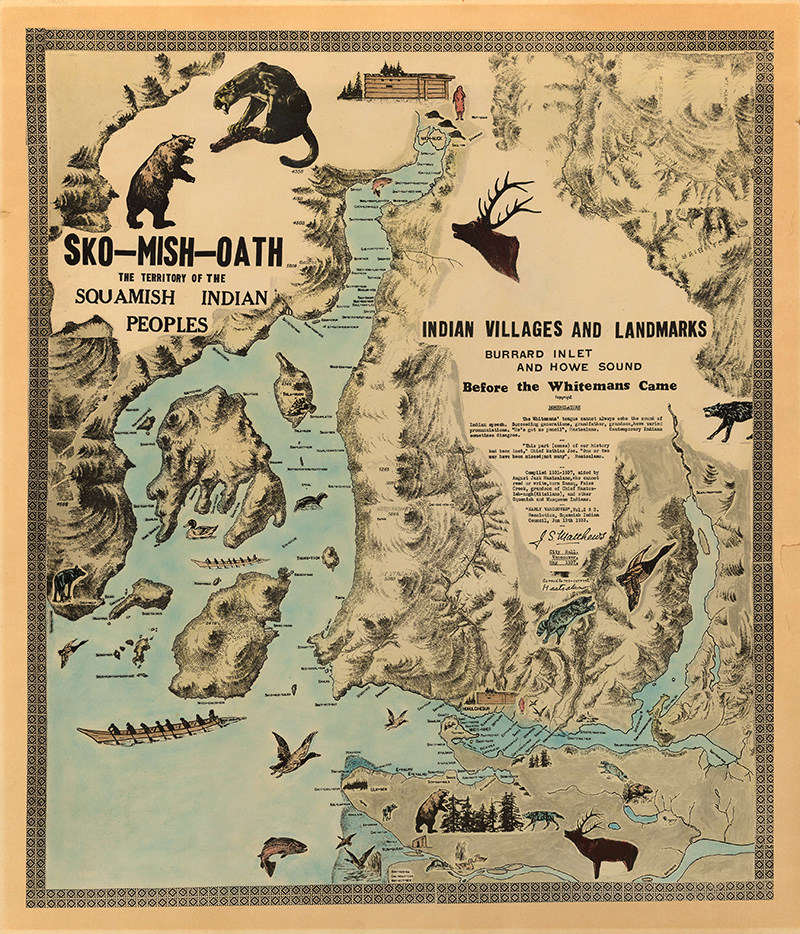

Local historian John Atkin, who used to chair the Vancouver naming committee, says bringing in Indigenous names in particular is important work so the people who live here today understand that their home did not begin with colonization.

“We’re a blip on the time scale of this territory,” Atkin said of British settlement and the nation-building that followed. He calls for more acknowledgment of the people who lived here for millennia and still live here. Using their place names is part of that.

“We need to reset the balance.”

What were our civic forbearers thinking? There is a Simpsons episode that makes fun of civic naming. In a motel room, Springfield’s Mayor Quimby asks his sexy date, “How would you, uh, like a street named after you?”

“How would you, uh, like a street named after you?” pic.twitter.com/4sz8ZrVbLm

— SimpsonsQOTD (@SimpsonsQOTD) February 20, 2020

It’s not far from how things used to be done. The name Dundas was given to an Ontario town and Toronto street just because Henry Dundas — the Scottish politician who tried to slow Great Britain’s abolition of the slave trade and apparently never set foot in Canada — was the friend of a lieutenant-governor.

I attended a south Vancouver elementary school that got its name from William Van Horne, who held top posts at the Canadian Pacific Railway, including president, during the transcontinental railway’s final years of construction. We cheered “Van Horne!” on sports days. We received notices with a choo choo train doodle at the top.

Only now do I realize how weird it is that my schoolmates, many of whom were Chinese Canadians like me, shouted this rich guy’s name when so many Chinese workers died and were exploited under his tenure. Still, after spending eight formative years at the school, I can’t help but feel nostalgia when I hear the name.

The writer Robert Jago has also noticed this disconnect, with the names of awful men reduced to “empty sounds” over the decades. Dundas the politician has become largely forgotten, wrote Jago in Canadian Geographic, with the street bearing his name “representing nothing more than a point on a map, a spot to meet or the place to go for authentic Chinese food.”

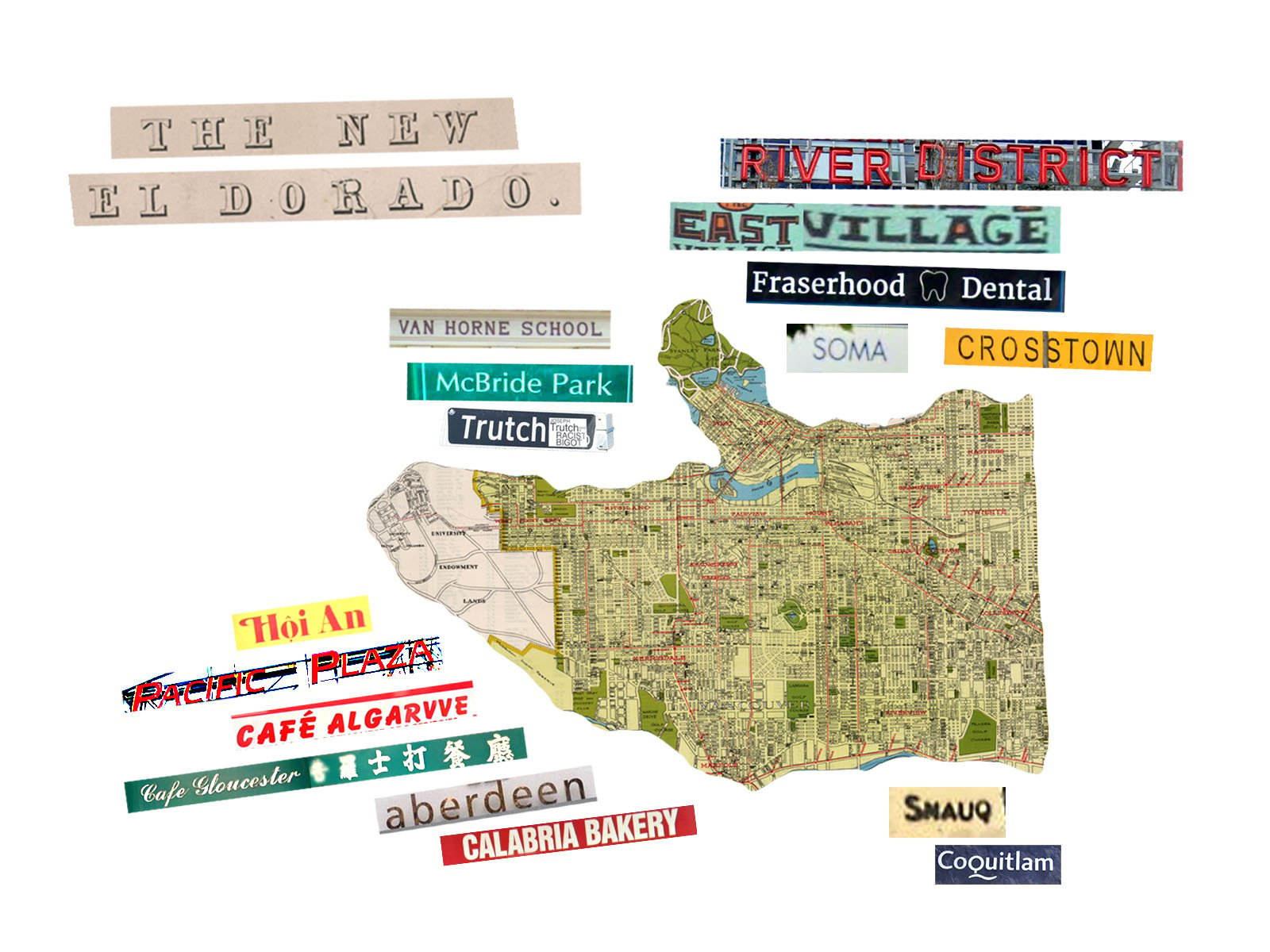

Place names are not just markers of who or what they’re named after, but also markers of time, Jago goes on to say. There’s a local dessert shop called iTofu, capitalizing Apple cool at its height, and A1 Exterminators Bed Bug and Pest Control, from a time when it paid to be at the front of a phone book. Jago offers a helpful lens to reading Vancouver’s young history through what places are called. Is it power that’s behind a name? Prestige? Promise? Or something more personal?

Take the West End and its mid-20th century apartment boom. There are a few building names in tribute to Britain, like King Charles Court, and the nearby beach, like Pacific Sands, but many more with names of women dear to the men who built them. There’s the Sandra, Carmen Manor, Caroline Court and Shelmarjay Apartments, the names of three beloveds rolled into one. There are Spanish names and vaguely Spanish names: Corona, Esticana, El Cid, Casa Del Vandt. There are clusters of towers and walk-up apartments all over the region, and some nod to faraway places: Telkwa Apartments to the village near Smithers, Shaunavon Apartments to the Saskatchewan town, Bel Air to California, Dunure to a Scottish castle. Ultimately, these are personal touches by landlords — dominantly men — who hung on to their buildings as investments.

But condos are different. Condos are built by developers enticing buyers of different tastes. Rather than personal names, these are product names. Some embody this more than others: Opal, Coco, Gold House and Bordeaux, as if buying a condo was like buying jewelry, perfume or wine. The other day I came across an ad for a new development near Langara College called Pure. Curious what that meant, I visited its website, which explained that the homes are designed with “pure intention.”

Interestingly, as names of cruel colonizers are stripped from public assets, colonial names are still being given to private ones. The names of condos on Cambie Street, near Queen Elizabeth Park, have royal gestures — Henry, Lilibet, the Charlotte, Empire. Atkin points out that Queen Elizabeth Park isn’t even named after the current regent, but her mother. As for names like Marquise and Contessa, they carry on the tradition of feminine building names, a step up I suppose from a boomer name like the Sandra. Along with others on the west side called Westbury and Gryphon House, it’s all very Downtown Abbey.

“It boils down to purely marketing, a branding exercise,” said Atkin. “It’s aspirational qualities that sell it out the door, not just to locals, but to an international audience.”

Vancouver’s naming committee might be responsible for public assets, but so much else falls into the hands of economic interests. Aside from private buildings, there’s whole neighbourhoods, with namings and renamings often initiated by real estate marketers and business groups, then hyped by lifestyle publications and boosters of tourism. The less said about the thought behind the Burnaby development called the Amazing Brentwood the better.

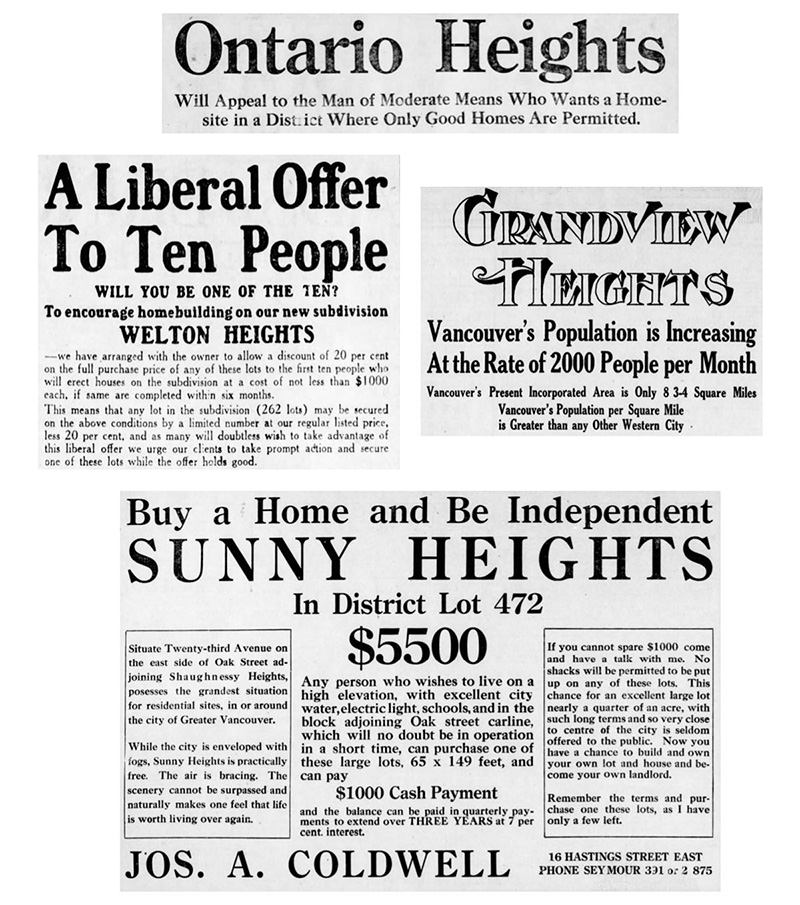

Lofty names, like Renfrew Heights, and pastoral names, like Sunshine Hills, might’ve once been popular, but names that echo hip new frontiers are now in vogue, with a dash of working-class grit that echoes Brooklyn-style gentrification.

Vancouver’s got some new “districts” (River District, Brewery District) and “towns” (Railtown, Port Town). You never know when one might stick. In the early 1990s, Crosstown was used by artists to describe a part of downtown they wanted preserved as creative space. But real estate marketers would later seize the invented name, and in 2018, the school board voted to name a new school in the area Crosstown, cementing its use.

Some attempts at renaming are more left field, piggybacking on existing place names elsewhere in an attempt to capture some of their brand identity. In the late-2000s, developers and tourism marketers tried to rebrand a strip of Main Street as “SoMa” for South Main, even though 80 per cent of Main Street still lay south of it. In 2012, the Hastings North Business Improvement Association tried to rebrand the gentrifying area as the East Village, as if trying to desperately summon the creative energy of New York’s East Village.

Overall, said Atkin, these names “speak to not being comfortable with where you live, always wanting to bring the qualities of another place here.”

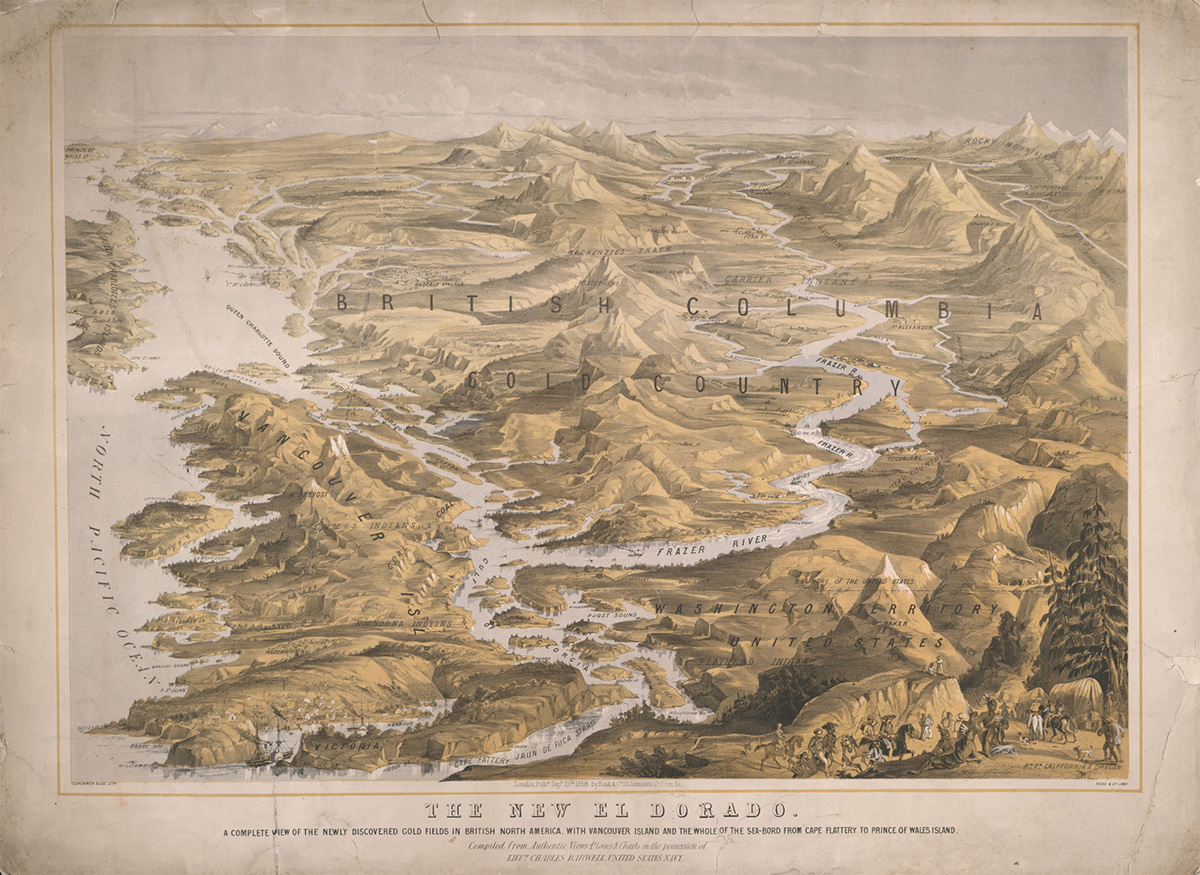

In 1858, Harper’s Weekly called B.C. the New El Dorado for the gold rush. Reading all these uppity new names for condos and communities today, I feel as though we are part of a New New El Dorado, the gold rush of real estate. I suppose putting a price tag on place is a defining feature of a colonial “blip” in the timeline.

When author Ray Bradbury wrote his stories about a colonized Mars, he came up with place names like “New Chicago” and “New New York.” Wherever settlers go, they bring along the names that they know. When the British came to the Lower Mainland, they created another Surrey, a New Westminster and another Mission and Mount Pleasant, like so many other settler communities in North America.

It’s the same with our non-Anglo immigrants, whose businesses have echoes of where they came from. There’s Calabria Bakery, Café Algarve, Pampanga’s Cuisine, Busan Daeji Gukbap. North Richmond in particular has become a miniature Hong Kong, with places named after neighbourhoods and landmarks, even as specific as malls and hotels. There’s a café named Kowloon, a flower shop named Repulse Bay and malls named after the areas of Aberdeen and Admiralty.

But when colonizers named places, there was often erasure. Jago reminds us of the older names in use: Sto:lo, now called the Fraser River; T'lagunna, now called Golden Ears; Kulshan, now called Mount Baker.

The names of Indigenous communities were renamed too for colonial importance and convenience. When the B.C. government restricted the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh people to reserves in the 1870s, the seasonal village of Eslhá7an — on what’s now called North Vancouver — was given the name “Mission Indian Reserve No. 1.” It was the location of St. Paul’s Catholic Church, where an investigation was recently launched to determine what happened to the children who attended the residential school there and never returned home.

Of the government’s numbered reserve names, Squamish Nation Coun. Khelsilem calls it a system that “made sense for their own purposes.”

Colonizers did use some Indigenous names for places, but they were often anglicized, and entered common use in that form. X̱ats'alanexw became Kitsilano, kʷikʷəƛ̓əm became Coquitlam, W̱SÁNEĆ became Saanich.

“These were attempts to ‘honour’ local history, but it was still misappropriation and foreign determination,” said Khelsilem.

In the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh language, places are usually named for descriptions of the land or historic events. Some place names are taken from what neighbouring peoples called them in their languages.

While Khelsilem would like to see historical names for Indigenous places come back into use, he also says that the creation of new names is important.

Edmonton, when renaming its wards, formed a committee of 17 women from Treaty 6, 7 and 8 communities, as well as Métis and Inuit representatives. Earlier this year, each ward received a new Indigenous name, chosen with place in mind. There are descriptive names like Karhiio, Cree for “tall, beautiful forest,” and historic ones like the Inuit Anirniq, which means “breath” or “spirit.” That name came from the 1950s and ’60s when Inuit infected with tuberculosis were flown to Edmonton for treatment, with many dying and later being buried there.

Khelsilem says processes like this show that these are not dead, but living languages.

Closer to home, the Riverview lands in Coquitlam — home to the storied mental health facility — was also renamed by the Kwikwetlem First Nation this year. The kʷikʷəƛ̓əm people have a 9,000-year relationship with the site as a spot for food, medicine, ceremony and, due to its high elevation, a refuge during floods and raids by other communities. The new name is səmiq̓ʷəʔelə, which means Place of the Great Blue Heron. Chief Ed Hall says his own members are learning to pronounce the fresh name.

There are suggestions now that B.C. itself should be renamed, with Jago pointing to “S'ólh Téméxw” as a candidate, which in the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language means “Our World.” There are different theories about how “British Columbia” was chosen back in 1858, from staking out its Britishness in the face of Americans to a colonial secretary calling it an opportunity for the Anglo-Saxon race to do “justice” to Christopher Columbus. Whatever the reason, it was considered clumsy even then. The London Morning Chronicle called it “cumbrous and awkward, attesting to a poverty of invention.”

Big renamings aren’t without precedent in our province. In 2009, the Queen Charlotte Islands were renamed Haida Gwaii, literally “Islands of the Haida People.” In 2010, the Georgia Strait, the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Puget Sound and all connecting channels were renamed the Salish Sea.

Of course, there are always critics who say that stripping colonial-era names in favour of Indigenous ones is erasing history. Khelsilem thinks this is ironic.

“It’s bringing back history that was already there and had been erased,” he said.

Khelsilem shared with me an online map he’s worked on called Squamish Atlas, which shows Sḵwx̱wú7mesh place names and their stories. Many of the places important to his people have become city parks, and he wants to see their names return to common use. Jericho Beach was the village of Iy̓ál̓mexw, which means “good land.” Lumberman’s Arch was the village of X̱wáy̓x̱way, known for celebrations and its 60-metre-long longhouse where many families lived.

The map shows a completely different conceptualization of place than Vancouverites today might be used to, with their vision of a region of roads that funnel into a downtown, roads that bear the names of kings and princes long dead.

The Sḵwx̱wú7mesh map stretches up along the coast into Whistler, with dots of permanent settlements and summer villages in the south, and landmarks with more ageless names than Anglo pioneers. For all those who came after Canada was created, getting to know these names is a start to knowing where we live.

“Places names are an entry point into repatriation,” said Khelsilem. “Visible signs, monuments — they remind people that there’s another history here.” ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: